Background: Length of hospital stay, complication and mortality are the primary outcomes that should be measured during diabetic ketoacidosis management. However, data associated with the length of stay, complications, and mortality rate due to diabetic ketoacidosis remains limited in Ethiopia. In addition, nonfiction is very scarce about factors associated with treatment outcomes starting from its initial presentation and the overall management process. Therefore, this study was aimed to assess the treatment outcomes of children admitted with diabetic ketoacidosis at the Felege Hiwot comprehensive referral hospital, North West, Ethiopia.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted among children admitted with diabetic keto acidosis between 2016 and 2021. Data were collected using the data abstruction tool. Then, stored in Epi-dataversion 4.6 and exported into STATA 14.0 statistical software for analysis. Catagorical variables were described using proportions and compared using the Chi-squre test; Whereas, continuous parametric variables with median and standard deviations were compared using parametric(t-test). Model goodness of fit and assumptions were checked. The association between independent variables and length of hospital stay was assessed using binary logistic regression. Finally, variables with p-value < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Result: The median length of hospital stay was 8 ± 6.2 days. 59.3% of the patients had along hospital stay (> 7 days). The majority of patients (97.5%) improved and were discharged with 14.2% complications and 4(2.5%) died in the hospital. Factors that affected longer hospital stay were Residence (aOR = 4.31; 95CI = 1.25-14.80), family history of diabetes (aOR = 0.12; 95% CI = 0.02-0.64), glycemia at addmision (aOR =1.01; 95% CI = 1.00-1.02), insulin skipping (aOR = 0.08; 95% CI = 0.01-0.98), abdominal pain (aOR = 4.28; 95% CI = 1.11-15.52) and time in which the patient get out of diabetic ketoacidosis (aOR = 6.39; 95% CI = 1.09-37.50).

Conclusion: Majority of patients showed improvement and were discharged to their homes after a long hospital stay and with a very low mortality rate followed by complications (14.2%). The time in which the majority of patients got out of diabetic ketoacidosis were between 24-48 hours. Thus, to achieve intended treatment outcome early in time, clinicians and other stakeholders should focus on diabetic ketoacidosis presentation and precipitating factors with possible multicenter studies.

Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus, Diabetic Ketoacidosis, Treatment outcome, Children, Ethiopia

ADA: American Diabetic Association; BGM: Blood Glucose Monitoring; BMI: Body Mass Index; CIRI: Continuous Intravenous Regular Insulin; DKA: Diabetic Keto Acidosis; ESPE: European Society for Pediatric Endocrinology; FBS: Fasting Blood Glucose; HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus; IDF: International Diabetic Federation; IVF: Intravenous Fluid; ISPAD: International Society of pediatrics and Adolescent Diabetes; NCDs: Non-Communicable Disease; RBS: Random Blood Glucose; SSA: Sub Saharan Africa; T1DM: Type one Diabetes Militus; TLC: Total Leukocyte Count; TB: Tuberculosis

Type 1 diabetus militus (T1DM) is the most common endocrine metabolic disorder in children; TDM is a serious, chronic and progressive disease that occurs when the pancreas does not produce enough insulin [1]. Almost one in 300 children develop T1DM [2]. These findings have been documented in many countries including both developed and developing countries [2,3]. It has been reported that, the incedence of T1DM is increasing by 3-4% per year globally in light of geographical variation with a high correlation between this incedence and socio-economic factors [4,5].

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is an expensive acute complication of T1DM that can occur when there is a comparative or complete decrease in circulating insulins [6]. The magnitude of DKA among children with diabetes has increased over the past 3 decades [7]. DKA has become the most common sticky situation of T1DM in children with an incidence of 1-10% per year and 30 to 70% prevalence in both high and middle-income countries [7-9]. It is the most common reason for hospitalization, morbidity and mortality in children with an admission rate of 16.5-78% in hospitals [10]. The pooled mortality for DKA is estimated to the range of 2-5% in developed nation and 6-24% in developing countries [11-14].

The prevalence of DKA at the time of diagnosis in sub-Saharan Africa is between 70% and 80% [15]. The proportion of children diagnosed with DKA in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, was high (35.8%) [10]. Likewise, in Gojjam, Ethiopia, the overall incidence rate of DKA was 2.27 per 100 children/month of observation [16].

Insulin difficiency, dehydration and hormone increments such as cortisol, adrenaline, glucagon, and growth hormone are some of the clinical features of children admitted with DKA [17]. The biochemical criteria for the diagnosis of DKA are hyperglycemia (blood glucose leve l > 200 mg/dl,venous pH less than 7.3 or serum bicarbonate level less than 15 mEq/L and ketonemia (blood b-hydroxybutyrate concentration++ 3 mmol/L) or moderate or severe ketonuria [6,18,19].

Patients can be dramatically ill, and the severity of presentation can be graded based on the degree of acidosis; Mild DKA: venous pH form 7.2-7.3 or serum bicarbonate < 15 mmol/L; Moderate DKA: venous pH form 7.1-7.2 or serum bicarbonate < 10 mmol/L; Sever DKA: venous pH < 7.1 or serum bicarbonate < 5 mmol/L [19]. And as severity increases, the need for pediatrics intensive care as well as the risk of morbidity and mortality increases [20]. However, with proper management, most patients recover rapidly [7].

