Iron deficiency is one of the most common nutrient deficiencies in the world. The aim of our research was to identify the most common causes of iron deficiency anemia and the associated factors of lifestyle, dietary habits and menstrual cycle.

We selected a random sample of women attending the gynecology department at Tishreen University Hospital and obtained the results of a complete blood count (HCT and HB) CBC for 100 participating women from April 2022 until the end of June 2022. As a result, 67% of women nearly two-thirds were anemic which is considered high for a sample randomly taken from the gynecological clinic in Tishreen university hospital.

Iron deficiency anemia, Syrian women, Causes

Iron deficiency is one of the most common nutrient deficiencies in the world. It can develop into anemia or remain iron deficiency. Hemoglobin concentration and/or erythrocyte volume decreases in iron-deficiency anemia due to insufficient iron availability to produce red blood cells [1].

Iron-deficiency anemia can arise from causes related to chronic blood loss, reduced iron intake or absorption, increased iron demand, or chronic inflammation. Iron-deficiency anemia also occurs in patients with chronic, inflammatory, cancer, or renal disease because inflammatory processes impair the delivery of iron to red cell precursors, regardless of iron stores [2].

Females are particularly vulnerable to iron deficiency and can suffer serious lifelong health consequences if not diagnosed and treated appropriately.

Perimenopausal women presenting with anemia, the most common cause reported is heavy menstrual blood loss. Menstrual disorder accounts for 5%-10% of the women presenting with iron deficiency anemia (IDA) in the perimenopausal age group [3].

In developing counties like India where the nutritional Iron deficiency is very much prevalent in the perimenopausal age group women, menorrhagia acts as an aggravating factor leading to severe anemia. Anemia contributes to increase morbidity and mortality in this age group.

The aim of our research was to identify the most common causes of iron deficiency anemia and the associated factors of lifestyle, dietary habits and menstrual cycle.

We selected a random sample of women attending the Women's Department at Tishreen University Hospital, and obtained the results of a complete blood count (HCT and HB) CBC for 100 participating women from April 2022 until the end of June 2022.

The survey was conducted under the medical ethics applied in Tishreen university hospital and after obtaining the patients consent [4].

