We describe the clinical cases of two pediatric patients who were treated with a total maxillectomy and chemo/radiotherapy for suffering from malignant tumors of the maxilla.

The reconstruction of the floor of the orbit was done with titanium micromesh and the defect in the maxilla and hard palate was reconstructed with free flaps.

This allowed a quick swallowing rehabilitation and an excellent cosmetic result.

Total maxillectomy, Children, Free flap, Malignant tumors

Total maxillectomy is a surgical technique that involves the resection of all the bony walls of the maxilla.

Its main indication is the treatment of malignant tumors of the maxillary sinus or neoplasms originating in neighboring regions and extending to the maxilla.

Resection of the upper and lower wall requires reconstruction so that the patient does not have significant functional alterations.

In children, the indication for this technique is infrequent and it occurs within prior or postoperative chemo and radiotherapy schemes to treat malignant tumors of the maxillary sinus.

The clinical cases of two children who were treated by a total maxillectomy for malignant tumors of the maxilla are described.

Male patient, 13-years-old.

He consulted for a left facial tumor and pain in the gingiva of the upper jaw.

On examination, facial asymmetry and bulging of the left hemipalate were observed, and rhinoscopy revealed a tumor occupying the ipsilateral nostril.

By Computed Tomography (CT) of paranasal sinuses, a tumor occupying the left maxillary sinus was diagnosed, eroding the floor of the orbit and the bone of the sinus floor with extension to the pterygomaxillary fossa and nasal fossa.