It has been identified that, poor glycemic control, comorbidities, younger age, and low socio-economic status have been associated with an increased risk of developing DKA; but, it is unclear if this risk factor influences patient outcomes in pediatric management centers [21].

Higher mortality rates among children admitted with DKA were reported with an increased incidence of cerebral edema, sepsis, shock, cerebral injury, altered levels of consciousness, respiratory failure with hyposphotemia, renal failure, and delayed diagnosis both in developed and developing countries [11,14,22-26]. DKA could be the principal source of death, mainly when complicated by cerebral edema/injury with an estimated mortality rate of 20 to 50%, and 15-35% of survivors are left with permanent neurologic deficits [12,27,28]. Acute complications of DKA can be also accompanied by malnutrition, parasitic infections, and microbial infections with tuberculosis and HIV [28]. Overlapping of these conditions contributes to the increased morbidity and mortality rates. The inability of patients to afford insulin treatment leads to poor glycemic control. As a result, patients may seek alternative treatment from traditional healers or use herbal remedies further complicating the management process [29].

During DKA treatment, the administration of insulin hinders the production of ketoacidosis and facilitates it’s metabolism, thereby helping correct the acidosis [17]. Effective treatment requires the replacement of insulin, fluids, and electrolytes. Applying the novel approach of early diagnosis and treatment by multidisciplinary diabetic care teams can also ensure good outcomes [24,30-32]. Length of stay, complications, and overall mortality among children with DKA during management are the foremost outcomes that should be measured. This is because, it is highly trusted to improve T1DM and DKA-management related complications. However, data associated with length of stay, complications following management, and rate of mortality due to DKA remain limited in Ethiopia.

Therefore, the current study aimed to determine treatment outcomes of children admitted with DKA at Felege Hiwot comprehensive referral hospital in Amhara region, Northwest, Ethiopia.

The study was conducted in the Bahir Dar city; placed 565 Km far from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia, in Amhara region, Northwest Ethiopia., has two public referral hospitals, one primary hospital, ten health centers, and four private hospitals. This study was conducted at Felege Hiwot’s comprehensive specialized referral hospital (FHCSH). This hospital is expected to serve more than 10 million people from the catchment area. This hospital currently has a total of 1431 manpower in each discipline with 500 formal beds, 11 wards, and 39 clinical and nonclinical departments/units/providing Diagnostic, curative, Rehabilitation, and preventive services both in outpatient & inpatient bases.

Apart from other services, the hospital provides diabetic treatment services by nurse practitioners, pediatric residents, and pediatricians. The study period addressed from 1 st January, 2016 to February 30 /2021.

An institution-based retrospective cross-sectional study was employed.

Source population: All pediatric T1DM patients who were on follow-up at Felege Hiwot comprehensive referral hospital were the source of population in this study.

Study population: All pediatric T1DM patients who were admitted with DKA during the study period.

Randomly selected Pediatric cases (< 15-years-old) T1DM clients admitted with DKA in the period from January 1 st 2016 to February 30, 2021 (5-years) were included. To determine the sample size, the following assumptions were considered: 80.95% of clients were discharged with an improvement in Jimma with a 95% confidence level and 5% marginal error [12]. The sample size was calculated using Raosoft software (http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html). Because the total population is < 10,000, we used the correction formula. Yields the final sample size 176.

The study participants were selected from the registration book. The medical profiles of children admitted with DKA between January 1 st , 2016, and February 30, 2021, were selected. Finally, cards that fulfilled the criteria were reviewed.

Inclusion criteria: Children aged less than 15 years and diagnosed with DKA from January 1/2016 to February 30/2021 were included.

Exclusion criteria: Children’s charts that had incomplete information and were lost during the study period.

Dependent variables: Length of stay, complication, and mortality of children admitted with DKA.

Independent variables: Socio-demographic (age, sex, residence, and educational status of the children including weight and height); diabetes-related variables/clinical and biochemical variables (family history of T1DM, type of T1DM, the severity of DKA, admission blood glucose readings, duration of chief complaint, sign and symptoms of client presentation, comorbidities, all vital signs, DKA precipitating factors, frequency of DKA episode during the study period, electrolyte disturbance, ketone, and urine glucose level and treatment related - variables and/or medication-related variables (co-medication and a therapeutic class of co-medication).

Operational definitions

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA): Is defined as an admission of blood glucose > 250 mg/dl and the presence of ketonemia and/or ketonuria [6,18,19].

Hyperglycemia: Is defined as a random plasma glucose level > 200 mg/dl and hypoglycemia is defined as a blood glucose level ≤ 70 mg/dl [20].

Euglycemia: Is defined as serum glucose between 100 and 200 mg/dl [33].

Normoglycemia: Is defined as a blood glucose level between 90 mg/dl and 130 mg/dl [19].

A longer hospital stay: Was defined as a hospital stay for > 7 days and a short hospital stay was considered if the patient could stay in the hospital for ≤ 7 days [34].

Poor glycemic control: Blood glucose level for age group (5-12): < 80 or > 180 mg/dl; And for age group (13-18 years) < 90 or > 130 mg/dl and HbA1c > 7.5% irrespective of their age category [1,19].

Treatment outcome: The length of hospital stay, complications following treatment, and mortality of DKA were the measures of treatment outcome in the context of the present study.

Definitions of terms

Chief complaint: This was the main reason for the patient to visit the hospital.

