Trench Fever is caused by Bartonella quintana, a small fastidious gram-negative rod organism carried by the body louse. We report a case of a 62-year-old woman who was admitted to a hospital in central Texas for a two-week history of fever and malaise. She was initially treated for Q fever which is usually caused by inhaling dust particles contaminated by infected animals, given that she was regularly around farm animals, but when her extensive infectious disease panel came back negative, the search was expanded and she was found to have positive B. quintana serology titers. She recovered on Doxycycline therapy for 14 days and discharged to continue it for 4 more weeks as outpatient and to follow up in the clinic.

Bartonella quintana, Body louse, Q fever, Quintan fever, Trench fever

Trench fever, caused by Bartonella quintana or B. quintana, first plagued soldiers in the trenches in World War I [1]. The human body louse acted as the vector [2]. The disease is contracted through the feces of the infected louse into broken skin surfaces [3]. Recent B. quintana outbreaks have been found amongst chronic alcoholics as well as indigent and homeless populations [4]. Trench Fever can present with mild influenza-like symptoms to a debilitating disease process: Bacteremia; endocarditis; or bacillary angiomatosis [1]. Definitive diagnosis is by isolating the organism in blood or tissue culture.

A 62-year-old woman with prior hypertension, hyperlipidemia, arthralgias, cervicalgia, chronic back pain, chronic kidney disease stage 3, and gastroesophageal reflux disease presented to the emergency department with complaints of ongoing fever and malaise for the previous two weeks. She tried taking Tylenol at home with minimal relief. She also complained of lethargy, body aches, chills, and a mild intermittent cough during this time. She denied vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, dysuria, sore throat, neck pain, confusion, or increased urinary frequency.

She had seen her primary care provider in the clinic on day 1 of her illness and was diagnosed with a possible upper respiratory infection vs. sinus infection vs. the flu. She was instructed to take Cefuroxime and if she did not improve to stop treatment in 2-3 days. On day 7 with this antibiotic treatment, she developed a pruritic skin rash all over her body. She endorsed having contact with sick grandchildren who had similar symptoms that lasted for 2 weeks as well. She lives at home with her husband, along with their goats and cats. She endorsed some mosquito bites lately but no other insect or tick bites. She reported no recent travel. She is generally very active and healthy.

At the emergency department, vital signs were remarkable for blood pressure of 99/65, heart rate of 133, respiratory rate of 26, and maximum body temperature recorded in a 24-hour period of 102.5. Labs were practically normal. EKG showed sinus tachycardia with a heart rate of 120 and chest X-ray showed no acute process. She was given Tylenol 1 g, 2500 cc normal saline, and started on Levaquin and intravenous Zosyn empirically for sepsis of unknown source. On physical exam, she was alert and oriented as well as appeared listless and plethoric in the face. Concentration and short-term memory decreased from baseline on exam according to husband. Pupils were equal and reactive to light, extra-ocular muscles were intact, no sinus tenderness was present, and both tympanic membranes were intact and unremarkable. Her oropharynx did not show any erythema or exudates. There was no cervical lymphadenopathy. She was negative for neck stiffness, Kernig's, and Brudzinski's. She had tachycardia on exam, with no murmur, rub or gallop. Her lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally with no wheezes, rales, or rhonchi. Her abdominal exam was unremarkable for any organomegaly or masses palpated. Her skin exam was normal with no apparent rash, lower extremity edema, or skin changes. Cranial nerves II-XII were grossly intact.

She was admitted to the Family Medicine Hospital service for fever of unknown origin with thrombocytopenia and elevated liver function tests. Given her exposure to animals (on account of living on a farm with goats and cats and working at a veterinary clinic), the potential exposure to a wide variety of zoonotic illnesses vs. mosquito-borne illness vs. viral syndrome was considered. She was initially treated with broad spectrum antibiotics (Vancomycin/Zosyn). Her fevers persisted and infectious disease was consulted. Initially, Q fever was entertained as the highest suspicion. A multitude of tests were subsequently obtained with negative results for toxoplasma, Ehrlichia, Histoplasmosis, brucella, coccioides, Q-Fever, arbovirus, malaria smear, typhus, cat scratch, bartonella, dengue, chikungunya, zika, west nile, hepatitis panel, influenza pcr, stool pathogen panel, and HIV.

Hematology-oncology was consulted as there was concern that her persistent fever might be due to an occult cancer. Peripheral blood smear was obtained that showed elevated absolute lymphocytes, thrombocytopenia, and red blood cells with Rouleaux formation that was thought to be possibly due to chronic lymphocytic leukemia but ultimately felt to be due to reactive leukocytosis. Gastrointestinal consult was also obtained due to her elevated liver function tests and thrombocytopenia. Liver biopsy was obtained that showed acute hepatitis suggestive of an infectious process. Serology came up positive for IgG/IgM Rocky Mountain spotted fever. She was started on intravenous Doxycycline and subsequently switched to oral Doxycycline which she tolerated well for 24 hours without fever. She was discharged to continue a further 3 days of oral Doxycycline to complete a total of 14 days therapy.