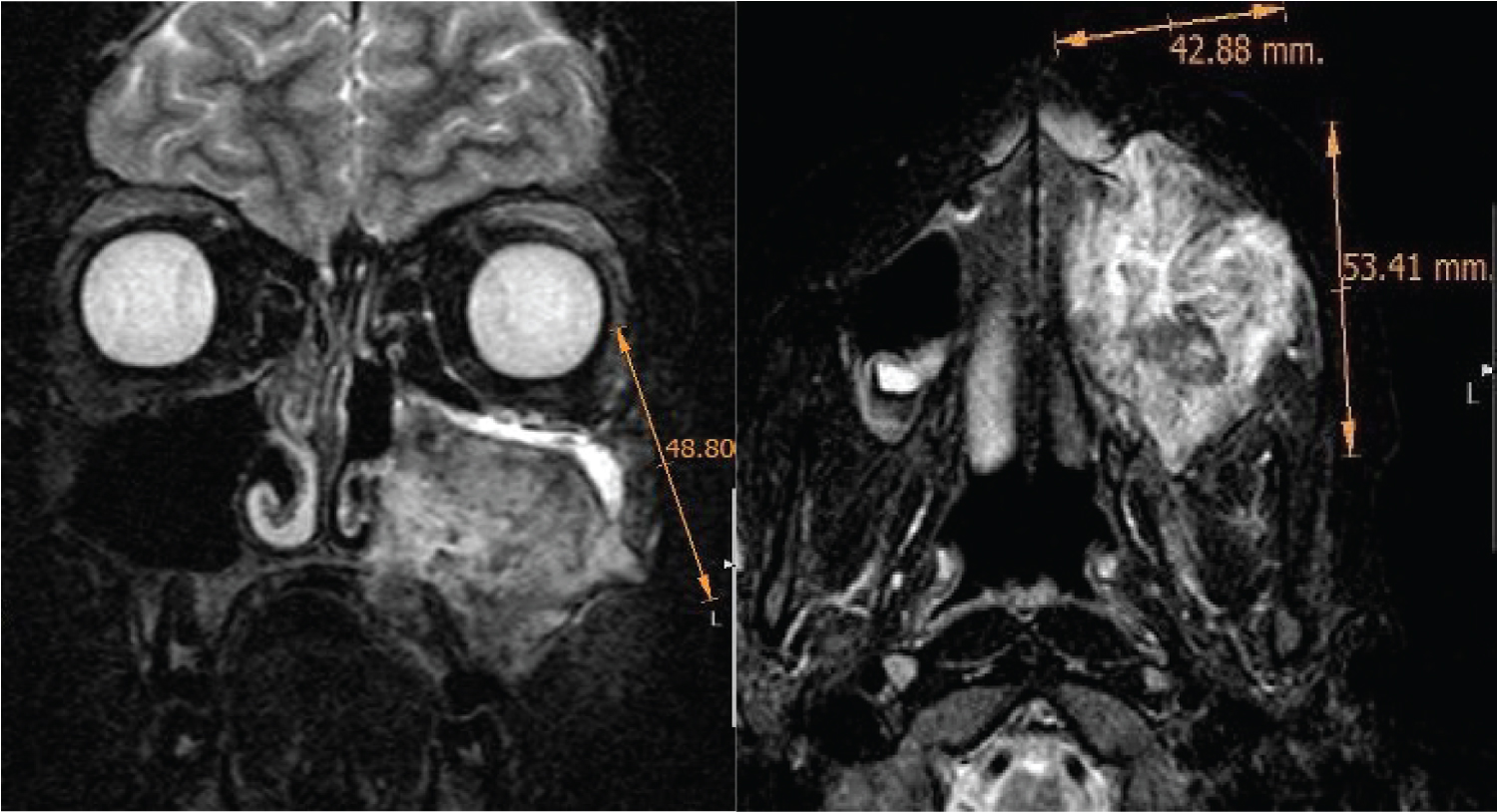

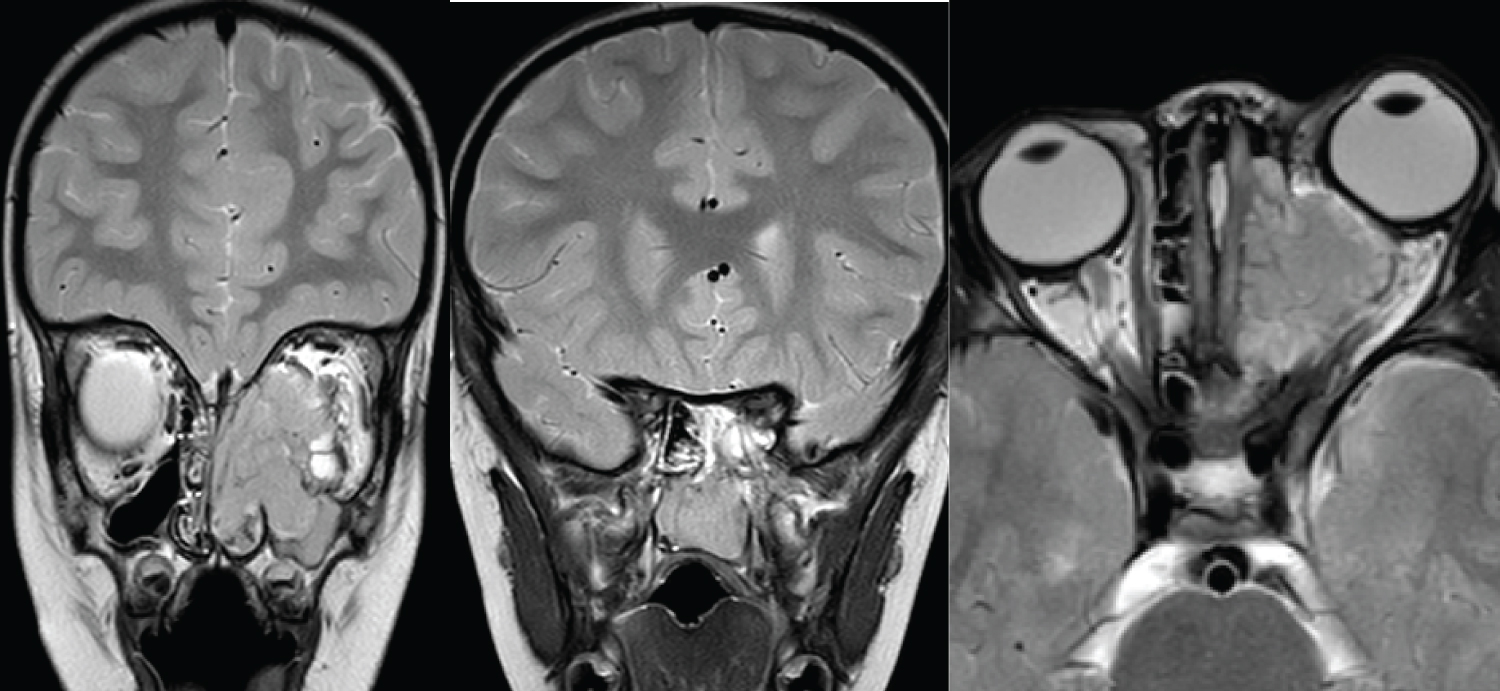

The Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) with contrast revealed a neoplasm occupying the left maxillary sinus, which was enhanced with the contrast and eroded all the walls of the maxillary sinus, without compromising the facial skin (Figure 1).