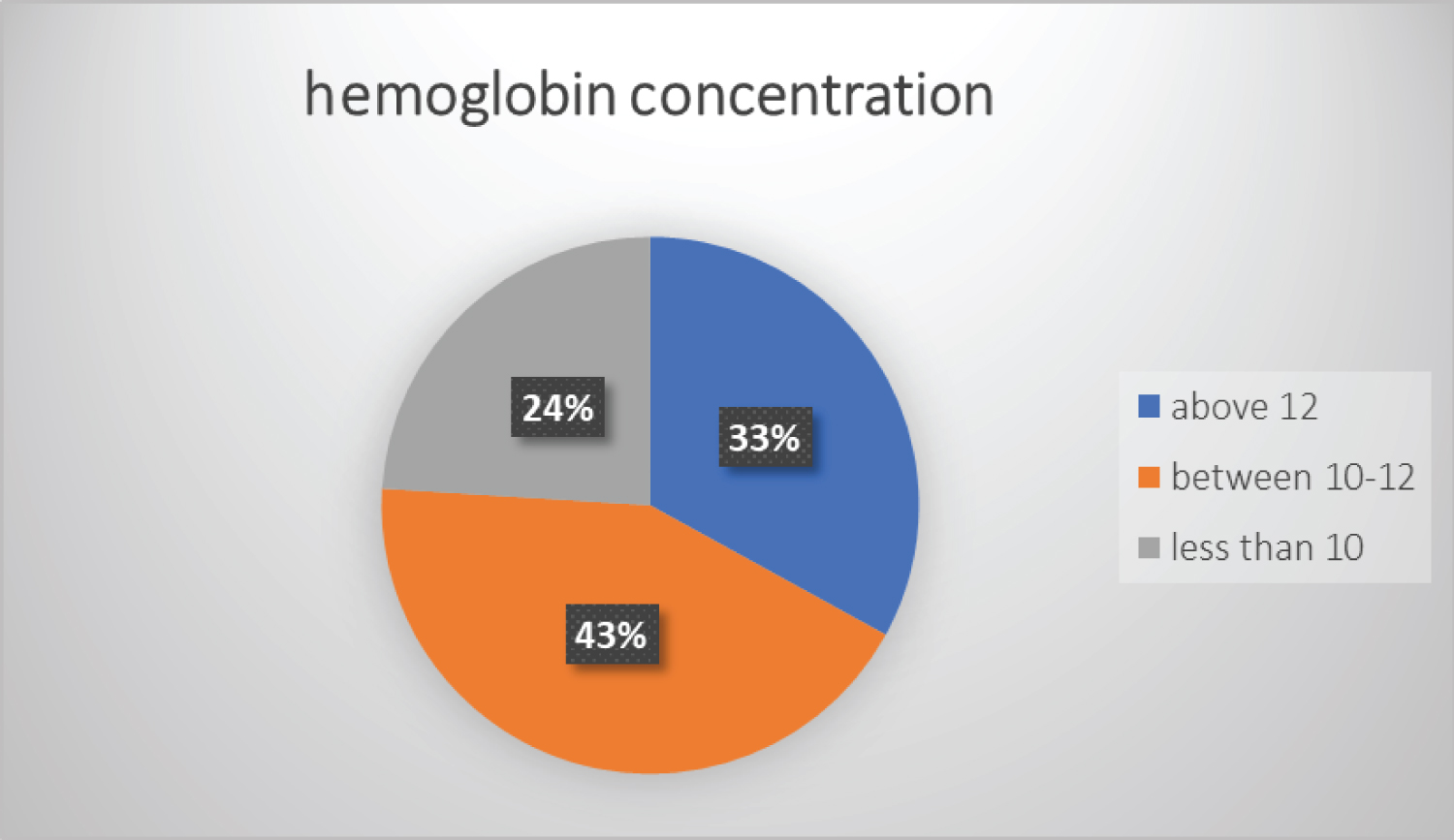

The study sample was divided into 3 categories: Higher than < 10 g\dl , > 12 g\dl , 10-12 g\dl.

According to the WHO criteria for assessing iron-deficiency anemia (less than (12 g/dl)), it was found that the proportion of normal women without iron-deficiency anemia is 33% (haemoglobin above 12 g/dl), while the percentage of women with iron-deficiency anemia is 67% which is two-thirds which is considered high for a sample randomly taken from the gynaecological clinic in Tishreen University Hospital (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Represents the distribution of the study sample according to the concentration of hemoglobin.

View Figure 1

Figure 1: Represents the distribution of the study sample according to the concentration of hemoglobin.

View Figure 1

The study sample was divided into 3 categories: single, married, not pregnant and married, pregnant.

The percentage of single women was 50%, of them 24 had iron deficiency anemia. Surprisingly, 43 out of 50 married women were affected by iron deficiency anemia in our study, and we noticed that 9 pregnant women with iron deficiency anemia out of 13 pregnant women, i.e. 69%, and this percentage calls for emphasizing the necessity of Pregnant women take iron supplements during pregnancy due to the increased need to secure the requirements of the fetus (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Represents the distribution of the study sample according to family status.

View Figure 2

Figure 2: Represents the distribution of the study sample according to family status.