Co-morbidity: Implies concomitant diseases that are not the complications of T1DM and/or DKA.

Co-medication: Co-medications are concurrent drugs prescribed for the treatment of diseases, or deficiencies, other than antihyperglycemics.

Diabetic ketoacidosis: Implies patients with positive urine and/or serum ketones and with plasma glucose greater than 250 mg/dl.

Category of DKA [35]

Mild DKA : Urine and/or serum ketone positive with plasma glucose > 250 mg/dl, arterial pH 7.25-7.30, and an alert level of consciousness.

Moderate DKA : Urine and/or serum ketone positive with plasma glucose > 250 mg/dl, arterial pH 7.0-7.24 with an alert or drowsy level of consciousness.

Sever DKA : Urine and/or serum ketone positive with plasma glucose > 250 mg/dl, venous pH less than 7 with stupor or coma.

Insulin defaulters: Are known type one diabetes patient who discontinued insulin treatment because of different reasons.

Client characteristics: Implies different clinical characteristics and biochemical finding of the patients.

Medical records of patients with DKA admitted to the hospital were drawn from patient logbooks and a card room. The selections of medical records for sampling were based on the physician’s confirmed diagnosis on patient logbooks. Participants included in the study were all TDM patients with DKA admitted to Felege Hiwot comprehensive referral hospital with age < 15-years-old and whose medical records confined compliant client data.

The data were collected by trained data collectors using structured and pre-tested data extraction tools. Data were collected on patient’s demographics, presenting symptoms, precipitating causes of DKA, vital signs, biochemical profiles (admission blood glucose, admission urine ketone, urine glucose) at presentation to the inpatient department, time from presentation to the resolution of urine ketones, length of hospitalization and treatment outcomes.

Data were entered into Epidata version 4.6 software for cleaning and exported to STATA version 14.0 for analysis. Tables and text were used to present the findings. Categorical variables were described using proportions, and continuous parametric variables with median and standard deviation. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square test and fisher's exact test, whereas, continuous variables were compared using parametric (t-test). Binary logistic regression was done to determine the factors that affect length of hospital stay and mortality.

One hundred seventy-six (176) medical records were reviewed; of which, fourteen (7.95%) patient’s charts were not included in the study due to important variables being missing there. Accordingly, 162 patients medical record were investigated with 92.05% of response rate.

The median age of the study participants was 8 ± 4.7 with 2.4 years mean duration of diabetes. And almost 48.8% of them were within the age range of 11-14 years.

Greater than half of the patients were males (51.2%) and the majority of the patients (66.7%) were from rural areas. (Table 1).

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics among T1DM children admitted with DKA, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia, 2021 (n = 162). View Table 1

Out of the investigated patients, 129(80.6%) were newly diagnosed cases and the remaining 31(19.4%) were known T1DM patients. The majority (103[63.6%]) of the patients were on mixed insulin (regular and lent) treatment and the other patients were on either regular and NPH (30[18.6%]) or NPH alone (29[17.9%]) with an average insulin dose of 16.5 ± 10.7 u/day. Greater than half of the patients had T1DM for more than three years (86[53.1%]).And many of the patients had a history of comorbid illness (108[66.7%]) (Table 2).

Table 2: Clinical characteristics among T1DM children admitted with DKA, Bahir Dar, 2021 (n = 162). View Table 2