Figure 1: MRI: Undifferentiated sarcoma with erosion of the bone walls of the maxilla and extension to the pterygomaxillary fossa.

View Figure 1

Figure 1: MRI: Undifferentiated sarcoma with erosion of the bone walls of the maxilla and extension to the pterygomaxillary fossa.

View Figure 1

Distant extension was not detected by chest and abdominal tomography and bone scintigraphy.

A biopsy was done under general anesthesia by endonasal approach with endoscopes.

Histopathological diagnosis and with immunostaining techniques was undifferentiated round cell sarcoma.

He underwent three cycles of chemotherapy with ifosfamide, mesna, vincristine, actinomycin, and doxorubicin with marked reduction in tumor size.

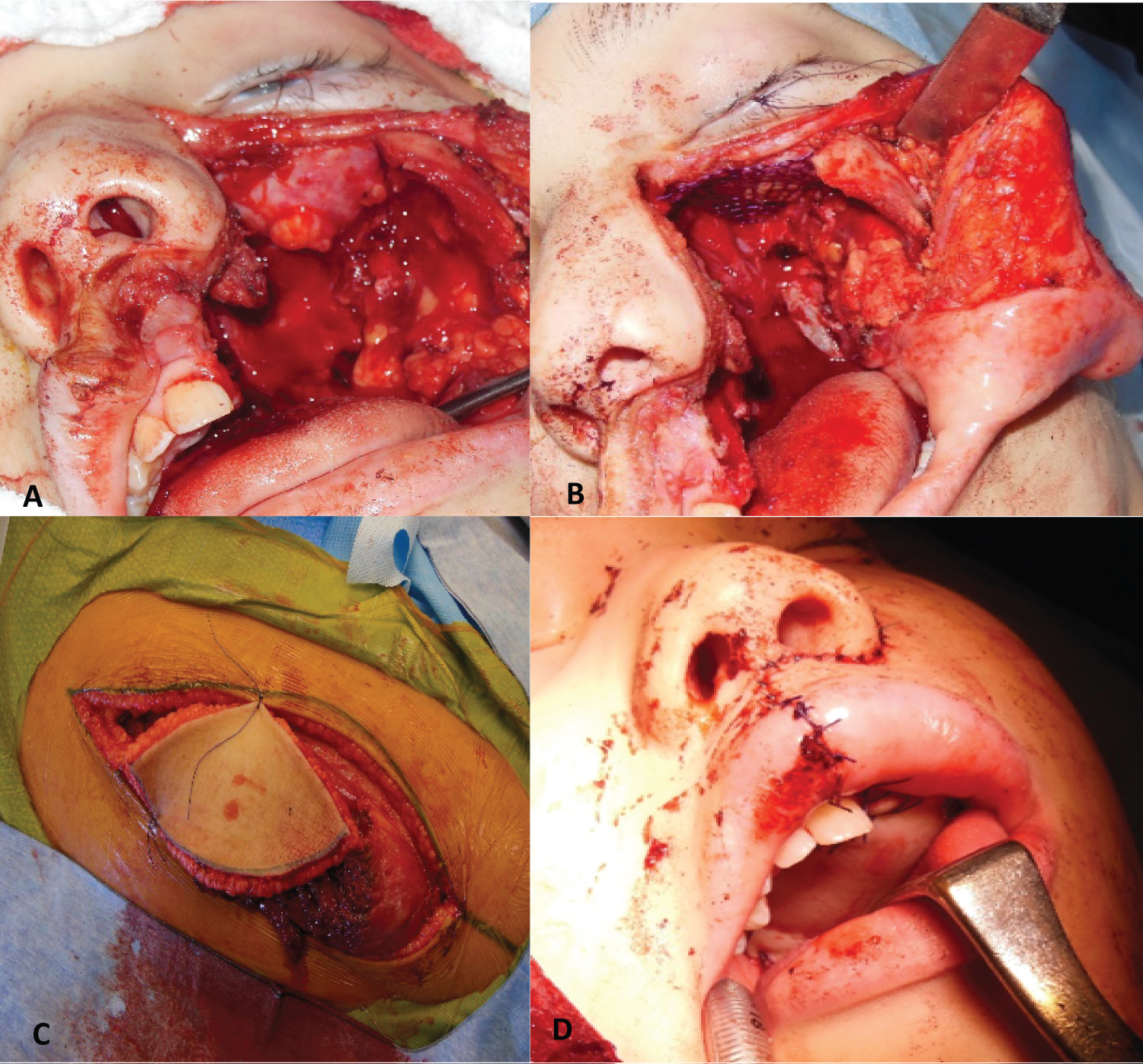

A total maxillectomy was performed and the floor of the orbit was reconstructed with a titanium micromesh and the left hemipalate defect with a fasciocutaneous free flap from the anterolateral region of the thigh (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Total maxillectomy (A) Post-maxillectomy defect (B) Orbit floor reconstruction with titanium mesh (C) Dissection of the fasciocutaneous free flap from the anterolateral region of the thigh (D) Oral view of the flap reconstructing the left hard hemipalate.

View Figure 2

Figure 2: Total maxillectomy (A) Post-maxillectomy defect (B) Orbit floor reconstruction with titanium mesh (C) Dissection of the fasciocutaneous free flap from the anterolateral region of the thigh (D) Oral view of the flap reconstructing the left hard hemipalate.

View Figure 2

The margins were free and the histological diagnosis was undifferentiated round cell sarcoma with 99% necrosis.

He performed postoperative chemotherapy, completed 9 cycles.

10 months later, had a recurrence for which radiotherapy and surgery was indicated.

The flap and the plate were extracted and part of the malar and zygoma were excised and the defect was reconstructed with a free flap of the rectus abdominis.

He continued with several cycles of chemotherapy with etoposide + carboplatin.

