To identify the prevalence of Barrett's esophagus (BE) in patients with nasopharyngeal reflux (NPR) presenting to a tertiary rhinology practice in 2017, and to assess for any correlation with the presence of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Demographic data, self-reported symptoms and relevant past medical history were compiled from a standardized intake questionnaire. Symptoms were grouped into 3 categories: NPR, laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) and GERD. Descriptive and nonparametric statistical analyses were performed.

Out of 807 new patients seen in 2017, 86 (10.7%) were referred to gastroenterology (GI) with NPR-associated symptoms, based on pre-existing referral indications. Forty-three patients were evaluated by a gastroenterologist, and 25 underwent EGD with pathology report available for review. BE was identified in 6/25 (24%) patients. Five of these six patients (83.3%) reported either mild or no GERD symptoms. No patient factors or presenting symptoms were significantly associated with the diagnosis of BE.

This data in consecutive new patients suggests that compliance with referral recommendations is poor among NPR patients and that the incidence of BE in this population may be higher than that generally reported among GERD patients. This experience strengthens indications for referral for EGD to rule out BE, and it highlights the importance of patient education to improve compliance.

Esophageal cancer, Gastroesophageal reflux, Screening, Reflux esophagitis, Laryngopharyngeal reflux, GERD

Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is known to increase patients' risk of developing Barrett's esophagus (BE). BE is widely recognized as a precancerous condition whereby the protective squamous epithelium of the distal esophageal mucosa is replaced by columnar intestinal epithelium. Individuals with BE are at much higher risk (estimated between 30-120 X>) of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) than the general population [1]. While development of BE has been previously emphasized as a concern for those with long-standing laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) [2,3], it is not described as a specific concern for those who have predominantly nasopharyngeal reflux (NPR) with nasal cavity and otologic manifestations of extra-esophageal reflux (EER).

Interestingly, BE is detected in 1-2% of all patients undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). Its incidence is much higher in those with symptomatic GERD (5-15%) and can be found more frequently in those with LPR symptoms (18%). While duration of GERD symptoms correlates with higher likelihood of BE, there is no correlation between severity of GERD symptoms and the propensity to develop BE [1]. Additional risk factors for development of BE are thought to include genetics, central adiposity, cigarette smoking, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and metabolic syndrome [1,4].

In 2018, two concerns arose related to EER patients being seen at the Sinus & Nasal Institute of Florida (SNI) that prompted the initiation of this quality assessment and improvement (QAI) project. First, two silent reflux patients denied being aware of their diagnosis of biopsy-proven BE. Additionally, these two patients had poor compliance with regard to recommended dietary measures, lifestyle changes and medications. Moreover, they did not appreciate the importance of subsequent EGD for BE monitoring. Second, a substantial number of patients with silent reflux who were advised to be see a gastroenterology did not follow through with this recommendation.

The purpose of this communication is to share the findings of our quality assessment and improvement (QAI) program regarding a tertiary rhinology experience with silent reflux and BE. Specifically, this communication is intended to explore the incidence of BE in patients with NPR and to identify the percentage patients who disregarded the importance of their GI referral.

As part of an ongoing QAI program, all new SNI patients who were referred to gastroenterology (GI) in 2017 were identified utilizing an electronic medical record (EMR). The SNI 2017 referral criteria to GIare listed in Table 1. Demographic data, self-reported symptoms, relevant past medical history and BMI related to the clinical suspicion for extra-esophageal reflux were compiled from a standardized intake questionnaire. Information collected included self-reported severity of: Nasal congestion, discolored nasal drainage, post-nasal drainage (PND), duration of PND, symptoms of inhalant allergy (rhino-conjunctivitis), ear fullness, ear clicking, hoarseness, bad breath, drooling, choking on food, worsening asthma, cough, indigestion, heartburn, difficulty swallowing, and pain on swallowing. Past medical history significant for OSA and tobacco use was also recorded. For those who underwent an EGD, procedure findings and pathology reports were reviewed. Histopathology reports confirmed the presence or absence of BE.

For purposes of comparison self-reported EER symptoms as extracted from the standardized rhinology intake questionnaire were grouped based upon three anatomic locations: 1) Nasal cavity/Nasopharynx for NPR; 2) Larynx/Hypo-oropharynx for LPR; 3) Esophagus for GERD. NPR symptoms are: Nasal congestion, discolored nasal drainage, post-nasal drainage (PND), ear fullness and ear clicking. LPR consisted of the following symptoms: Hoarseness, bad breath, drooling, choking on food, worsening asthma, and cough. GERD symptoms consisted of indigestion, heartburn, difficulty swallowing, and pain on swallowing.

Statistical analysis was performed using Jamovi Version 0.9 (The jamovi project 2019 https://www.jamovi.org). For comparing continuous data between two groups, Mann-Whitney U test was used. When comparing categorical data between two groups, a Fisher exact test was applied.