View Figure 2

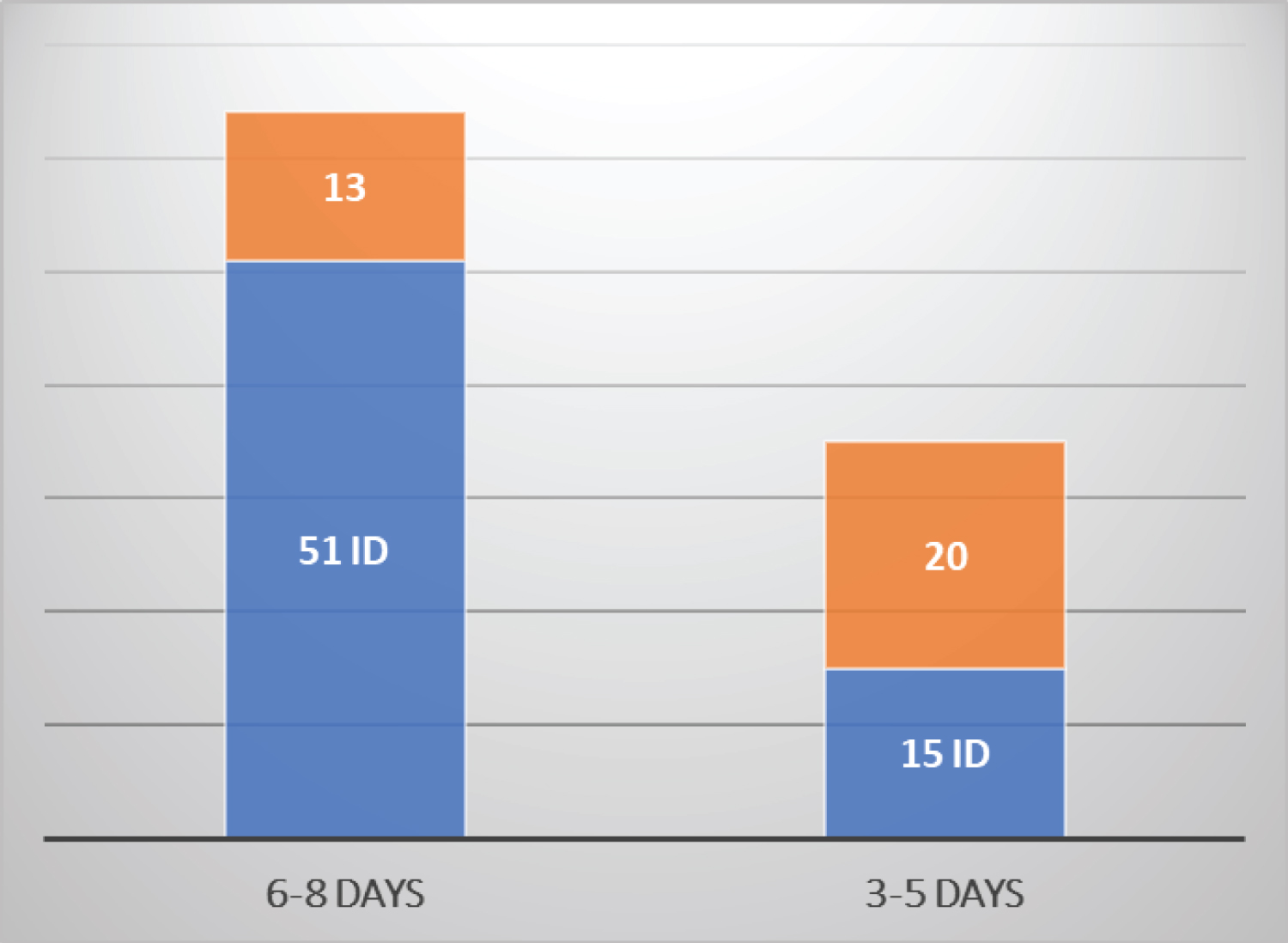

According to the number of days of the menstrual cycle: The study sample was divided into two groups according to the duration of the menstrual cycle: 3-5 days and 6-8 days.

It was found that 15 patients with iron deficiency anemia out of 35 women have a period of 3-5 days, or 42.8%, and 51 patients with iron deficiency anemia out of 64 women whose cycle lasts 6-8 days (80%). This may indicate that the length of the menstrual period is associated with the possibility of iron deficiency anemia, and there was in our study one patient in the menopausal stage (amenorrhea) with uterine fibrosis associated with abnormal bleeding, which explains her iron deficiency anemia (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Represents the distribution of the study sample according to the number of days of the menstrual cycle.

View Figure 3

Figure 3: Represents the distribution of the study sample according to the number of days of the menstrual cycle.