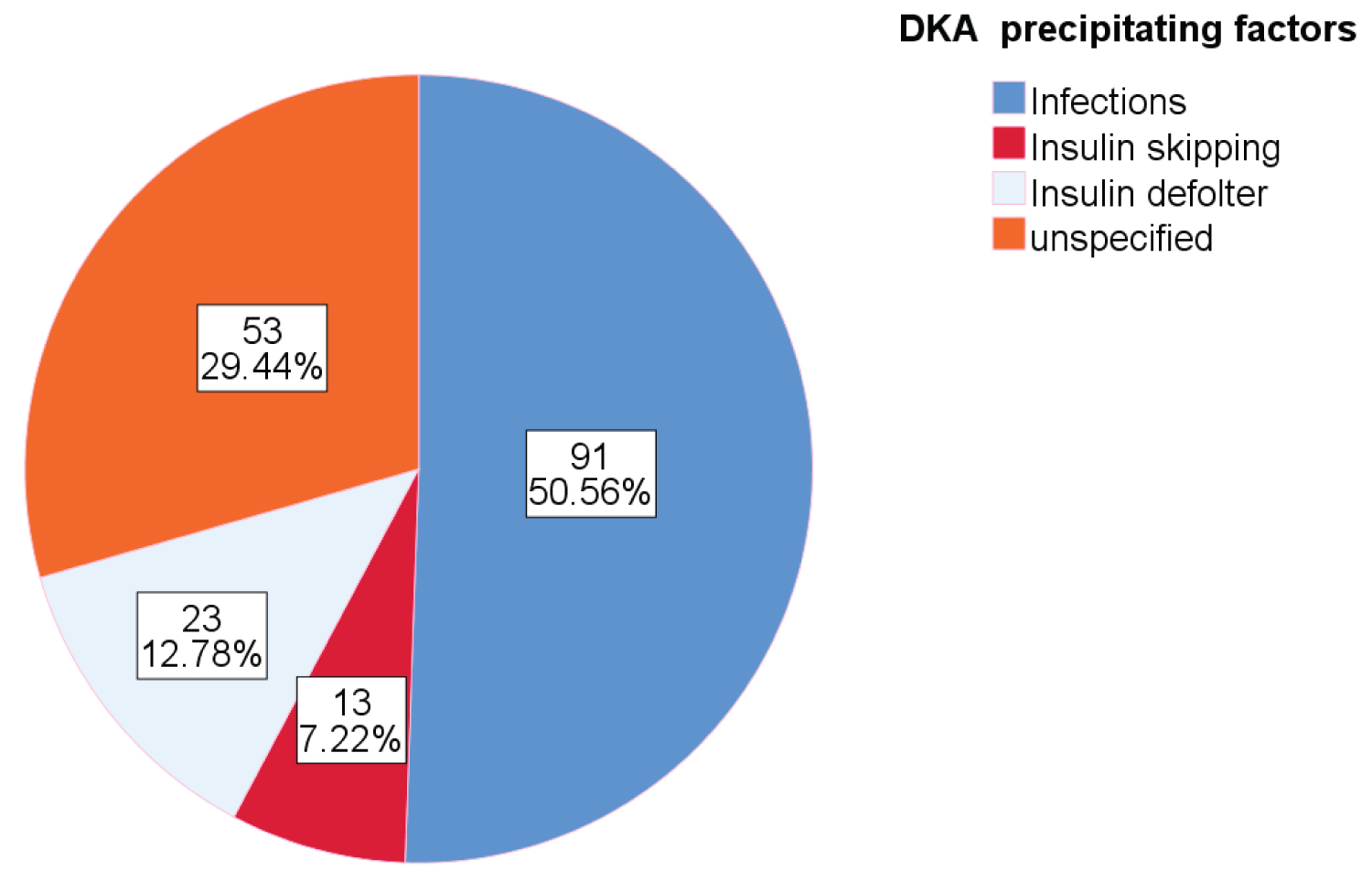

The rate of DKA reoccurrence was assessed and showed that, majority of the patients encountered on it at once (116[71.6%]), 31[19.1%] had two episodes, 12[7.4%] and 3[1.9%] of the patients had three and four episodes of DKA recurrence during their follow up period respectively. And 29(17.9%) of the patients were on severe DKA, whereas 61(37.7%) and 72(44.4%) of the patients had moderate and mild DKA during their presentation. The most common precipitating factor was found to be infection (91[56.2%]).Other precipitating factors are shown in Figure 1 and Table 3).

Figure 1: Precipitating factors of DKA among T1DM children admitted with DKA, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia 2021 (n = 162).

View Figure 1

Figure 1: Precipitating factors of DKA among T1DM children admitted with DKA, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia 2021 (n = 162).

View Figure 1

Table 3: Frequency of DKA episode, severity, precipitating factors, clinical presentation and Laboratory results among T1DM children admitted with DKA, Bahir Dar, 2021(n = 162). View Table 3

In this study, most of the patients were presented with polyuria (144[88.9%]) and polydipsia (137[84.6%]). In addition to these, nausea/vomiting (63[38.9%]), polyphagia (61[37.7%]) and abdominal pain (51[31.5%]) were reported. Regarding vital signs, the mean value of pulse rate was 115 ± 22.1 beats/min, respiration rate was 31.1 ± 10.3 breath/min, and body temperature was 36.6 ± 0.9 °C. Table 3 shows the details regarding clinical presentation and some laboratory results.

In this study, the most commonly used type of fluid bolus was found to be 0.9% normal saline/NS 0.9% normal saline (161[99.4%]) with an average volume of 362.2 ± 348.4 mililiters. Maintenance fluid was carried out mostly with normal saline (0.9%NS) and D5W (75[46.3%]). The average rate of fluids in the majority of the patient was 89 ± 14 ml/hour. Regular insulin was the only insulin drug administered to all DKA patients with an average rate of 9.6 ± 4.3u every 2-4 hours and then every 6 hours, till the patients were free from ketone (start standing dose). However, only 56(34.6%) of the patients were repeated with potassium chloride with 68% of concomitant drug use, mainly antibiotics (73%) (Table 4).

Table 4: DKA management protocol, comedications and treatment outcome among T1DM children admitted with DKA, Bahir Dar, 2021 (n = 162). View Table 4

The majority of patients were free from/got out of DKA between 24 and 48 hours (58[35.8%]). More than three-quarters of the patients (139[85.8%]) did not develop any type of complication; However, hypokalemia (11[6.8%]) and hyponatremia (5[3.1%]) were found to be the most common complication followed by a neurologic sequel and hypernatremia both accounting four cases (4[2.5%]), 4[2.5%]).

The median time stayed in hospital was 8 ± 6.2 days; Where, majority of patients (96[59.3%]) stayed in the hospital for more than the expected duration (> 7 days). Concerning the overall treatment outcome, only (4[2.5%]) patients died; whereas the other patients (158[97.5%]) revealed improvement and discharged to their homes (Table 4).