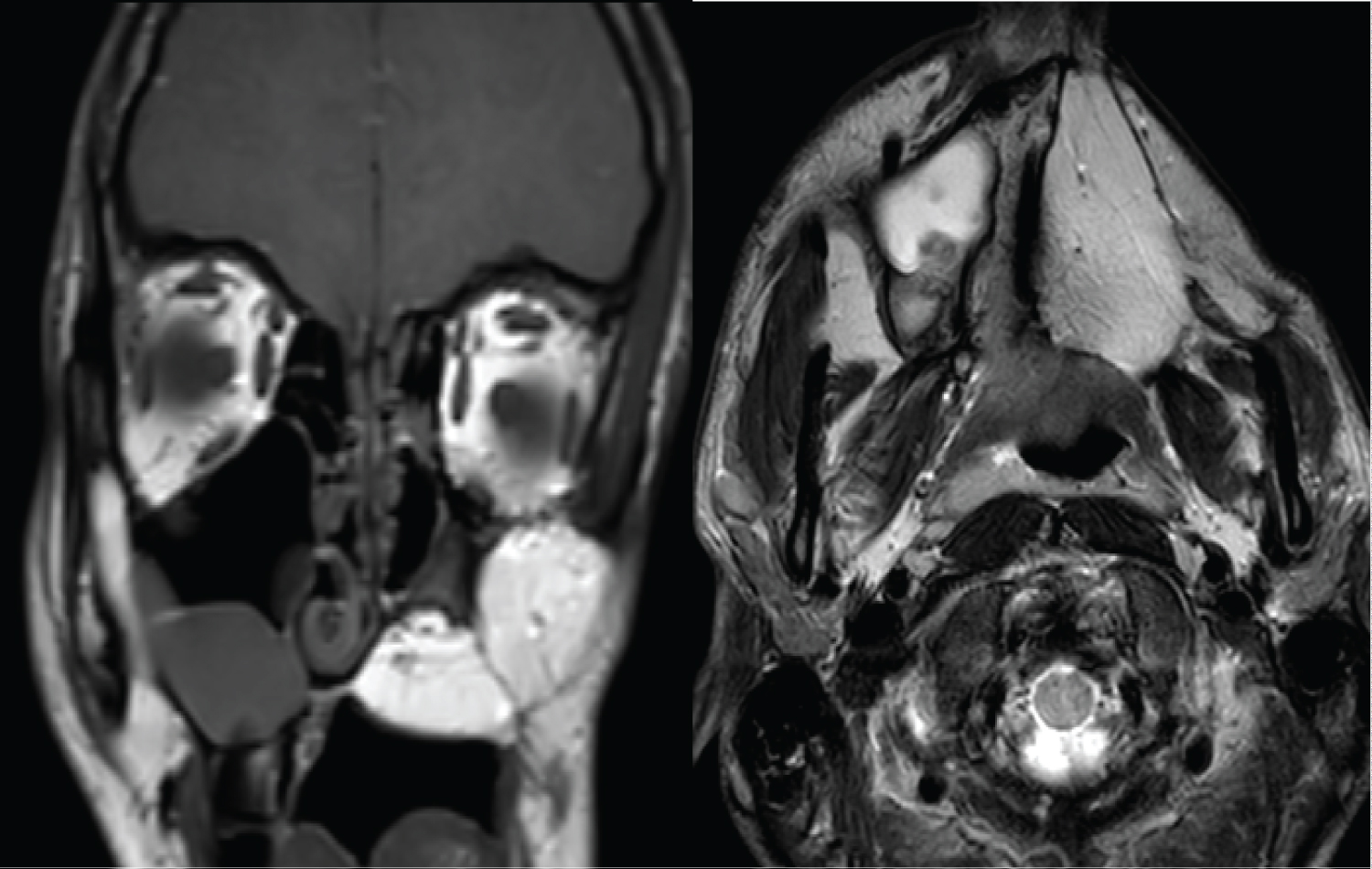

7 years later he is disease free (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Postoperative MRI: The flap of the anterolateral region of the thigh is observed, reconstructing the maxillary defect.

View Figure 3

Figure 3: Postoperative MRI: The flap of the anterolateral region of the thigh is observed, reconstructing the maxillary defect.

View Figure 3

4-year-old male patient.

He consulted for left mucous rhinorrhea and left exophthalmos.

Rhinoscopy revealed a tumor in the left nostril.