View Figure 3

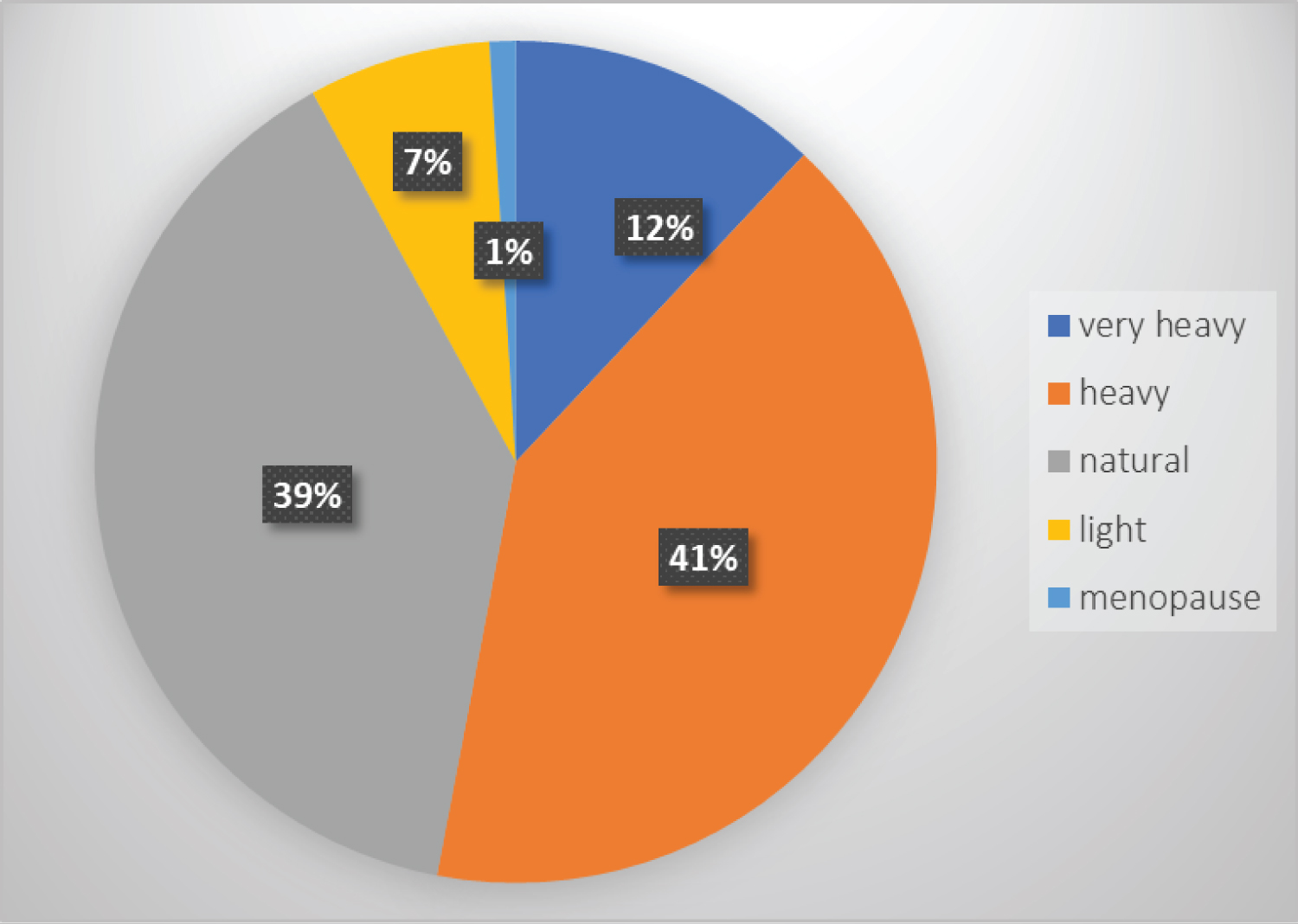

The patients were asked about the intensity of their menstrual flow and were divided into categories:

light 7%, normal 39%, heavy 41%, very heavy 12% in addition to one patient in menopause.

In comparison, 3 out of 7 light-flowing women had iron deficiency anemia (with haemoglobin of 10-12 g/dl).

While those with heavy menstrual cycles, 30 out of 41 suffer from iron deficiency anemia (73%), while those with very heavy menstrual cycles, 12 out of 12 suffer from iron deficiency anemia, knowing that 7 of them have haemoglobin less than 10 g/dl, which is a logical result as Heavy bleeding will lead to the inability of the bone marrow to compensation red blood cells (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Represents the distribution of the study sample according to the abundance of menstrual flow.

View Figure 4

Figure 4: Represents the distribution of the study sample according to the abundance of menstrual flow.