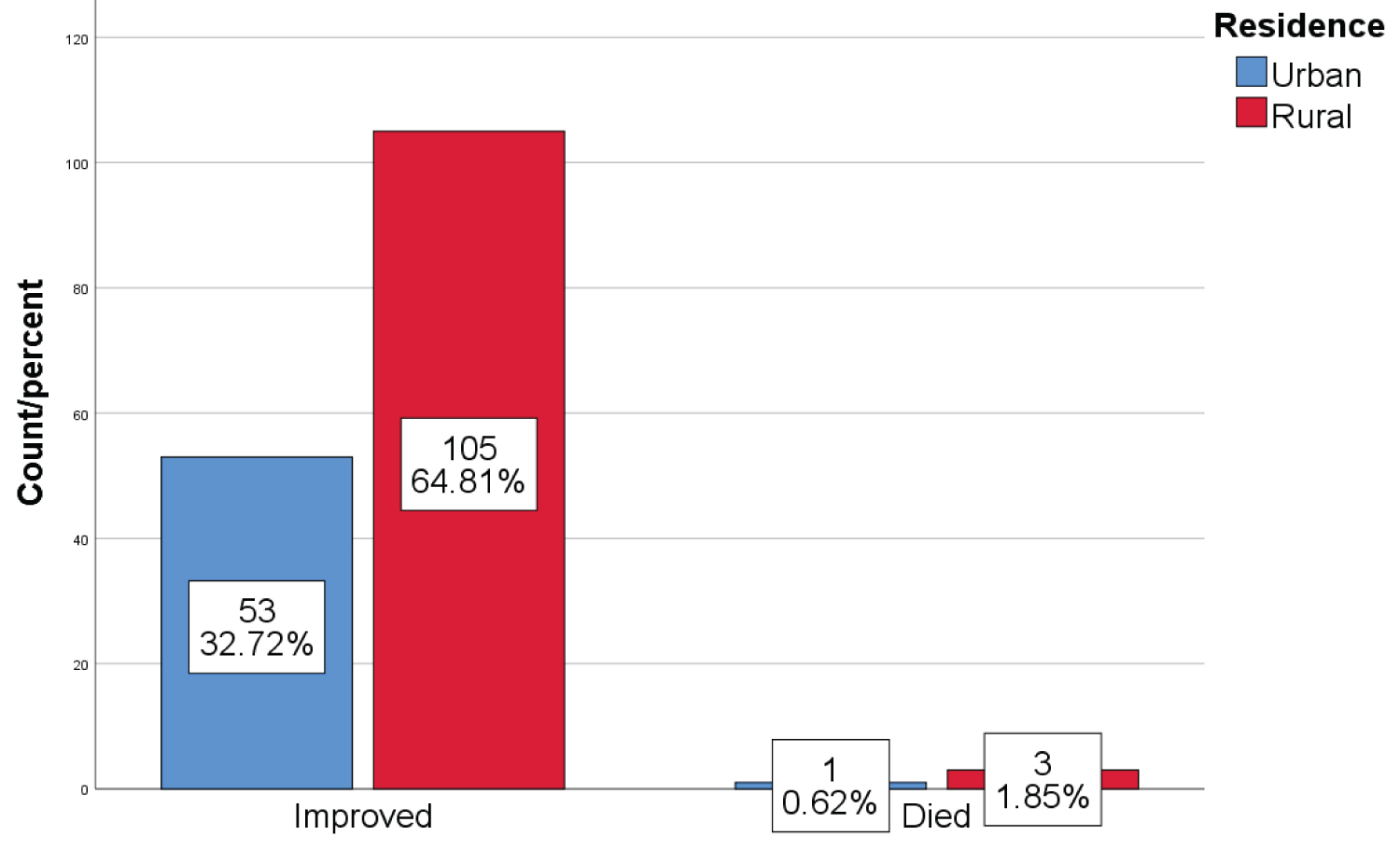

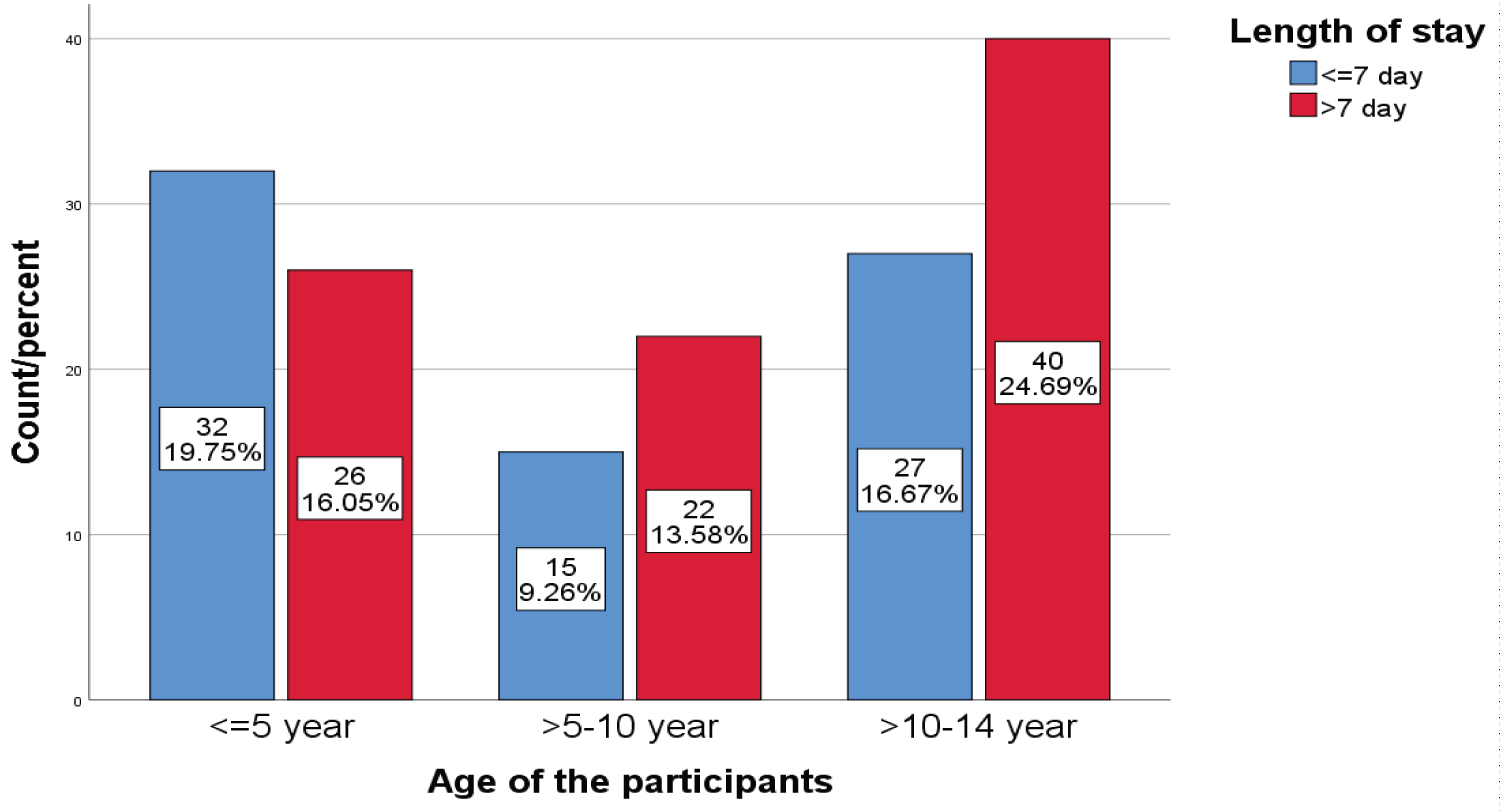

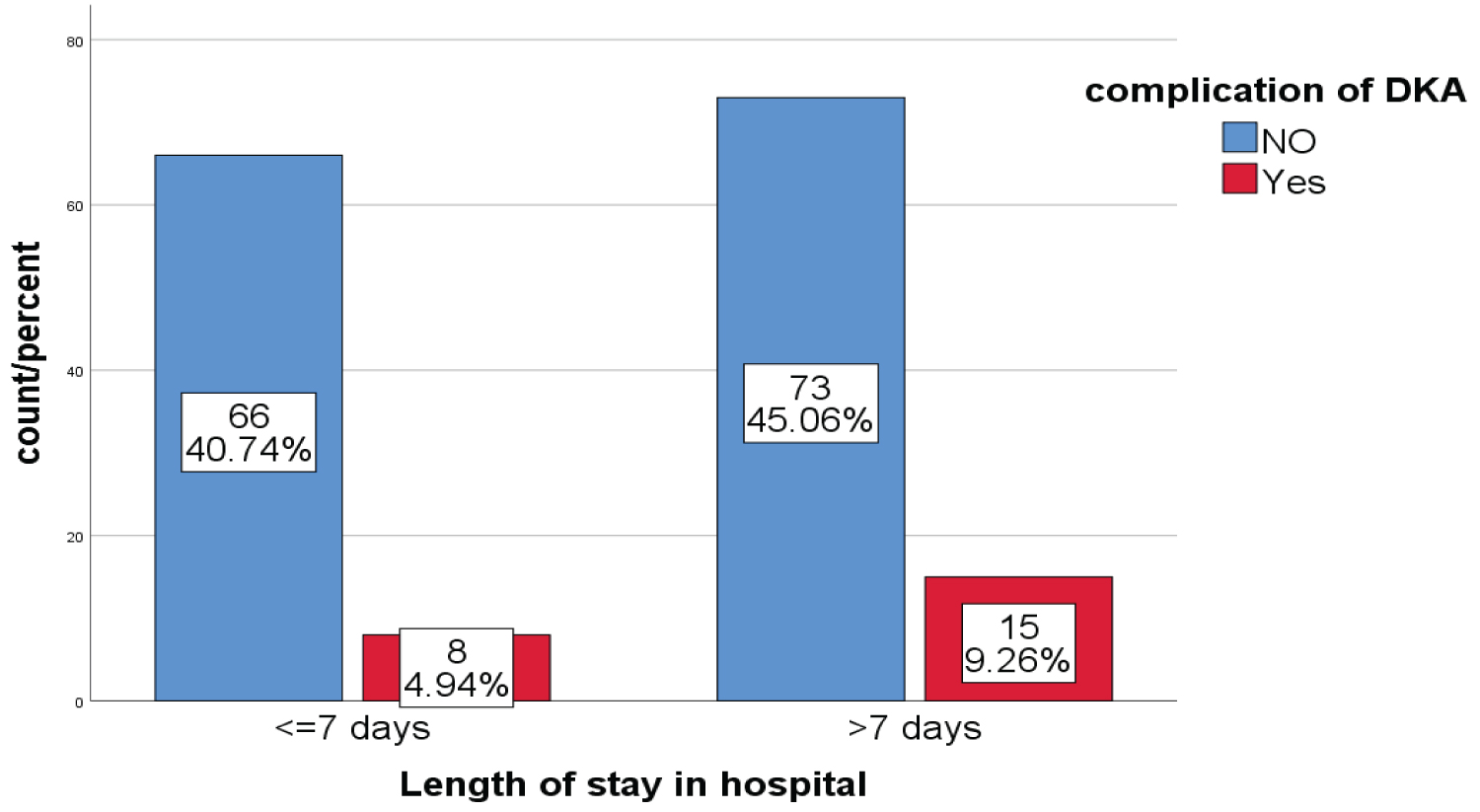

Overall, treatment outcomes including length of stay, treatment associated-complications, and mortality in relation to other variables among T1DM children admitted with DKA, Bahir Dar, 2021(n = 162) showed in the perspectives figure and Table below (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Table 4).

Figure 2: Overall treatment outcome in relation to residence among T1DM children admitted with DKA, Bahir Dar, 2021 (n = 162).

View Figure 2

Figure 2: Overall treatment outcome in relation to residence among T1DM children admitted with DKA, Bahir Dar, 2021 (n = 162).

View Figure 2

Figure 3: Proportion of patients stayed in the hospital in relation to age category among T1DM children admitted with DKA, Bahir Dar, 2021 (n = 162).

View Figure 3

Figure 3: Proportion of patients stayed in the hospital in relation to age category among T1DM children admitted with DKA, Bahir Dar, 2021 (n = 162).

View Figure 3

Figure 4: Proportion of patients who developed complication in relation to length of stay among T1DM children admitted with DKA, Bahir Dar, 2021(n = 162).

View Figure 4

Figure 4: Proportion of patients who developed complication in relation to length of stay among T1DM children admitted with DKA, Bahir Dar, 2021(n = 162).

View Figure 4