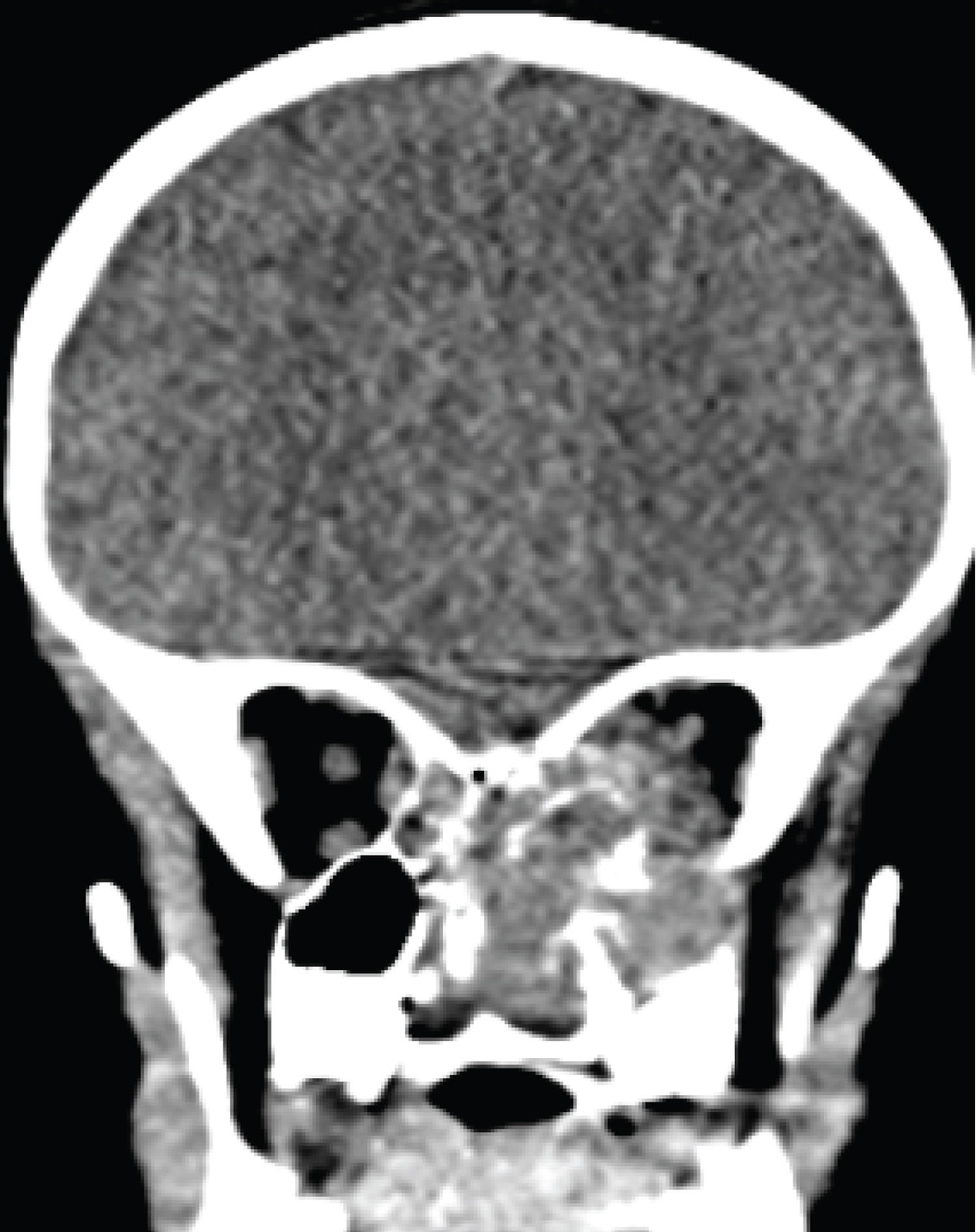

By CT a tumor in the nasal fossa was diagnosed with extension to the maxillary sinus, ethmoid and left orbit, with destruction of its medial and inferior wall (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Computed tomography: Maxilla rhabdomyosarcoma with bone destruction.

View Figure 4

Figure 4: Computed tomography: Maxilla rhabdomyosarcoma with bone destruction.

View Figure 4

By contrast MRI, a heterogeneous neoplasm centered in the nostril with extension to the orbit, with invasion of the extra and intraconal space, the nasopharynx and the pterygomaxillary fossa was seen (Figure 5).

Figure 5: MRI: Maxillary tumor with extension to the nasal cavity, ethmoid, rhinopharynx and orbit.

View Figure 5

Figure 5: MRI: Maxillary tumor with extension to the nasal cavity, ethmoid, rhinopharynx and orbit.

View Figure 5

Positron emission tomography diagnosed an increase in metabolism located only in the midface region (SUV: 3.6).

An endonasal biopsy with endoscopes and debulking of the tumor was performed under general anesthesia.

The histopathological and immunostaining report was embryonal-type rhabdomyosarcoma.

He did five cycles of chemotherapy with ifosfamide (3g, m2/day) for 2 days, mesna (3g, m2/day) for 3 days, vincristine (1.5 mg, m2/day) for 3 days, and actinomycin (1.5 mg/m2/day) for 1 day.

Post-chemotherapy CT and MRI showed a significant reduction in tumor size (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Post-chemotherapy computed tomography: significant tumor shrinkage is observed.

View Figure 6

Figure 6: Post-chemotherapy computed tomography: significant tumor shrinkage is observed.

View Figure 6

PET-CT showed a significant reduction in metabolism at the tumor level (SUV: 2.5), without metabolic activity elsewhere.

A total maxillectomy was performed through a Weber-Ferguson incision, and endonasally with endoscopes. The remaining tumor in the ethmoid was resected and the periorbit was partially dissected and resected.

The reconstruction of the orbital floor was done with a titanium micromesh, and the palate defect was reconstructed with a free fascio-cutaneous flap from the anterolateral region of the thigh.