A computerized registry report from our EMR software identified 807 new patients seen at SNI in the year 2017. Of these, 86 (10.7%) were referred to GI in the same year for one or more of the indications listed in Table 1. Of these 86 patients, 48 (55.8%) were female, and the average age was 55 (15-83). Sixty-one patients (70.9%) were referred to GI at the time of their initial visit. Forty-three patients (50%) were seen by a gastroenterologist. Of the 86 patients referred to GI, 79 had completed questionnaires from their initial visit available for review. The presenting symptoms categorized by referred patients, patients who underwent EGD and patients with biopsy-proven BE are shown in Table 2.

Table 1: SNI Criteria for GI Referral. View Table 1

Table 2: Reflux-related presenting symptoms at initial visit. View Table 2

At least one NPR symptom was present in all 79 referred patients with completed questionnaires. Postnasal drip was the most common presenting symptom, reported in 73/79 (92.4%) of all patients referred to gastroenterology and 100% of patients who underwent EGD. Postnasal drip and/or ear fullness/clicking presented in 75/79 (94.9%) of all patients. At least one LPR symptom was present in 69 patients (87.3%) but only 44 patients (55.7%) presented with one or more GERD-specific symptoms. There was no statistical difference in the NPR, LPR or GERD symptoms across three categories of patients: 1) Those referred to GI; 2) Those who underwent EGD or 3) Those with BE.

In the patients with BE, all had NPR symptoms, 4 (66.7%) had presenting LPR symptoms and 4 (66.7%) had presenting GERD symptoms. However, only one patient with BE had significant GERD symptoms and the rest were mild without significant impact on quality of life. In those without BE, 7 (36.8%) had presenting GERD symptoms and 17 (89.5%) had presenting LPR symptoms. When comparing the patients with and without BE, with and without reflux esophagitis and with and without gastritis, there was no significant difference among symptom groups. Regarding presenting symptoms, there was no significant difference between these 79 patients and the 25 patients who had an EGD or the 6 patients with BE. While an indication for proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use at their initial rhinology appointment could not be determined retrospectively, 50% of BE patients and 26.3% of patients without BE were already on a PPI.

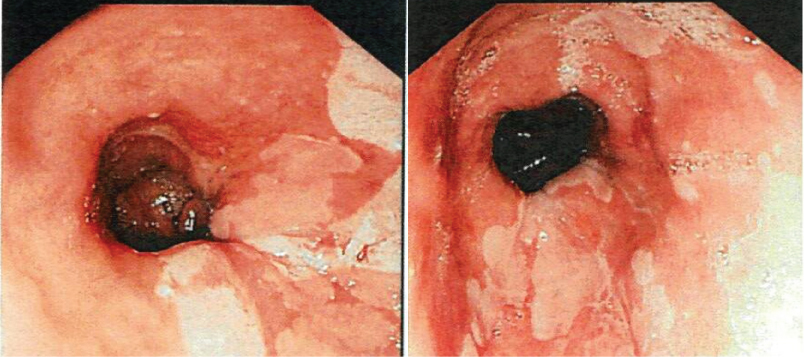

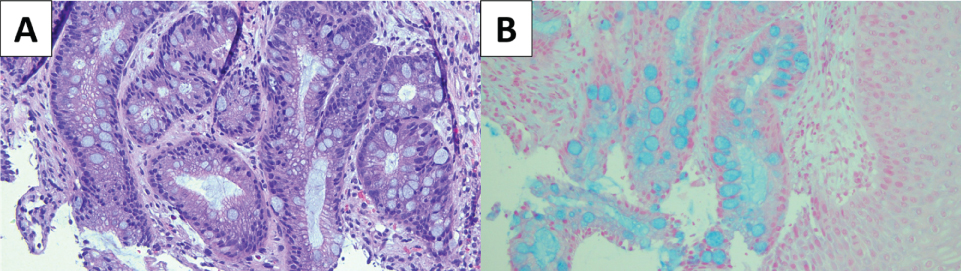

EGD was performed in 25/86 (29.1%). BE was confirmed in 6/25 (24%) patients, (Figure 1 and Figure 2) one of whom had a low-grade dysplasia. None had high grade dysplasia or malignancy. Only 2/6 with BE and 11/19 patients without BE had endoscopic evidence of esophagitis confirmed by pathology. In other words, BE was not always associated with histopathologic evidence of esophagitis. One patient diagnosed with BE was insufficiently aware of this diagnosis until their pathology report was sought out by the referring Rhinologist. Gastritis was confirmed by histopathology in 21/25 (84%) EGD patients. Eight had active gastritis and 13 inactive gastritis. Gastritis was found in all BE patients and in 78.9% of patients without BE.

Figure 1: EGD images demonstrating patches of salmon-colored mucosa extending into the esophagus from the gastroesophageal junction, consistent with intestinal metaplasia.

View Figure 1

Figure 1: EGD images demonstrating patches of salmon-colored mucosa extending into the esophagus from the gastroesophageal junction, consistent with intestinal metaplasia.

View Figure 1

Figure 2: (A) Hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) stained slide of Barrett's esophagus; (B) Alcian blue stain highlights the presence of goblet cells, which are associated with metaplastic intestinal epithelium.