View Figure 4

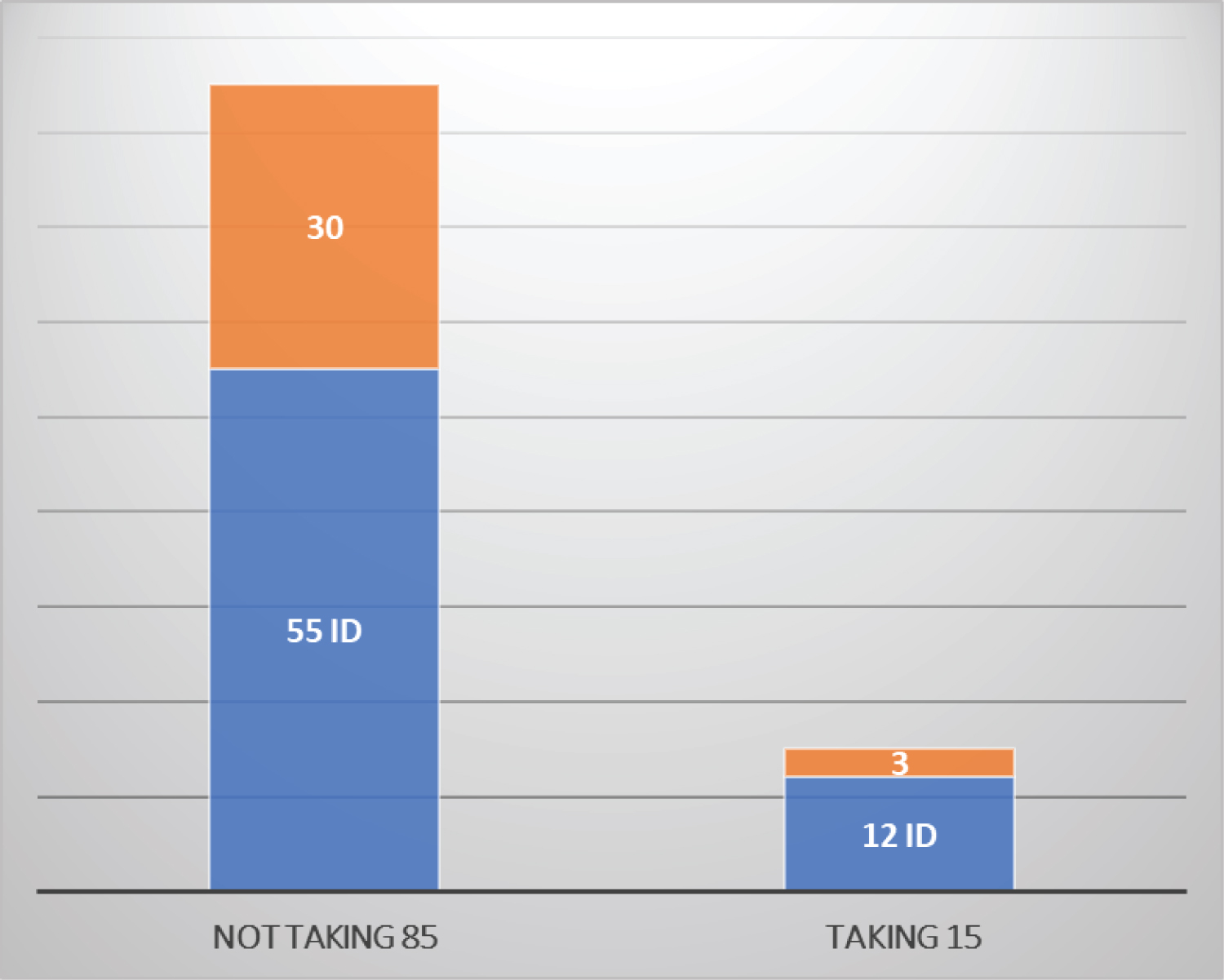

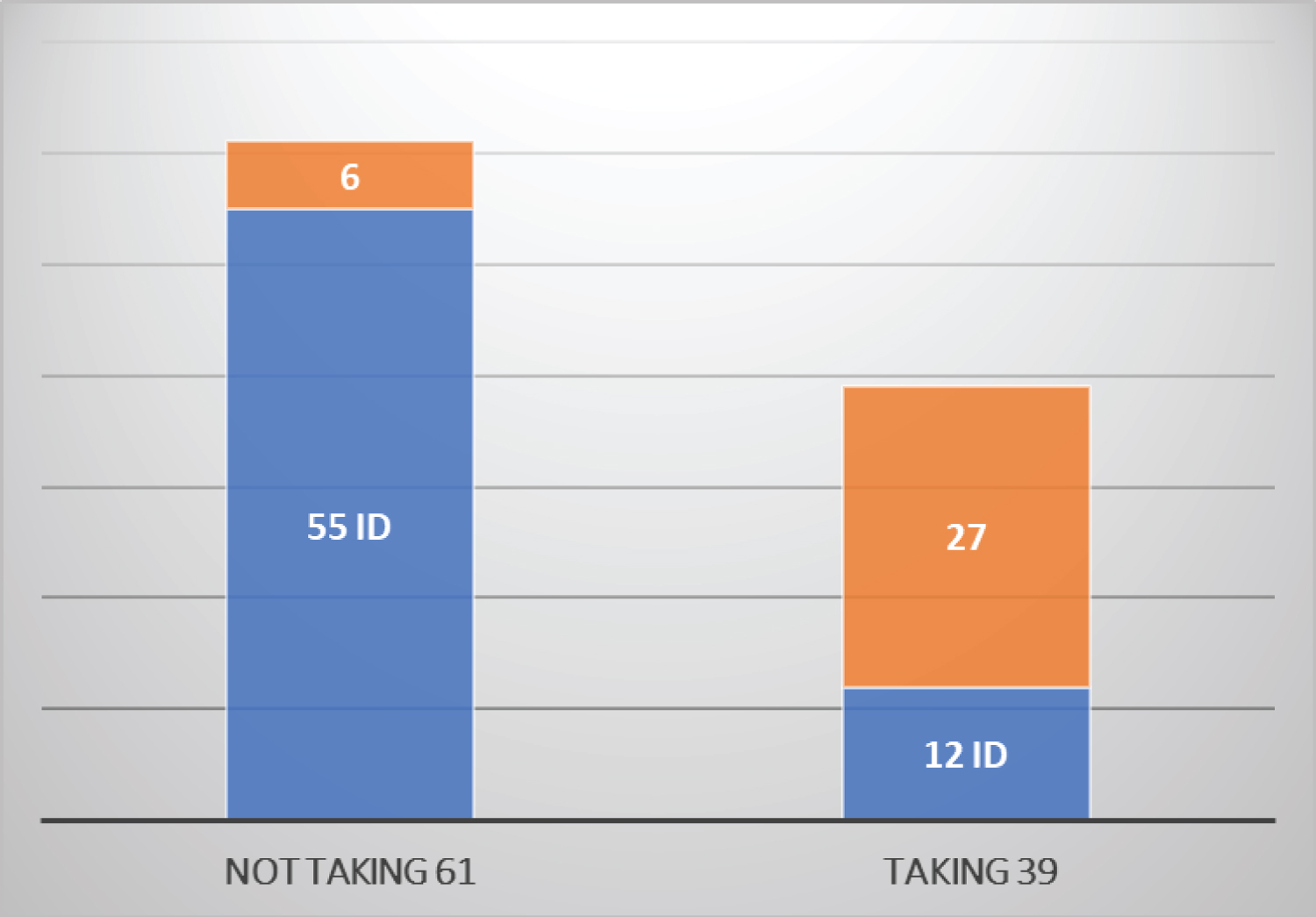

The study sample was divided into two groups according to the intake of antacids, and the percentage of those who are taking antacids was 15%, 12 of them were patients with iron deficiency anemia (80%) and it is considered high. It was found through a study that there is a relationship between taking antacids and ID, as the cause Iron deficiency is a decrease in iron absorption from the gastrointestinal tract with a decrease in gastric acid secretion due to the use of PPIs. As for the percentage of women who do not take antacids, 85% of them were 55 patients suffering from iron deficiency anemia (64%) (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Sample distribution of the study by taking antacids.

View Figure 5

Figure 5: Sample distribution of the study by taking antacids.

View Figure 5

The study sample was divided into two groups according to meat consumption, and the percentage of those who ate meat was 69% of them 42 patients with iron deficiency anemia (i.e. 60%), while the percentage of those who did not eat meat was 31% of them 25 were patients with iron deficiency anemia (i.e. 80%) is considered high.

This diet needs to be discussed, as it should be emphasized that vegetarians should replace meat with iron supplements or replace with iron-rich legumes.

It was noted among the participants that 4 of them suffer from malabsorption (celiac disease) and 3 of them suffer from iron deficiency anemia, this condition does not benefit from diet modification and iron supplements must be given (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Represents the distribution of the study sample according to meat intake.

View Figure 6

Figure 6: Represents the distribution of the study sample according to meat intake.