Four days after discharge and after completing her antibiotic course, she was readmitted due to complaint of fever. While in the emergency department, computerized tomography of her abdomen/pelvis obtained showed evidence of recent liver biopsy but no evidence of inflammation to suggest infection and no intra-abdominal abscess. She was admitted with Vancomycin/Zosyn. Review of infectious studies prior to recent discharge showed positive B. quintana as well as positive CMV. Her antibiotic regimen was changed to Doxycycline and Gentamicin due to the concern for Trench fever. She continued to lose intravenous access and her Gentamicin was discontinued in favor of Doxycycline as monotherapy. Infectious disease was consulted again regarding the positive serologies for B. quintana and CMV. They felt that her continued fevers were possibly confounded by drug reaction to Cefuroxime that she had been given prior to her last admission. They recommended 4 weeks of continued Doxycycline as outpatient and to follow up in the clinic.

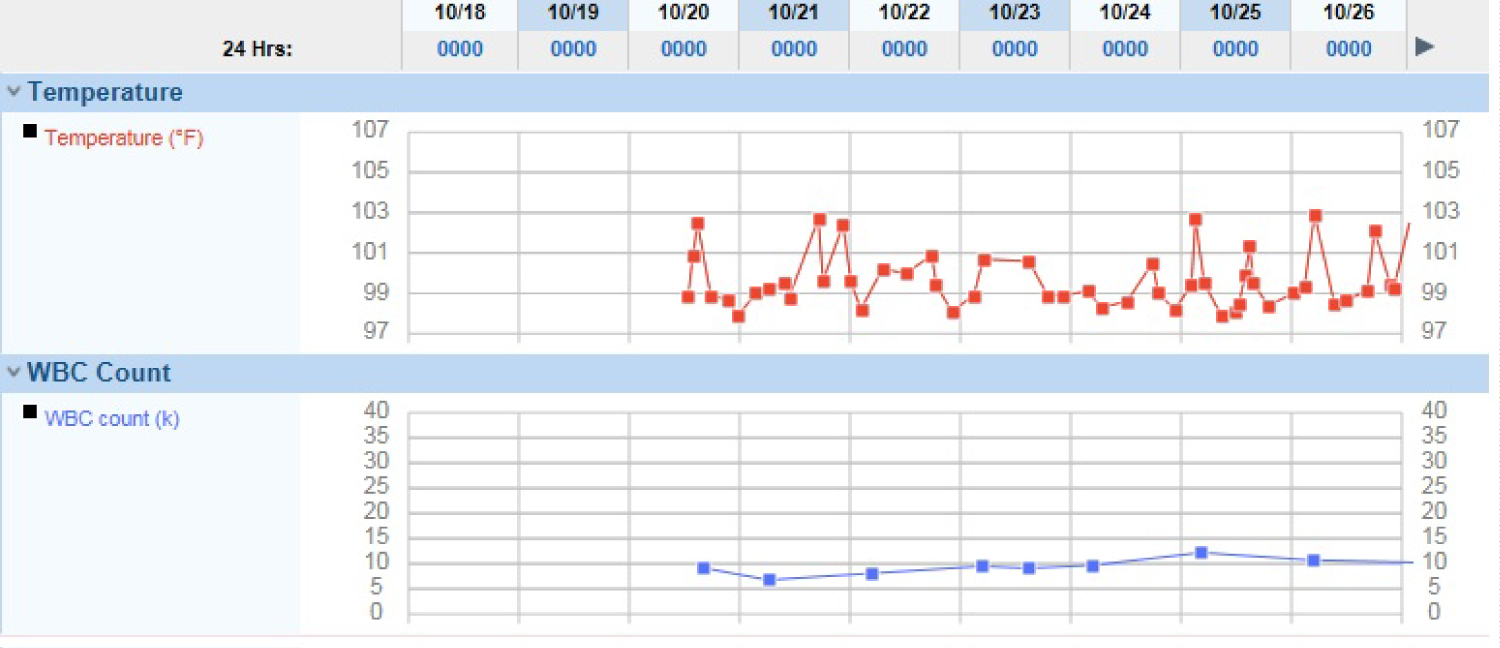

It has been reported that B. quintana should be considered a zoonotic infection [5]. In a study of 89 veterinary personnel in Spain, two asymptomatic veterinary personnel were serologically positive to B. quintana polymerase chain reaction without any history of lice, considered the primary human vector [6]. The positive cut-off was 1:64 [6], the same cut-off we used as a positive serology marker in our patient. Classic trench fever include quintan fever of 5-day intervals with asymptomatic periods, debilitating typhoidal illness, maculopapular rash, conjunctivitis, severe headache, myalgias, and splenomegaly [6]. This patient had waxing and waning temperatures while hospitalized (Figure 1), myalgias, a subtle rash, but no splenomegaly. Usually, the incubation period for Trench fever after the primary infection is 15-25 days and the first fever episode can last 2-4 days with a relapse every 4-5 days [5]. Our patient had a more frequent relapse of her fever.

Figure 1: Temperature and white blood cell count during admission.

View Figure 1

Figure 1: Temperature and white blood cell count during admission.

View Figure 1

The severity of B. quintana infections depends on the immune status of the patient. Without treatment, B. quintana can cause high mortality, with associated bacteremia or endocarditis most effectively treated with Gentamycin and Doxycycline for 4-6 months [7]. In our patient, there was no evidence of endocarditis, but other isolated infections from B. quintana infection have been described such as in another immunocompetent man who had a parotid gland infection [8]. Overall, it is difficult to ascertain the incidence of B. quintana in the US as "only a small portion of the infected population will develop overt clinical disease [9]". From our research and to the best of our knowledge, Trench fever and infection with B. quintana has not been described in Central Texas.

None.

All authors contributed equally to the conception, drafting, and final approval of the manuscript.