Autoimmune Hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic necroinflammatory liver disease of unknown etiology associated with circulating autoantibodies and high serum globulin level. Systemic lupus erythematous (SLE) is a disease of unknown etiology in which tissues and cells are damaged by pathogenic autoantibodies and immune complex, affecting multiple organs including the liver, kidney, and CNS. AIH has been considered to occur infrequently in SLE. We report a 42-year-old female patient with an overlap syndrome involving autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) and systemic lupus erythematous (SLE). The patient presented with jaundice, arthralgias, fatigue, jaundice, mild fever, and abdominal discomfort. Laboratory tests revealed severe liver dysfunction, a positive ANA/anti-dsDNA test. A liver biopsy showed acute hepatitis with severe inflammatory activity that goes with autoimmune hepatitis. The patient satisfied the international criteria for both SLE and AIH. Clinical symptoms and laboratory findings of SLE improved with appropriate treatment by corticosteroids and azathioprine, and remission of the liver disease was achieved as well.

Systemic lupus erythematous, Elevated liver enzymes, Autoimmune hepatitis, Liver histology, Lupus hepatitis, International AIH score

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystem autoimmune disorder involving various organs such as kidneys, skin and the central nervous system. Liver involvement is normally not part of the spectrum of SLE but is seen in up to 60% of SLE patients [1]. Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is also an autoimmune disease-causing inflammation of the liver. AIH is characterized by histological changes of interface hepatitis and plasma cell infiltration of the portal tracts, hypergammaglobulinemia, and autoantibodies [2,3].

The clinical presentation of AIH ranges from asymptomatic disease recognized only by incidentally ascertained biochemical abnormalities to an acute or even fulminant hepatitis. Female predominance and occurrence peaks in early adult life and in the 4th decade of life are characteristic [4].

Although the liver is not a major target for damage in SLE, clinical and biochemical evidence of liver abnormalities are common. The co-occurrence of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) and SLE is considered to be rare and only few case reports have been published so far.

Whether AIH and SLE-associated hepatitis are two distinct entities remains unclear. Several clinical and histological features have been used to discriminate AIH from SLE, since complications and therapy are very different in the two conditions [5]. In this report, we present a patient with an overlap syndrome involving autoimmune hepatitis and SLE.

A 42-year-old female patient was admitted in March 2017 with complaints of malaise, jaundice, polyarthralgia, abdominal distention and discomfort, and low-grade fever, evolving since 3 weeks. She has been treated by an orthopedic surgeon for arthralgias by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory and myorelaxant drugs without improvement. The patient is known to have hypothyroidism treated by Eltroxine 200 microgs/d since 5 years. She was married at 18-years-old and have three kids. Family history was negative for rheumatic or inherited liver disease, including SLE and AIH. She had no risk factor for blood transmitted disease.

On physical examination, the patient had hepatomegaly and splenomegaly and she had a history of photosensitivity.

Complete blood count revealed hemoglobin of 96 g/L, white blood cell count 9800/mm3 and platelet count 208.000/mm3, a peripheral blood smear showed no specific features. Microscopic examination of the urine was normal. Biochemical tests showed evidence of liver dysfunction. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was 572 IU/L (N: 5-40 IU/L), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 650 IU/L (N: 8-33 IU/L), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase 320 IU/L (N: 5-40 IU/L), alkaline phosphatase 215 IU/L (N: 35-129 IU/L), total bilirubin 61 mg/L (N: 1-12 mg/L), conjugated bilirubin 52 mg/L (N: 0-3 mg/L), and prothrombin activity 89% with International normalized ratio 1.32 (N: 0-1).Serum creatinine, BUN and fibrinogen were normal. Here lab tests three months prior to presentation were normal.