View Figure 6

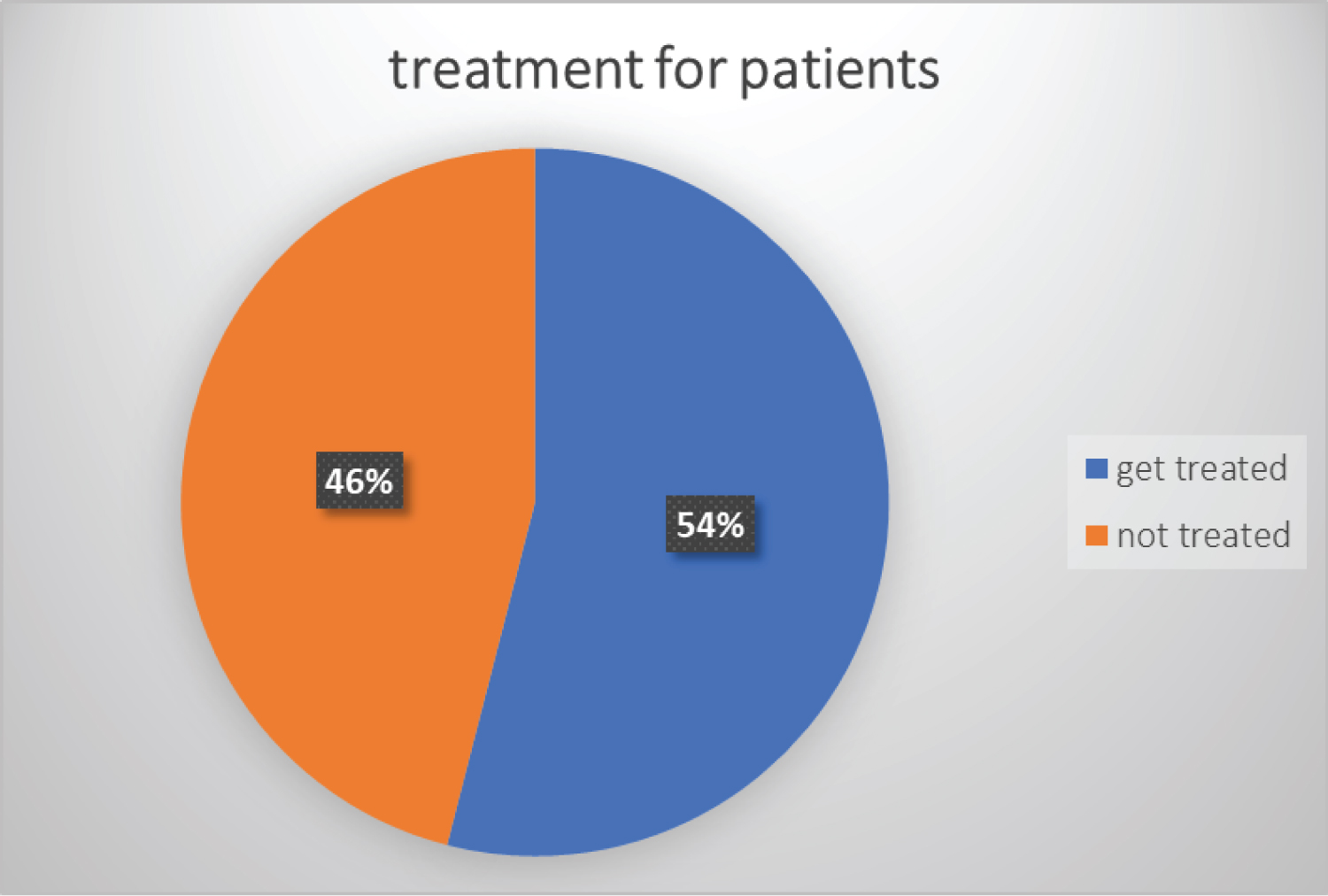

It was found previously that the percentage of women with iron-deficiency anemia was 67%, of them 36 patients were treated (i.e. 54%), 4 patients of them were treated intravenously (their haemoglobin concentration was less than 10 g/dl) and it is considered an emergency case that requires raising iron stores quickly (oral iron needs 4 weeks to take effect), while the number of untreated patients was 31 (46%), This means the need to spread awareness among these patients of the necessity to take iron compounds.

Among the participants, two women were being treated orally although their haemoglobin concentration was higher than 12 g/dl (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Represents the distribution of the study sample according to treatment.

View Figure 7

Figure 7: Represents the distribution of the study sample according to treatment.

