Sexual violence is a very big social and health issue, it sets up also as a gender and race problem, as it affects mainly girls and black girls; in addition, the crime is committed more than 90% of times by males. Sexual abuse is a harmful, humiliating, and traumatic experience to the physical and mental health of men and women with immediate and late consequences.

A systematic literature search was performed according to guidelines in the PRISMA statement. Searches were conducted in PubMed. Keywords included combinations of the words "sex offenses" and children and Brazil.

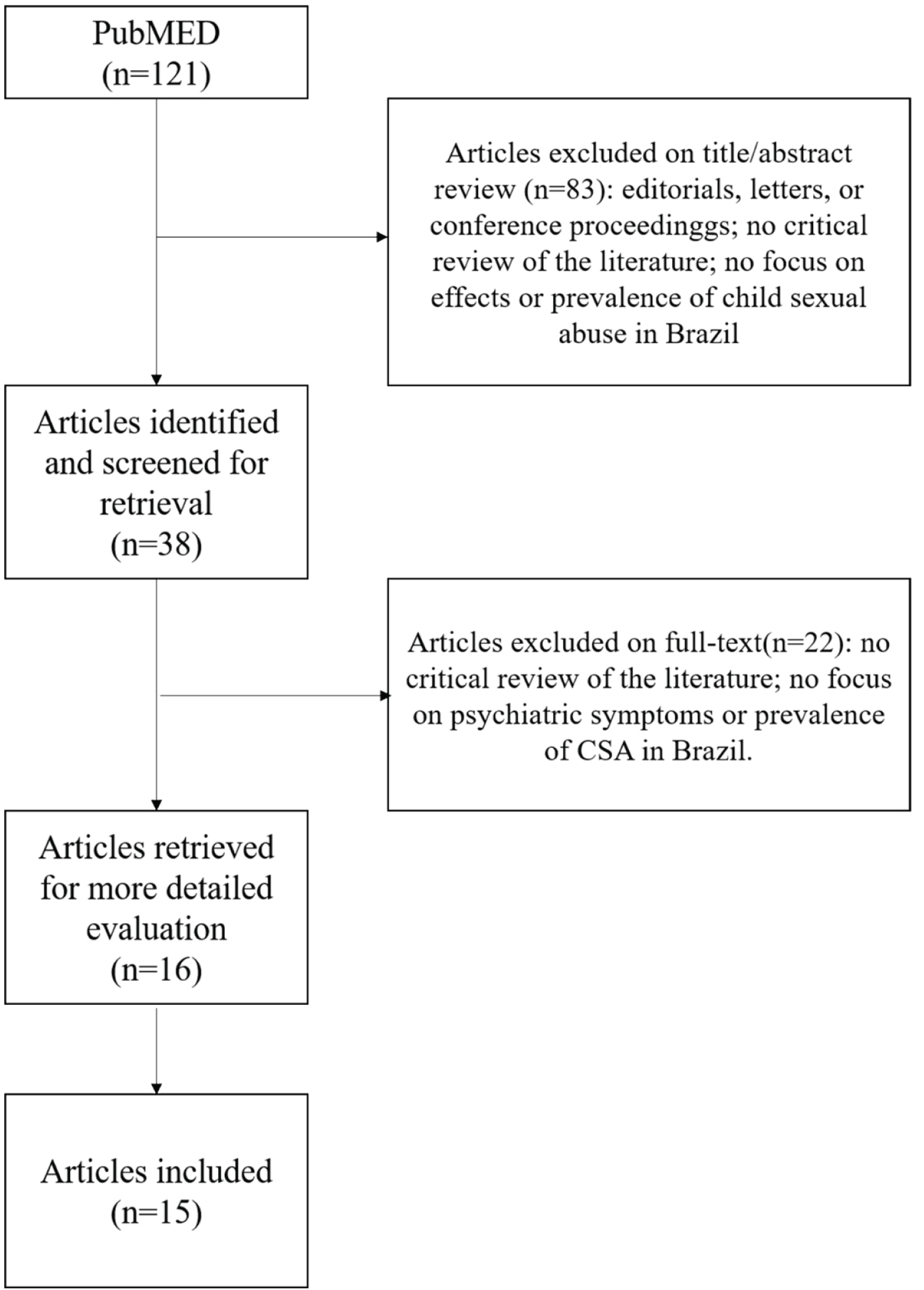

The search strategy yielded 121 hits in PubMed, after applying exclusion and inclusion criteria, and after manual selection were retrieved 15 publications.

Machismo is still a very big social problem. It affects all social spheres of most of the Latin-American countries. Due to this matter, we can explain the underreporting of CSA in boys. The low notification of sexual violence against men is partly due to the toxic masculinity.

