Clinical diagnosis is one of the most demanding tasks, even for experienced physicians. In daily clinical practice, common diseases may require, developed skills [1]. Not only by the intrinsic difficulties of the disease itself, but also because some of them may threaten patients' life and demands a prompt and safe attention. As examples of that are sudden dyspnoea, chest pain or syncope.

When loss of consciousness happens, differential diagnosis includes syncope, epilepsy and cardiac arrest [2]. Accordingly, distinction between cardiogenic from non-cardiogenic type is the crucial step in the management of such patients. The sharp difference in prognosis between these aetiologies, often leads to an excess of needless tests [3]. The most important tool for diagnosis of syncope remains a good clinical history-taking and EKG.

In cases of syncope in patients with cardiovascular risk factors, differential diagnosis may be specially challenging.

We present the case of a patient with sequelae from a prior stroke who presented in Emergency Ward with a sudden loss consciousness.

A 57-years-old white man with antecedents of ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation and right hemiparesis due to embolic stroke six years earlier, was admitted by loss of consciousness. He had suddenly fallen to ground and started with tonic-clonic seizures that lasted a few minutes, followed by a slow recovery of consciousness with no additional neurological deficit.

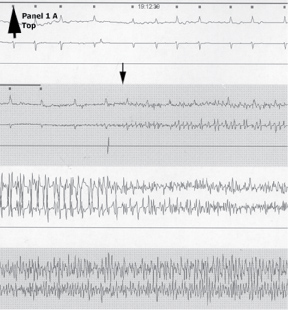

A 24-hour-EKG record -to rule out malignant ventricular arrhythmias- registered heart rhythm during a new seizure.

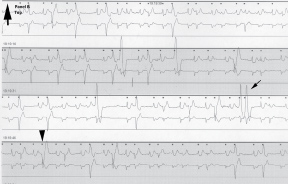

Seizure lasted one minute (Figure 1A and Figure 1B). For the following six minutes ventricular extrasistolia and ST depression (-4 mm) appeared (Figure 2). Ventricular extrasistolia was frequent and complex, with polytopia, precocity and duplets.

Figure 1A: Starting of seizure (arrow). View Figure 1A

Figure 1A: Starting of seizure (arrow). View Figure 1A

Figure 1B: Ending of seizure (arrow). View Figure 1B

Figure 1B: Ending of seizure (arrow). View Figure 1B

Figure 2: Complex ventricular extrasitolia (arrowhead) and duplets (arrow). View Figure 2

Figure 2: Complex ventricular extrasitolia (arrowhead) and duplets (arrow). View Figure 2

Given ST segment depression a coronariography was performed. Angiography showed apical acinesis, anterolateral discinesis and distal occlusion of anterior descendent and circumflex arteries. One stent was implanted in each stenosis with no complications. The patient recovered uneventfully.

In many cases of syncope, a thorough complementary study is often needless. However, in patients with cardiovascular diseases or at risk of cardiogenic syncope, as is the present case, it is necessary to rule-out cardiac structural abnormalities and malignant arrhythmia to formulate a conclusive diagnosis.

Our patient suffered a seizure while carrying an external EKG-Holter device that recorded the ST-segment depression suggestive of myocardial ischaemia. The increase in oxygen consumption triggered by muscular exercise secondary to tonic-clonic muscular activity served as a heart stress test leading to diagnosis and treatment of a silent coronary artery disease.

In patients with loss of consciousness and concomitant cardiovascular risk factors or sequelae from prior events, a proper study to refine aetiology may be required.