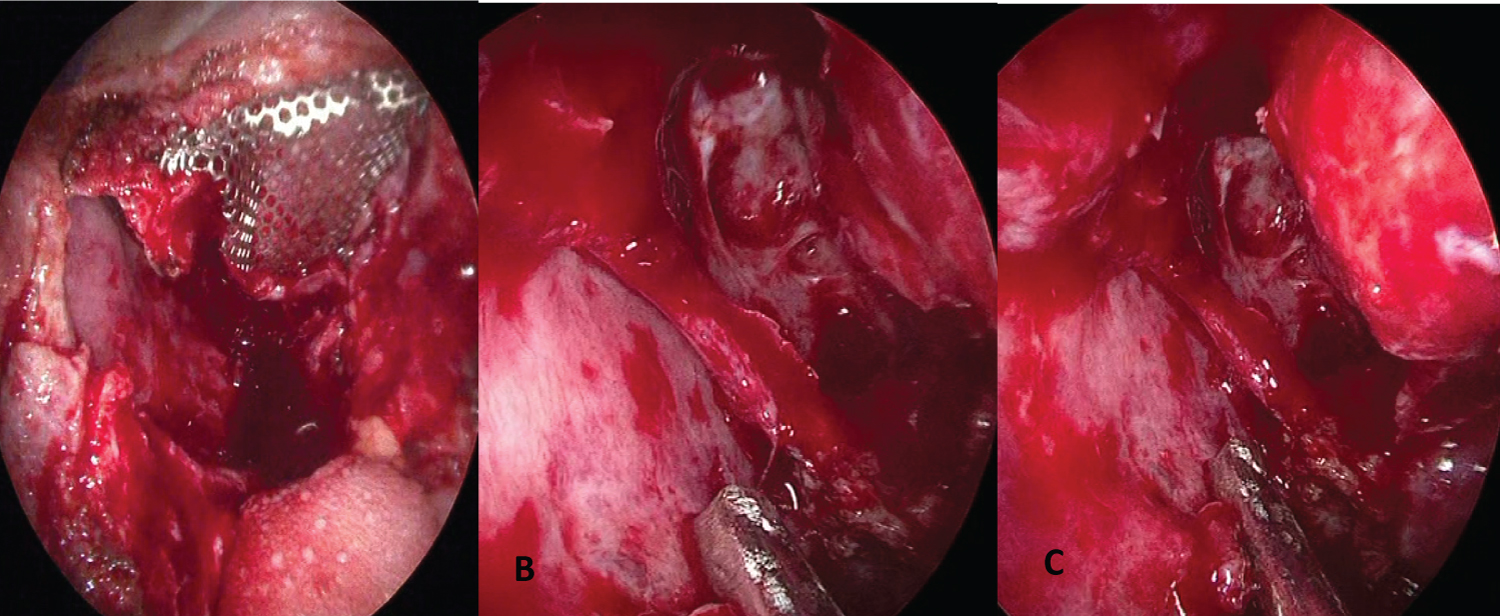

The recipient vessels were the facial artery and vein, and an end-to-end microsurgical anastomosis was performed with the flap vessels (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Endoscopic view (A) Reconstruction of the orbital floor with titanium micromesh; (B) Anterior and posterior ethmoidectomy, sphenoidotomy and middle turbinate resection (C) Orbital fat within the nasal cavity after resection of the periorbit.

View Figure 7

Figure 7: Endoscopic view (A) Reconstruction of the orbital floor with titanium micromesh; (B) Anterior and posterior ethmoidectomy, sphenoidotomy and middle turbinate resection (C) Orbital fat within the nasal cavity after resection of the periorbit.

View Figure 7

The freezing biopsies of the margins were negative, except in the periorbit that was partially resected, exposing the orbital fat.

The histopathological report of the surgical specimen was: effects of chemotherapy neoadjuvant on the mucosa of the maxillary sinus and bone with little residual tumor (7%).

He had a good evolution and was discharged from hospital at 12 days (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Post-operative computed tomography: micromesh is observed reconstructing the floor of the orbit, and the free flap filling the facial defect and reconstructing the hard hemipalate.

View Figure 8

Figure 8: Post-operative computed tomography: micromesh is observed reconstructing the floor of the orbit, and the free flap filling the facial defect and reconstructing the hard hemipalate.

