Eosinophilic lung diseases are a group of heterogeneous disorders characterized by blood eosinophilia and pulmonary infiltrates. These conditions are very rare in Pediatric sunset.

A 12-year-old nonsmoking asthmatic girl was admitted for general malaise and dry fatiguing cough. Diagnostic course reveled marked hypereosinophilia and chest radiography indicated multifocal and circumscribed bilateral pulmonary areas of consolidation. Bronchoscopy excluded the presence of neoplastic cells but marked hypereosinophilia was found in bronchoalveolar lavage. The increased number of eosinophils in blood and in bronchoalveolar lavage, the radiological findings were suggestive of Chronic idiopathic eosinophilic pneumonia.

Chronic idiopathic eosinophilic pneumonia is a rare disease, especially in Pediatrics. Often misdiagnosed, the treatment is based on corticosteroid administration, but there is no consensus on the right management of the disease.

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, Carrington disease, Children

ELD: Eosinophilic Lung Diseases; ICEP: Chronic Idiopathic Eosinophilic Pneumonia; AEP: Acute Eosinophilic Pneumonia; CT: Chest Computed Tomography; BAL: Bronchoalveolar Lavage

Eosinophilic lung diseases (ELD), also known as Eosinophilic pneumonia, are a group of heterogeneous disorders with alveolar and/or blood eosinophilia and pulmonary infiltrates on chest imaging. These conditions are divided into two groups: Secondary forms (such as allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosi, bronchocentric granulomatosis, parasitic infection, drug reaction, eosinophilic vasculitis) and idiopathic forms (simple pulmonary eosinophilia, acute eosinophilic pneumonia [AEP], chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome) (Table 1).

Table 1: Classification of the eosinophilic lung diseases. View Table 1

Chronic idiopathic eosinophilic pneumonia (ICEP), or Carrington disease, is particularly rare in pediatric population, characterized by pulmonary opacities associated with tissue or peripheral eosinophilia and respiratory symptoms lasting more than two weeks [1].

Here we report an unusual pneumonia presentation, antibiotic - resistant, in an Albanian teenager.

A 12-year-old nonsmoking asthmatic girl was admitted to Hospital in other country, with a history of ten days of cough, difficult breathing and asthenia. At admission, she had severe respiratory distress with chest wall retractions and 90% O2-saturation in room air, needing oxygen supplementation. She also received inhaled corticosteroid and β2 agonist without any improvement.

Chest x-ray showed bilateral multiple thickening areas with mediastinal pleural involvement confirmed by CT scan. Pleural and bone marrow biopsy were performed in suspicion of malignancy, with negative response. No clinical and radiological improvement were obtained during antibiotics and steroid treatment, for these reasons the patient was transferred to our Hospital.

At the admission in our Paediatric Division, she complained general malaise and dry fatiguing cough but her vital signs were normal (temperature 36.7 ℃, blood pressure 110/60 mmHg, pulse rate 87 bpm). Oxygen-saturation in room air was 96% with respiratory rate 20 per minute.

Clinical evaluation revealed that her breathing sounds were slightly decreased without crackles or wheezing.

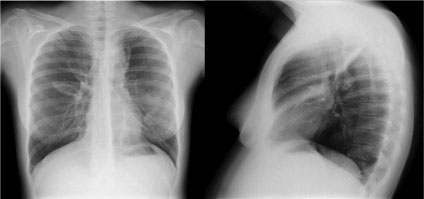

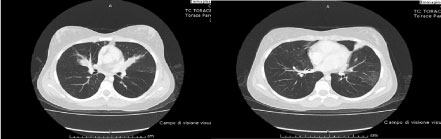

Chest radiography indicated multifocal and circumscribed bilateral pulmonary areas of consolidation with lamellar aspect and minimum thickening of pleural fissure, confirmed by Lung ultrasound (Figure 1). Chest Computed Tomography (CT) scan was performed, showing multiple areas of parenchymal consolidation with many bronchiectasis stuffed of hypodense material and circumscribed ground glass opacity in the lower lungs (Figure 2). Complete Blood Count revealed marked hypereosinophilia, confirmed by microscopic peripheral blood examination (Eosinophil 37%, 3330/uL). Tuberculin skin test, Quantiferon-Gold-in-Tube and microbiological tests were all negative. Sweat test showed normal values of chloride. Thus, we extended the investigation panel with tumour markers, levels of angiotensin converting enzyme and alpha-1antitrypsin and immunological assays (Antinuclear antibody, Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, rheumatoid factor, C3, C4), all in normal laboratory range. IgE levels were high (459 Ku /l, normal value < 100) and skin prick tests were positive for inhalant allergens (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and farinae, Graminaceae). The lymphocyte subsets instead showed a slight decrease of the normal CD4/CD8 T cells ratio (ratio 0.6). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was also elevated. No signs of cardiac dysfunction were found at Electrocardiogram and Doppler echocardiography [2].