View Figure 2

Figure 2: (A) Hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) stained slide of Barrett's esophagus; (B) Alcian blue stain highlights the presence of goblet cells, which are associated with metaplastic intestinal epithelium.

View Figure 2

None of the patient-reported symptoms were significantly different between the EGD patients with and without biopsy-proven BE.

While rare, EAC carries a poor prognosis with an estimated 5-year survival rate of 17% [5]. As with the rise of BE in the last few decades, the last 30 to 40 years have seen a dramatic increase (300-500%) in EAC. Again, the risk of development of EAC increases when BE is present on the order of 30 to 125- fold as compared to that of the general population [1]. Overall, BE progression to EAC is estimated at 0.1-0.3% annually.

Clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management of BE recommend screening patients with multiple risk factors [4]. Published risk factors for EAC and BE include age over 50, male gender, white race, truncal obesity, history of smoking, family history of BE or EAC, and chronic symptoms of GERD [4]. In our small QAI population, obesity, age, and gender were not detected as risk factors for BE. History of tobacco use, OSA, and infrequent or mild heartburn demonstrated a tendency to be risk factors.

If BE is detected, then additional monitoring is implemented periodically in order to diagnose dysplasia or early malignancy. Endoscopic surveillance of BE has been associated with better outcomes with regard to mortality of EAC [5]. It is worth noting that 50% of patients with BE or EAC do not report chronic reflux symptoms. EGD screening of the general population however is not recommended [4]. It has been previously advised that LPR symptoms should be included as an indication for BE and cancer screening [2].

EER, or silent reflux, is a clinical diagnosis typically based upon presentation of ENT symptoms, findings on physical examination (including naso-pharyngo-laryngoscopy), and tests ordered to rule out other explanations for ENT disease (e.g. CT sinus, allergy test). Confirming the diagnosis of silent reflux is often difficult to assert when the patient never or seldom experiences GI symptoms. Unfortunately, no single test can rule out the existence of silent reflux. To this point, it is proposed that the "lack of response to aggressive acid suppressive therapy combined with normal pH testing off therapy or impedance-pH testing on therapy significantly reduces the likelihood that reflux is a contributing etiology in presenting extra-esophageal symptoms" [6]. Even these steps cannot fully eliminate EER as an explanation for unexplained nasopharyngeal symptoms such as post-nasal drip. This QAI experience supports the concepts that symptomatic NPR, not just LPR and GERD, are associated with BE.

Since silent reflux symptoms tend to be annoying and not life threatening, many patients become readily frustrated and abandon care when they do not see a rapid response to treatment. The diagnosis of silent reflux often challenges the patient's confidence in their physician's diagnostic abilities and treatment plan. Patients are then reluctant to subject themselves to invasive tests to confirm a diagnosis of reflux associated disease. This may help explain the QAI finding that 50% did not follow through with a gastroenterology evaluation.

Postnasal drainage is defined here as the sensation of annoying drainage arising from the nasal airway and draining into the throat. PND is typically attributed to sinonasal inflammatory disease but data suggests that NPR may present as a form of non-allergic rhinitis. In one placebo controlled trial, twice daily proton pump therapy was proven to improve PND among patients without evidence of rhinosinusitis and allergies [7].

This QAI experience highlights a potential association between refractory NPR and BE with or without heartburn. Post-nasal and otologic symptoms were the most common symptoms among those referred for EGD. This QAI project also suggests that smoking history and obstructive sleep apnea are risks for the development of esophagitis and/or BE as previously described elsewhere. Based upon the 25% incidence of BE in this small, self-selected population, we believe that those patients with suspected NPR should be included in the recommendation for EGD. This QAI project suggests that further investigation is necessary before firm conclusions can be drawn.

The drawbacks of this QAI report include its retrospective nature and small sample size and the inconsistent indication for PPIs use in both those patients with and without BE on EGD. PPI use may have been prescribed by patients' internist or referring otolaryngologist for EER symptoms or alternately patients may have self-medicated for symptomatic GERD. Nonetheless there was no difference in PPI use between those with BE and those without BE.

Barrett's esophagus was identified in 24% of self-selected, consecutive new tertiary rhinology patients who underwent EGD. This number is substantially higher than anticipated based upon published data on GERD and LPR. This QAI experience strengthens indications to refer patients to gastroenterology for EGD to rule out BE. Aggravating factors of intermittent mild heartburn, history of tobacco smoking, and OSA approached but did not achieve statistical significance as a risk factor for BE. In those patients with esophagitis, there were a significantly higher number of patients with OSA.

Nearly half of new rhinology patients referred to GI did not follow through with the referral. Explaining the significance of BE as risk factor for EAC may help motivate patients to follow through with a GI referral recommendation. Should the finding of BE exist, improved patient insight is likely to help with patient compliance of treatment and monitoring recommendations.QAI programs such as this are a cornerstone of improving patient care.

We would like to acknowledge both Arthur Berman, DO for providing endoscopic images and Kern Davis, MD for providing pathology images.

This project received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The Authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.