Wilson's disease was ruled out because of normal serum ceruloplasmin. C-reactive protein level were elevated (130 mg/L respectively). Coombs-positive hemolytic anemia was detected. Serum immunoglobulin G and M levels were increased, serum plasma electrophoresis showed hypoalbuminemia with a polyclonal increase in total gamma globulins. Serological tests showed positive results for serum antibodies against nuclear antigen (ANA) 1/6400 IU/L and double-stranded DNA, and the serum levels of C3 and C4 were normal. Tests for antiphospholipid antibody and anticardiolipin antibody were positive. Antibodies against smooth muscle (SMA), liver/kidney microsomes (LKM), anti-mitochondrial M2 antibody (M2-AMA), anti-soluble liver antigen/liver-pancreas (SLA/LP), anti-M2-E3, antibody to liver cytosol (LC-1) and extractable nuclear antigen (ENA) were negative.

Viral serological tests including antibodies against hepatitis viruses A, B and C, Epstein Barr, Cytomegalovirus (CMV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were negative.

Abdominal ultrasonography and color doppler ultrasonography revealed hepatosplenomegaly with mild perihepatic liquid indicating hepatitis.

Three days after symptomatic treatment, the patient's laboratory tests and clinical symptoms were worsening: serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was 1105 IU/L (N: 5-40 IU/L), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 910 IU/L (N: 8-33 IU/L), total bilirubin 110 mg/L (N: 1-12 mg/L), Prothrombin activity 63% and international ratio 2.1, microalbumin ratio 80 mcg/mg.

The patient showed 6 of 11 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for SLE which classified her as definite SLE [6]. Abdomino-pelvic CT scan showed no significant abnormalities.

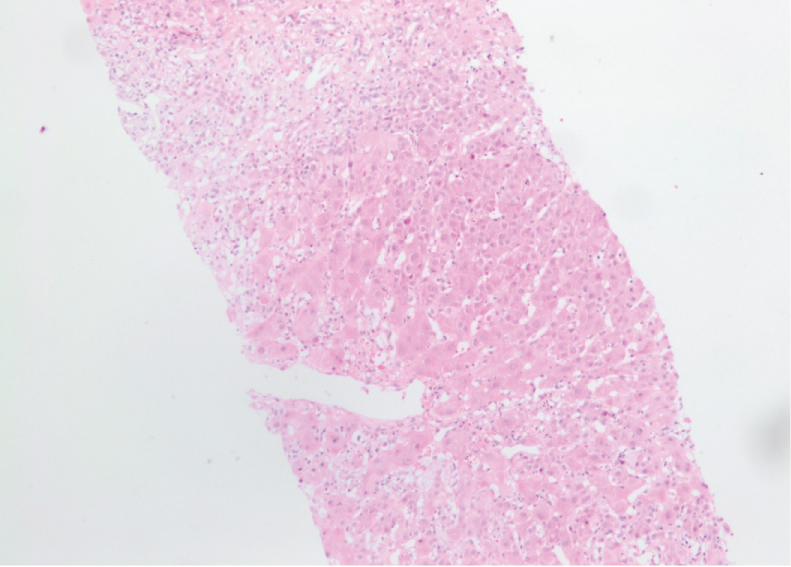

Liver biopsy showed acute hepatitis with severe inflammatory activity. The hepatic architecture is very reworked with 12 enlarged fibroadenomatous portal spaces, seat of fibrosis more or less important with a tendency to confluence (bridging) inter-portal. The lobules are dissociated by a polymorphic inflammatory infiltrate with extensive hepatocyte necrosis (< 50% of the portal circumference) and Councilman body formation. The remaining hepatocytes are surrounded by edematous fibrosis (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Beginning of cirrhotic lobulations related to a very active hepatitis, compatible with an autoimmune origin. Salem Ch, Makhoul E, Murr T, et al. View Figure 1

Figure 1: Beginning of cirrhotic lobulations related to a very active hepatitis, compatible with an autoimmune origin. Salem Ch, Makhoul E, Murr T, et al. View Figure 1

These findings suggested an overlap syndrome involving SLE and autoimmune hepatitis. The patient was started on treatment with oral prednisolone 1 mg/kg per day (60 mg/d). Because of the ongoing high transaminase levels, azathioprine (AZA) was added (50 mg/kg per day for the first week and than 100 mg/day for 6 months), prednisolone was gradually tapered (by 10 mg/week till 30 mg daily, than tapered by 5 mg/week till 20 mg daily, than tapered by 2.5 mg/week till 5 mg daily for 6 months).