The independent variables such as age, residence, client educational status, BMI, duration of chief complaint, family history of T1DM, frequency of DKA episode during the study period, the severity of DKA, DKA precipitating factors, the clinical presentation of DKA like polydipsia, abdominal pain, cough and confusion, location of admission, glycemia at admission, body temperature, having a history of comorbidity such as UTI, URTI, fungal infection, Comedication, time in which the patient get out of DKA and management complication were significantly associated with long hospital stay at the pointless than 0.25 level of significance from the bivariable analysis.

However, residence, family history of T1DM, glycemia at admission, DKA precipitating factors, DKA presentation with abdominal pain, location of admission, and time in which the patients could get out of DKA were found to be significantly associated with long hospital stay in the multivariable logistic regression model less than 5% level of significance.

The existence of interactions among independent factors was checked but there was no significant interaction.

Consequently, after adjusting other covariates, the odds of longer hospital stay among the rural resident patients were greater by 31% as compared with the urban resident group of the patients (aOR = 4.31, 95% CI = 1.25-14.80, p-value = 0.020).

Likewise, DKA presentations with abdominal pain among patients were associated with longer hospital stay by 28% compared to patients with no abdominal pain (aOR = 4.28, 95% CI = 1.11-15.52, p-value = 0.035). Which means, the time of improvement/recovery time from DKA and to be discharged from hospital among patients with abdominal pain was significantly longer compared with patients with no abdominal pain during their presentation.