Figure 1: Chest X-ray of the patient.

View Figure 1

Figure 1: Chest X-ray of the patient.

View Figure 1

Figure 2: CT scan of the chest in our patient.

View Figure 2

Figure 2: CT scan of the chest in our patient.

View Figure 2

Bronchoscopy excluded the presence of neoplastic cells but marked hypereosinophilia (38%) was found in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). There was no evidence of bacterial, fungal or mycobacterial infection in culture of BAL. The increased number of eosinophils in blood and in BAL, the radiological findings with the characteristic ground glass pattern and the persistence of symptoms for about 4 weeks were suggestive of ICEP. Oral steroid therapy was started (prednisone, 2 mg/kg/die for the first 30 days), slowly tapered in 6 months, with gradual and progressive radiological and clinical normalization.

Chronic idiopathic eosinophilic pneumonia, first described by Carrington, et al. in 1969, is a rare disease especially in pediatric population [3]. The estimated prevalence is 1:100.000, women are more frequently affected than men [3]. More than 50% of cases have a history of atopy and asthma [4]. The clinical manifestation is usually insidious at the onset, characterized by non specific symptoms and signs such as fever, cough, dyspnea, wheezing, sputum production, night sweat and weight loss [5]. Diagnosis is not easy, frequently delaying the treatment. Clinical presentation is progressive and often insidious [3,5].

Blood eosinophilia, mild or moderate but occasionally severe and increased serum IgE levels are features of this condition, interesting two-thirds of affected patients [4]. Eosinophilic leukocyte were discovered by Ehrlich at the end of the 1800s, but only in the last years findings revealed the role of these cells and their granules in the pathogenesis of diseases. Actually, the mechanisms of eosinophilic pathways is not completely known, but several interactions involving a complex network of cells, tissues, cytokines and chemokines could explain systemic manifestations of eosinophilic inflammation. Therefore, it is important to see at eosinophilic syndromes as systemic disorders [6,7].

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate in ICEP is usually elevated, and it is also described thrombocytosis [4,8]. The eosinophils in the BAL fluid are very high [9]. Histologic examination of affected lung typically shows marked infiltration of eosinophils and lymphocytes in the alveoli, peribronchiolar-perivascular tissues and in the interstitium [10,11]. The essential histologic differences between AEP and ICEP are related to the severity of basal lamina damage and the amount of intraluminal fibrosis [12].

Chest radiological findings in ICEP are: non-segmental peripheral airspace consolidation ("photographic negative shadow of pulmonary edema", in less than 50% of cases) especially in the upper lobes, ground-glass opacities, nodules and reticulation (especially in the later stages of ICEP). Pleural effusion is observed in less than 10% of cases. Computed Tomography shows typical non-segmental areas of consolidation and linear bandlike opacities, when performed more than 2 months after the onset of symptoms, [1]. Actually, diagnostic criteria described by Marchand, et al. are validated only for adult population [13].

Giovannini-Chami, et al. proposed modified diagnostic criteria for children [14] (Table 2):

Table 2: Diagnostic Criteria for ICEP e IAEP. View Table 2

• Diffuse pulmonary alveolar consolidation with air bronchogram and/or ground-glass opacities, especially with peripheral predominance;

• BALF eosinophilia > 20% and/or peripheral blood eosinophilia > 1 × 109 cells/L;

• Respiratory symptoms present for more than 4 weeks;

• Absence of other known causes of eosinophilic lung disease;

• Consistent open lung biopsy for cases without initial dramatic clinical and radiological improvement on first- line treatment.

Therapeutic approach in terms is not standardized [8]. The natural course of the disease, when not treated, is not well known even if some cases of spontaneous resolution have been reported, but there is general agreement that treatment of ICEP is based on oral corticosteroids. Unfortunately high rates of relapse (> 50%) are described during decalage or after stopping corticosteroid treatment. It has been suggested that relapses of ICEP may be less frequent in patients under inhaled corticosteroid treatment after stopping oral corticosteroids, but this is controversial [13].

Our patient showed a good response to this approach: Clinical conditions and findings improved quickly and disappeared in few months of treatment with no relapse recorded during two years of follow up.

No external funding for this manuscript.

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.