View Figure 8

Treatment with postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy was indicated according to the rhabdomyosarcoma treatment protocol.

Controls with a follow-up of 1 year did not detect disease.

Spiro, et al. [1] classified the type of maxillectomy according to the bone walls included in the resection.

They call a limited maxillectomy that which involves the resection of a wall, more frequently the medial or the inferior wall, subtotal the one that includes at least two walls and the total one in which all the bony walls of the upper jaw are resected.

Total maxillectomy is a rare indication in children.

The surgical technique is similar to that used in adults, and reconstruction of the defect caused by maxillectomy is always necessary to improve function and aesthetic results.

In adults, filling the defect with a prosthesis that is prepared preoperatively and placed at the end of the surgery allows the patient to feed orally early, and is an option especially in elderly patients and with tumors that have a poor prognosis.

Preoperative preparation of the obturator, removal of the temporary prosthesis, and fabrication of the definitive one requires multiple procedures that can be poorly tolerated by pediatric patients.

In one study [2] they preserved the mucoperiosteum of the hemipalate and upper gingiva from the central incisor to the last molar and after performing the maxillectomy they sutured both flaps, closing the oral defect after total maxillectomy. They reinforced this closure with buccal fat and temporal muscle, to reduce the possibility of an oronasal fistula.

This type of reconstruction would be contraindicated in tumors that erode the floor of the maxilla.

Another important aspect is the reconstruction of the floor of the orbit, which prevents the eye from descending and being included in the field of radiotherapy, in addition to avoiding complications such as diplopia, globe malposition, enophthalmos and hypophthalmos.

Reconstruction of this sector can be done with a temporal muscle flap, a temporal muscle flap with coronoid process, septal mucoperichondrium or with a titanium micromesh covered inferiorly by mucoperiosteum or muscle (temporal, free flap).

The use of free flaps such as the anterolateral thigh makes it possible to reconstruct the defect in the same surgical time and allows the rapid rehabilitation of the patient.

We believe that it is the best option to reconstruct the post-maxillectomy defect in children.

It allows filling the space left by the resection of the maxilla avoiding sinking of the face, covering the titanium mesh with muscle and filling the defect in the palate, allowing rapid oral feeding.

Other free flaps described for the reconstruction of this sector are the radial and the anterior rectus.

In the post-growth age, the fibula free flap allows the bone reconstruction of the defect and the possibility of placing dental implants to achieve better function.

The disadvantages of reconstruction with free flaps are the longer surgery time, although the work of two teams simultaneously shortens the times (in the 2 pediatric cases described, the average surgery time was 6 hours), the longer hospitalization time and the possibility of a greater number and severity of complications.

In a study [3] that included 72 patients between 7 and 77 years of age, who had a reconstruction with an anterolateral free flap of the thigh after a total maxillectomy, 6 complications were described (4 serious and 2 minor: 8.33%).

In another study [4] they reported a necrosis rate of 3% among 1212 myocutaneous free flaps from the anterolateral sector of the thigh used to reconstruct oral and maxillofacial defects.

In a study carried out at the Anderson Cancer Center [5] they compared the functional results and the delay in the detection of recurrences in patients who had a maxillectomy with rehabilitation using an obturator (n = 73) or a reconstruction with a free flap (n = 40).

The quality of speech and swallowing were comparable in the two groups except in patients who had palatal resections greater than 50%, where reconstruction with free flaps was better.

The average time to detect recurrences was similar in the two groups.

The use of endoscopes during maxillectomy may be useful to guide the osteotomy at the level of the pterygoid process, to dissect the periorbit of the maxillary superior bone wall and especially to perform resections of the papyracea lamina, and medial periorbit in cases of infiltration and to perform an ethmoidectomy, sphenoidotomy, and resect limited extensions in the pterygomaxillary fossa and rhinopharynx [6].

Total maxillectomy is a surgical technique infrequently indicated in children due to its significant morbidity and the aesthetic impact it produce in pediatric patients.

In cases of malignant tumors, it can be indicated within multimodal therapeutic schemes.

Reconstruction of the defect with microsurgical flaps allows rapid swallowing rehabilitation and produces a very good cosmetic result.

It is the best option for our group to reconstruct the total postmaxillectomy defect.

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

The authors received no specific funding for this work.