More studies are needed, so health professionals, teachers and especially families can recognize early signs of CSA, besides that, public policies need to be implemented urgently in order to reduce these egregious cases.

Childhood, Violence, Psychological repercussions, Children victims of sexual abuse

Sexual violence is an enormous social and health issue. It is a difficult crime to investigate as well as to prove it, mainly when its victims are children and adolescents. Most of the time, the victims feel ashamed and embarrassed of denouncing this kind of tragedy. This creates an unfavorable scenario and increases the difficulty to help the victims and their families with their multiple pains, including the physical as well as the emotional harms [1]. Child Sex Abuse (CSA) sets up also as a gender and race problem, because it affects mainly girls and black girls; in addition, the crime is committed more than 90% of times by males [2-8].

Every day, thousands of children are abused in places that were supposed to be safe. Several studies show that the most common places where this kind of crime occurs were at home and school, not to mention that such atrocity is perpetrated by those who are close to the victim [1,3,4,6,7,9].

Sexual abuse is a harmful, humiliating, and traumatic experience to the physical and mental health of men and women with immediate and late consequences. When it comes to immediate repercussions victims usually experience suicidal thoughts, mental disturbs, behavioral disturb, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [10], and regarding the late consequences, they stumble upon senile depression, and high risk of suicide in elder individuals [11]. Thus, the aim of this study was to analyze the psychiatric and psychological repercussion of children and adolescents, victims of CSA in Brazil.

A systematic literature search was performed according to guidelines in the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement. Searches were conducted in PubMed. Keywords included combinations of the words "sex offenses" and children and Brazil.

Studies were considered if they were published between January 2015 and September 2020 and appeared in peer-reviewed, English, Portuguese, and Spanish language journals. Further articles were identified by a manual search of reference lists from retrieved papers. Studies were included if they: (i) Appeared in peer-reviewed journals; (ii) Were published in full; (iii) Were not dissertation papers, editorials, letters, conference proceedings, books, and book chapters; (iv) Had primary and sufficient data derived from longitudinal, cross-sectional, case-control, or cohort studies. For the aim of this systematic review, only reviews that investigated prevalence, psychiatric symptoms or disorders following CSA in Brazil were included.

The search strategy yielded 121 hits in PubMed. Titles and/or abstracts of these records were screened, and 84 did not meet eligibility criteria. Out of the remaining 38 full-text articles, 22 were excluded for various reasons. Thus, our systematic review includes 15 publications (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram.

View Figure 1

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram.

View Figure 1

Table 1: Description and results of the included reviews. View Table 1

As it is known, Child Sex Abuse (CSA) is a difficult crime to investigate and prove. Children and adolescents' dependence on their parents aggravate the problem, once victims usually take too long to report the crime, and when this occurs, it is still difficult to find physical evidence to confirm the rape. It is important to remember that parents generally have no knowledge regarding the abuse, and when they notice it, they fear about the consequences of notification [1].

Despite this, according to Gaspar & Pereira [12] from 2009 to 2013 there was an increase on the number of notifications of CSA. Sexual abuse notification tripled, due to a real increase in the number of cases, to greater awareness of the victims and/or health professionals, or even to better structuring and the number of reporting units. It is clearly observed that girls are the most affected. In almost all the studies, the number of girls who suffered a sexual abuse was bigger than the number of boys [2-8].

Machismo is still -in the 21st century- a very big social problem. It affects all social spheres of most of the Latin-American countries which could explain the underreporting of CSA in boys. The low notification of sexual violence against men is partially due to the toxic masculinity. Men fear having their virility questioned, which leads them not to seeking for health services after having suffered sexual violence [12]. Machismo perpetuates a mistaken conviction that men who are victims of violence tend to homosexuality. This stereotype causes a delay on reporting the abuse. As a result of this delay, they may experience more severe CSA over time [8]. No one believes that boys may be victims of CSA which decreases the visibility of these cases. In the familiar context, the possibility that boys may suffer unbelief and even physical punishment after reportion, shows how difficult it is to individuals to understand that boys may be victims of CSA. In the social context, these cases are permeated by misconceptions regarding gender identity or sexual orientation of the victim, contributing to a lesser visibility of male sexual abuse as a public health problem [13]. Besides that, da Silva & Roncalli [2] affirm that men tend to have less access to health services when compared to women. Although a tremendous amount of men suffers this type of violence, women are still the main victims in all age groups whichcharacterizes a marked gender violence [12].

The socioeconomic conditions of families are a risk predictor for CSA. Significantly higher rates of sexual violence were observed among black-skinned students from public schools, children of mothers with low levels of education, students who did not live with their mother and/or father, and among those who were already working and receiving retribution for that. Associated and protective factors as for the occurrence of CSA included attending to a private school, being son of a highly educated mother, living with the mother and/or father and having family supervision [5].