Clinical symptoms and laboratory findings of SLE improved, and a remission of acute hepatitis was achieved in the case. Complete biochemical remission including normalization of transaminases as well as IgG levels was achieved after four months of treatment.

The patient was regularly seen at the outpatient clinic for follow-up visits.

Systemic lupus erythematous (SLE) is a multisystem autoimmune disorder involving various organs such as kidneys, skin and the central nervous system. Liver involvement is normally not part of the spectrum of SLE, but is seen in up to 60% of SLE patients [1]. The criteria for the diagnosis of SLE have been proposed by the American College of Rheumatology [6].

The difference between the hepatic involvement in SLE and AIH has not been clearly defined due to similarities in the clinical and biochemical features. Liver involvement in patients with SLE is well documented but is considered rare [5].

It has been suggested that patients with AIH may be at an increased risk of developing systemic connective tissue diseases. Conversely, patients with systemic connective tissue diseases may be at an increased risk of AIH [7].

The criteria for the diagnosis of AIH in adult patients have been established by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) [8]. Diagnostic criteria in accordance with the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group and the "simplified criteria" are based on elevation of Immunglobulin G (IgG), demonstration of characteristic autoantibodies, histological features of hepatitis and the absence of viral disease [8,9].

The clinical presentation of AIH ranges from asymptomatic disease recognized only by incidentally ascertained biochemical abnormalities to an acute or even fulminant hepatitis. Female predominance and occurrence peaks in early adult life and in the 4th decade of life are characteristic [4].

Although AIH and SLE-associated hepatitis are considered as two different entities [10], both have features of an autoimmune disorder, such as the presence of polyarthralgia, hypergammaglobulinemia and positive tests for ANA, SMA, anti-ribonucleoprotein antibody, and anticardiolipin antibodies [11].

Fortunately, several histological and clinical features can differentiate AIH from SLE. The presence of cirrhosis or periportal (interface) hepatitis, periportal piecemeal necrosis associated variably with lobular activity, and rosette formation of liver cells support the diagnosis of AIH, but do not exclude SLE. The presence of only lobular hepatitis is more compatible with SLE. In both "lupus hepatitis" (or "SLE hepatitis") and treated AIH, the inflammatory infiltrate consists mainly of lymphocytes, whereas in untreated AIH, these cells are mixed with plasma cells [5]. Our patient had acute hepatitis with severe inflammatory activity characterized a hepatic architecture with 12 enlarged fibroadenomatous portal spaces, seat of fibrosis more or less important with a tendency to confluence (bridging) inter-portal. The lobules are dissociated by a polymorphic inflammatory infiltrate with extensive hepatocyte necrosis (< 50% of the portal circumference) and Councilman body formation.

ANA and Anti-DsDNA were the only positive serological markers; its positivity is sufficient to diagnose AIH. Consequently, these findings strongly support the diagnosis of AIH [12].

The patient was evaluated for hereditary (Wilson's disease), infectious (hepatitis A, B, C and CMV, EBV), and drug-induced liver injury, some of which may have autoimmune features [13]. When the simplified scoring system for AIH was applied, patient had a score of 8, which is sufficient for a definite diagnosis of AIH [6] (Table 1).

Table 1: Simplified criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis [9]. View Table 1

Specific markers for AIH, which usually do not occur in SLE, are soluble liver antigen (SLA), Liver-pancreas, smooth-muscle antibody (SMA) with specificity for F-actin and microsomal autoantigens, such as anti-liver kidney antibodies (anti-LKM antibody) [4].