View Figure 7

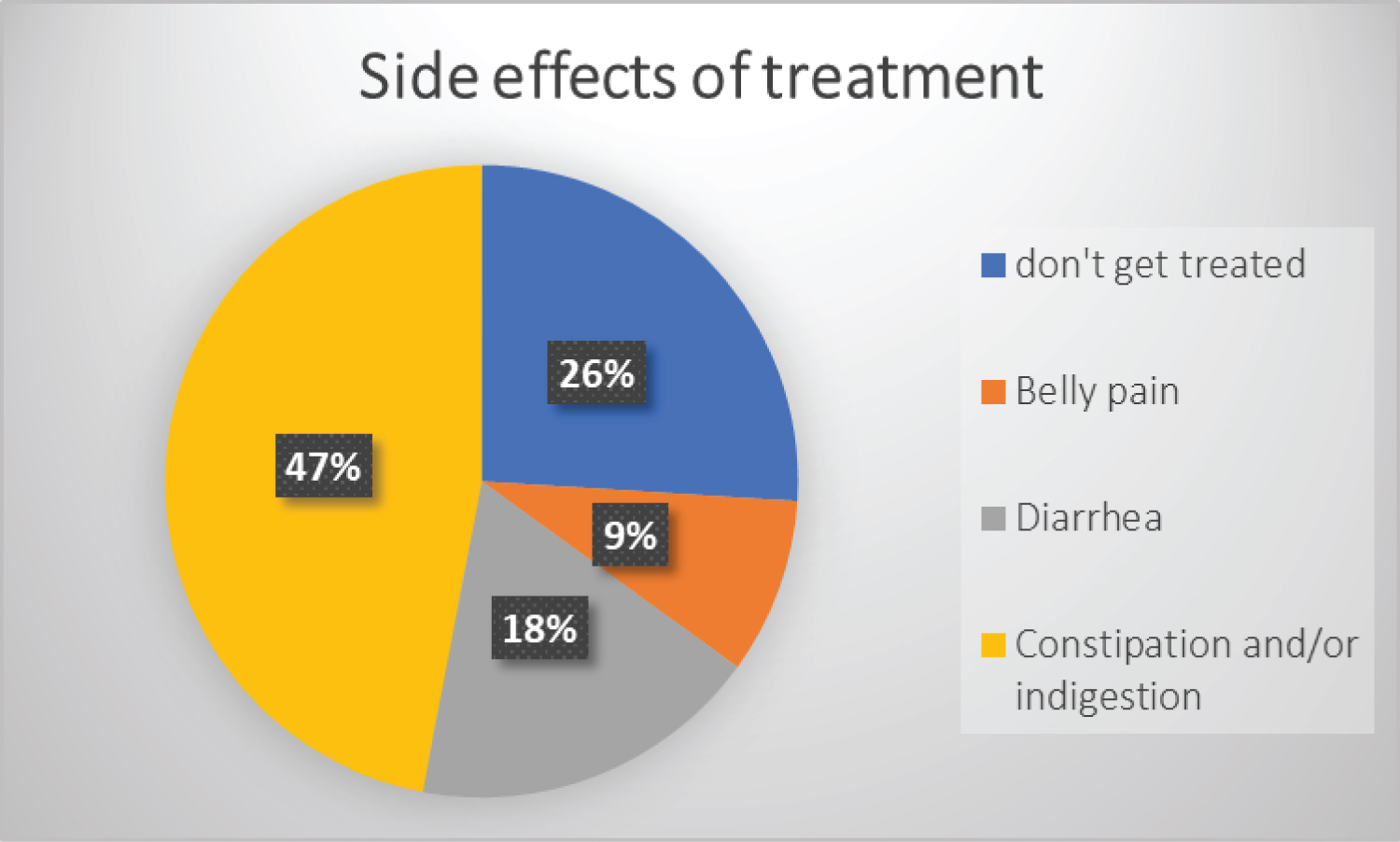

Orally treated patients were divided into 4 categories according to side effects: Constipation and/or indigestion, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, no symptoms.

The number of women suffering from constipation and/or indigestion was 16 patients (47%), the number of women suffering from diarrhoea was 6 patients (18%), who suffered from abdominal pain were 3 patients (9%), and those who did not complain of any symptoms were 9 patients (26%). Oral iron supplements are known to cause constipation and indigestion in high rates in patients (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Represents the distribution of the study sample according to the side effects of treatment.

View Figure 8

Figure 8: Represents the distribution of the study sample according to the side effects of treatment.

View Figure 8

Heavy menstrual bleeding is one of the most important factors contributing to iron deficiency anemia. Measures are needed to alleviate menstrual disorders and improve iron status. Oral contraceptives can be part of a strategy to reduce anemia, particularly for adolescents at high risk of unwanted pregnancies.