Victim's residence was alarmingly the most frequent place of abuse, and the aggressors were mostly men who in most of the cases were known by the victims. Even scarier than this, only the fact that the own children's parents were the most common perpetrators [3,4,10]. The violations generally occurred in situations understood as affection, when the aggressor and the child were alone. The moments of play, a characteristic activity of childhood, were favorable situations for adults to practice sexual violence. The aggressors took advantage of childhood situations such as playing to perpetrate the crime. Thus, the victims cannot immediately recognize the violence, which prevents the aggressors from being reported [3]. Home, which should be a place of protection and care, has become a place of violence and child victimization.

A curious contradiction exists in the literature as to the safety of children at school. While some studies show that the number of cases of CSA within educational institutions is increasing [9] others describe schools as a protective factor for CSA [8].

Regarding the types of sexual violence, the following were identified: Rape, sexual harassment, indecent exposure, sexual exploitation, child pornography and others. It was observed that, among the types of sexual violence, rape was the most frequent, possibly related to the fact that other types of sexual violence are not recognized as violence. It seems to be more difficult for children to define harassment, indecency, pornography and other types of violence, which makes complaints and/or explanation of the facts difficult [8].

According to Silva & Barroso-Junior [6], in a study realized from January of 2008 and December of 2009 in the city of Salvador, the most common findings in children bodies were anogenital lesions, hymen ruptured in 82.7% of confirmed cases in girls. There were signs of recent abuse such as hematomas, drops of blood and edema in 30% in which the hymen was ruptured. Two girls of this study, both aged 11, were already pregnant and despite abortion being authorized by law in cases of sexual abuse, there are still a lot of girls who have to carry on with an undesired pregnancy, this because legal abortion in Brazil, has become a religious and moral debate.

It is well known that children who have been sexually abused suffer the negative effects of this throughout their lives. The most common manifestations are inadequate school performance, psychological problems (depression, anxiety, suicide attempt and post-traumatic stress disorder) and personal relationships [3]. Among the immediate consequences, the impact of CSA on the mental health of the victims stands out, according to Platt, et al. [10] From all analyzed children in their study, four of them (1%) attempted suicide; five (1.3%) developed mental disorder; 90 (22.4%) showed behavioral disorders; and 77 (20.0%) had PTSD. CSA also was related positively to another psychiatric traumas, violence perpetrated by a relative during pregnancy and fear of the childbirth, for those victims had to carry on with the pregnancy [14].

Sexual violence was more frequent among students who reported insomnia, feeling alone and having no friends. This type of violence was more reported among school children with risky behaviors, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, drug experimentation and early sexual life. The chances of suffering sexual violence were greater for students who felt insecure on the way between the school and their home and at the school itself, as well as those who reported having suffered bullying [5]. Agreeing with this idea, Fontes, et al. [15] found that abused young people were more likely to use illicit drugs, alcohol and have friends who already did. Sexually abused students appear to be less likely to continue their studies in high school and graduation and are more likely to be already working. The victims of sexual violence avoid staying at home and try to spend as much time as possible outside their house to feel more secure. Insomnia can be explained by the presence of nightmares, fears and mood disorders such as depression. The lack of friends and loneliness can be associated with aggressive behaviors or the withdrawal from the creation of new social bonds, as well as characteristics of low self-esteem and bullying.

Finally, Gomes Jardim, et al. [11] claims that all childhood maltreatment types were significantly associated with the risk of suicide, and an emphasis is placed on sexual abuse, which, unlike other mistreatment subtypes, is more strongly associated with the risk of suicide in the elderly.

CSA is a rarely notified crime, due to this, it is necessary to learn how to identify behaviors that the victims show, in order to be able to act in a precocious way and prevent more serious consequences of this crime. It is necessary to create strategies that can minimize physical and psychological damage than children and adolescents may suffer immediately or belatedly. Children and teenagers represent the future of our countries, the hope that there are better days coming. It is extremely important to remember the importance of preserving their lives and their futures, for which we must take action now. Literature clearly shows us the various and different forms of psychic suffering that abused children suffer. In order to save the future of children and adolescents we must first save their present.

We call for attention from government authorities around the world, as we find that social inequality, poverty, a general lack of education has a direct impact on the lives of children. Without saying that, the religious polarization, surrounding governmental decisions and important debates such as abortion, is being harming and will continue to harm the future of more young people. More studies are needed, so health professionals, teachers and especially families can recognize early signs of CSA, besides that, public policies need to be implemented urgently in order to reduce these egregious cases.