Furthermore, those patients who get out of DKA after 72 hours had more likely to be stayed in the hospital by 6.39 times as compared to patients who get out of DKA for less than 24 hours (aOR = 6.39, 95% CI = 1.09-37.50, p-value = 0.040).

However, patients with DKA precipitated by the omission of insulin had less likely to be stayed in the hospital by 92% as compared to DKA patients precipitated by infection (aOR = 0.08, 95% CI = 0.01-0.98, p-value = 0.048) (Table 5).

Table 5: Factors that determine long hospital stay among T1DM children admitted with DKA, Bahir Dar, 2021 (n = 162). View Table 5

The purpose of this study is to determine the treatment outcome of children < 15-years-old admitted with DKA in Bahir Dar city Felege Hiwot comprehensive referral hospital.

In this study, the majority (97.5%) of admitted DKA patients were showed improvement and discharged to their homes with 8-day median length of hospital stay. This finding is much higher than the study conducted at South Asia and Jimma University Hospital in Ethiopia, where only 80.5% and 84% showed improvement and were discharged to their home respectively [13,33].

In this study, the magnitude of mortality rate is 2.5% which is higher than the previously reported mortality rate from developed nations (0.15%-0.31%) [14] and the mortality rate testified in Sudan which was 1.7% [36] the reason might be due to the high prevalence of infection(56.2%) and comorbidities (66.7%) as well as treatment complications (14,2%) in this study. However, lower than the study reported in India (8.75-12.8%) [11,27] and other developing countries like Kenya and including the Tigray region in Ethiopia (3.4-13.4%) [11,14,37].