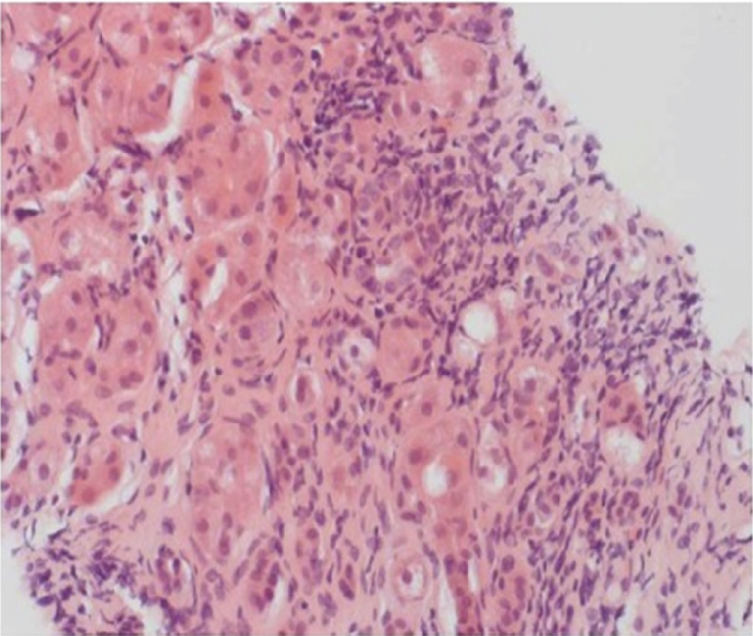

While these markers may help to segregate AIH coincident with SLE serologically, liver histopathology represents the key feature that distinguishes AIH in SLE from nonspecific hepatic involvement in SLE. In patients with AIH liver histopathology shows characteristic lesions, such as interface hepatitis, rosetting of hepatocytes, emperipolesis and -consecutive to inflammation-fibrosis (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Typical histopathology of a patient with autoimmune hepatitis. Cirrhotic changes of the liver parenchyma with interface hepatitis. The portal and periportal inflammatory infiltrate are composed of lymphocytes, monocytes/macrophages and plasma cells (haematoxylin and eosin staining × 200) [4]. View Figure 2

Figure 2: Typical histopathology of a patient with autoimmune hepatitis. Cirrhotic changes of the liver parenchyma with interface hepatitis. The portal and periportal inflammatory infiltrate are composed of lymphocytes, monocytes/macrophages and plasma cells (haematoxylin and eosin staining × 200) [4]. View Figure 2

Hepatic involvement in patients with SLE is well documented but considered to be rare [14].

Our patient met the American College of Rheumatology criteria for SLE as well as the criteria for AIH [10]. She had the characteristic photosensitivity, polyarthralgia, arthritis, renal disorder, hematologic disorder, and was positive for antibodies against native DNA and nuclear antigen. She was started on prednisolone and azathioprine and achieved complete remission for her SLE and her liver disease.

We believe that our patient has the AIH-SLE overlap syndrome. The AIH-SLE overlap syndrome has been reported to respond rapidly to steroid therapy and the prognosis is generally good [15].

Corticosteroid therapy is effective in all forms of AIH and the combination of prednisone and AZA is preferred for purpose of steroid sparing. Relapse is common, and long-term low-dose prednisone or AZA therapy is the treatment of choice after a patient has had multiple relapses. Sustained remission is achievable, even after relapse and maintenance regimens need not be indefinite [16].

In conclusion, AIH and SLE are distinct diseases, whose combination of clinical symptoms and diagnostic markers overlap. While SLE and AIH are rarely diagnosed as concomitant diseases in one patient, hepatic involvement in patients with SLE is sometimes observed during the course of disease. We suggest that AIH needs to be considered in the differential diagnosis of any SLE patient with elevated liver enzymes. Liver biopsy is therefore crucial in these patients.

The authors declared no conflict of interest.