Concerning hospital stay, although no clear cut-off point is set about when to say, there is a long hospital stay for patients admitted with DKA, most clinical experts have a common conscience for a longer hospital stay, if and only if, the patient stayed/admitted for more than seven days in the hospital with successful treatment by prompt correction of hyperglycemia, diabetic acidosis and electrolyte disturbances [34]. Therefore, the findings of this study pointed out a longer hospital stay (8 medians) days to be discharged from the hospital as compared to the study conducted in the united states (2.5) days [32], Al-Azhar University in Gaza (5.88 ± 2.55) days [35], and 3.7 to 3.4 days in another study; Even some clients can be discharged within 24 hours of hospital stay despite, the case is with sever DKA [7,38]. However,the finding was found to be equivalent to the study reported in Kenya (8 medians) days [22]. This discrepancy in treatment outcome; inpatient recovery, mortality rate, and length of hospital stay can be due to differences in treatment protocol implemented by each health care institution and population characteristics, sample size, study design, and overall healthcare system including resource allocation.

Regarding determinant factors, residence of the participants was found to be significantly associated with length of hospital stay. The study showed that, patients from the rural area had 4.31 times more likely to stay in the hospital for a longer time as compared to those patients living in an urban area (aOR = 4.31, 95% CI = 1.25-14.80). This can be due to the shortage of emergency service transportation to access immediate medical management [13,11], which again complicates the case [11]. And the finding is supported by the study conducted in Turkey [39].

Those patients having a family history of diabetes mellitus had 88% less likely to stay in the hospital for a longer time as compared to patients with no family history of diabetes mellitus (aOR = 0.12,95% CI = 0.02-0.64). And the reason behind this is not inclusive yet.

The amount of serum glucose at admission was also significantly associated with longer hospital stays. Length of hospital stay increases by one day, as the serum glucose value increases by one unit (aOR = 1.01, 95% CI = 1.00-1.02). This could be due to severe hyperglycemia leading to severe acidosis/dehydration, electrolyte disturbances, and later altered sensorium at presentation [11,38,39]. Which again over burdened the situation by increasing the number of patients to undergo further complications as was supported by the findings in this study.

In this study, precipitating factors of DKA by insulin skipping/omission were less likely associated with longer hospital stay by 92% as compared with that patient’s DKA precipitated by infection (AOR = 0.08, 95% CI = 0.01-0.98).

This is because, having concurrent infection influences T1DM disease progression with hurt of normal glucose metabolism which can lead worsening of optimal glycemic control. Infection can also reinforce hormones in triggering blood glucose level to be rised and can complicate the management process [29]. The finding is in line with the study conducted in Addis Abeba, Jimma, and Keneya [11,13,22].

A patient with abdominal pain at the time of client presentation is 4.28 times more likely to be stayed in the health institution than patients with no abdominal pain (aOR = 4.28, 95% CI = 1.11-15.52). The finding is similar with study reported in Kenya [22] and Turkey [39].

Similarly, the time in which the patient free from/got out of DKA was associated with longer a hospital stay in this study. Those patients who get out of DKA in greater than 72 hours were 6.39 times more likely to stay in hospital compared to those patients who get out of DKA for less than 24 hours (aOR = 6.39, 95% CI = 1.09-37.50). This might be due to differences in hyperglycemia state, clinical presentation, and delay in management [37,40].

In general, this study can bring out positive implications for clinical care, health service management, and research in the area of diabetic specialization. Clinically, the health care worker can identify predictors associated with longer hospital stay among type one diabetic children admitted with DKA at clinical setup. Health care managers can access current evidence about overall treatment outcomes of DKA among T1DM children and take remedial action to strengthen service delivery by clinicians. Researchers can also be motivated to conduct further research in this area by taking this study as preliminary findings.

Management protocol was generally administered according to Ethiopian standard treatment guideline; However, poor practice of serum potassium assessment as well as potassium supplementation was noted. In this study, the majority (97.5%) of admitted DKA patients were showed improvement and discharged to their homes within 8-day median length of hospital stay and with very low mortality rate and high management complications (14.2%). The study also suggests that, the times in which the majority of patients get out of DKA were between 24 and 48 hours.

Residence, family history of T1DM, glycemia at admission, DKA precipitating factors, and DKA presentation specifically, abdominal pain, and time in which the patients got out of DKA were significantly associated with a long hospital staying the multivariable logistic regression model of less than 5% level of significance.

Thus, to achieve the intended treatment outcome early in time, clinicians and other stakeholders should focus on diabetic ketoacidosis presentation and precipitating factors with possible multicenter studies in this regard.

Since the data were collected from medical records, the detailed treatment protocol and some of the important laboratory results were not addressed. Another limitation is that this study was conducted in one hospital only, which may be difficult to generalize the findings to another hospital in the region.

In order to conduct this research, we tried to consider the declaration of Helsinki’s ethical principles for medical research. Ethical clearance and approval wereobtained with ethical review board number (CMHS/IRB number01-008) decided on the date of February 26, 2021. Written supportive letters, as well as permission and/or informed consent, have been taken from the pediatrics department of the hospital and from the dataset owner to use the information in databases/repositories for this research on behalf of the patients. As this was a retrospective study, informed consent from individual patient was not requested because the authors and data collectors had no physical contact with them and the data were collected from their medical records after their discharge from the hospital. Informed consent from each study participant, for ethics approval, had been waived by the institutional Review Board of ethics committee. Information in the data extraction was anonymous. This study had no danger or negative consequences for the study participants. Medical record numbers were used for the data collections and personal identifiers of the patients were not used in this research report. Access to collected information was limited to the principal investigator and confidentiality had preserved throughout the time.

Not applicable.

Data will be available upon request from the corresponding author.

The authors report no competing interest in this research work.