Every year millions of children experience being a patient in a hospital setting. When hospitalization is required, many challenges related to coping skills and development face children and families. Examples include being taken out of their typical setting, managing new information, and limited social interactions. This study gathered insights from 203 healthcare professionals (child life specialists, social workers, and counsellors) who work with pediatric patients. Quantitative and qualitative data were used to analyze the needs of both children and families. Perspectives from professionals holding three different roles were compared. The majority of respondents were female child life specialists in the first five years of their career. Their average age was between 25-34 and they are employed in an urban setting. The most prominent needs identified were related to the psychological well-being of the children, followed closely by social and physical needs. Additionally, the most common needs of families from the perspective of pediatric hospital professionals in this study were identified most strongly as psychological needs, with financial and educational needs close behind. Professionals identified a variety of ways these needs are met in the pediatric hospital environment, as well as barriers to address while collaborating to provide optimal child and family support and care in pediatric hospital settings. As more needs of children are identified, professionals can continue to foster coping skills and work to adapt their roles to accommodate and provide resources for both children and families.

Pediatric hospitals, Child needs, Family needs, Child life, Social work, Counseling

As children are hospitalized, they are removed from their social circles and admitted into an often unfamiliar, sterile, and over stimulating environment. Pediatric patients have limited access to the outside world and their typical day-to-day lives spent with peers, at school, and in the comfort of their own home. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, children have become more isolated than ever, especially for those who are at high risk for illness and disease, which may require extended hospital, stays. This research explores the needs and challenges children face in pediatric hospitals through the eyes of child life specialists, social workers, and counsellors. First-hand accounts through survey responses provide detailed information on the needs of children and families, and how these needs are met through targeted professional roles.

An extensive overview of childhood hospitalizations in the United States found over 5.9 million children stayed in a hospital (whether for routine medical and surgical care or for emergencies) in 2012 [1]. This was an increase from the reported 3 million children hospitalized in 2002 [2]. In 2016, KIDS data reported 6.2 pediatric discharges from children's and general hospitals [3]. The Center for Disease Control reported that percentage of individuals in the United States with one or more hospital stay in the past year decreased from 7.8% in 1998, to 7.2% in 2008, and 6.7% in 2018 [4].

There is no doubt due to the recent COVID-19 pandemic, these numbers have been modified. For example, Pelletier, et al. [5] reported a decrease in pediatric admissions in 49 US pediatric hospitals by 45.4% in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, between January 2010 and January 2020, pediatric patients were admitted consistently, with a sharp decrease between March-June of 2020 [5]. Whether the various changes in pediatric patients are due to resources and availability of medical care or changes in medical conditions, overall, children are consistently being housed and taken care of in hospital settings. These stays include those who were admitted into hospitals overnight for at least one night.

In total, about half of all child hospitalizations are due to children having medical complexities or children that are faced with multiple medical issues at once [6]. A majority of these hospitalizations were found to have lasted longer than 10 days in hospitals, accounting for 62% of the hospital's costs and resources spent on the care of these children [6]. Children are an important population for the hospitals and longer stays can have many tolls on the children and the families. Their challenges need to be accounted for during their time spent in pediatric medical facilities.

A qualitative study conducted by Adistie, Lumbantobing, and Maryam [7] examined the needs of terminally ill children through interviews with nurses and parents of the children. The results of the study were broken down into three groups: biological needs, psychological needs, social and spiritual needs [7]. To fulfil the basic biological needs, therapy programs, enhancing the comfort of the child, and minimizing infection prevention were the most prominent needs. Age-appropriate information for the child and parents and involvement of the parents in medical care were crucial to the psychological needs of the child.

The social needs such as play, meeting the demands of school, and additional social support were important as well, along with the need for spiritual guidance [7]. Although the researchers mainly addressed children with terminal illnesses, it is important to note the needs of these children typically included those who stayed in hospitals for extended periods of time. A significant part of children feeling comfortable in the hospital is the interaction, connection, and experiences they have with their doctor(s) and other healthcare staff.

Another study examined what information children wanted to know from their healthcare professionals. The children wanted information directly from their healthcare professionals and not just from their parents; however, many times they did not understand what the healthcare professionals were telling them [8]. Simple explanations from doctors helped the children to feel included and more understood. It is essential the information shared with pediatric patients is tailored to a child's need and understanding [8]. If the child can learn directly about their medical condition and actively participate in their care plan, it helps them to feel safer and content with their hospital experience.

The existing research only begins to scratch the surface of the needs facing hospitalized children around the country. It is important to recognize the number of children being admitted into hospitals each year and consider the needs they have during their stay. It takes a team to aid children and families during the hospital experience. Therefore, this study examined how child life specialists, social workers, and counsellors play a role in addressing and meeting the needs of children and their families, knowing they are instrumental in the hands-on care of the child.

This article highlights the results of a study focused on gaining insights about defining the needs of children in pediatric hospitals through the lens of various professionals working in hospital settings. The professional experiences in their respective fields with pediatric patients are examined. Results of the study are utilized to inform families, professionals in social work, counseling, and child life fields, as well as hospital administrators, and pre-professionals in the various fields.

Child life specialists, social workers, counsellors, and other pediatric healthcare professionals were invited to participate in an online survey via email and phone calls. A total of 203 pediatric professionals participated in the survey from seven geographical regions around the United States.

After completing a comprehensive literature review about issues impacting children in pediatric hospitals including their needs and supports for families, an original survey titled Meeting the Needs of Children in Pediatric Hospitals consisting of twenty-seven questions was developed. Upon IRB (Institutional Review Board) approval, the researchers utilized a list of all pediatric hospitals in the United States from the Children's Hospital Association, available online at https://www.childrenshospitals.org/directories/hospital-directory. After constructing a detailed list of contact information for each facility to reach child life specialists, social workers, and counsellors, the survey was constructed on Survey Monkey. The survey link at https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/PediHospital was distributed online to professionals on the contact list, inviting them to participate in the research project.

After survey collection was complete, the researchers analyzed the data utilizing the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) to analyze quantitative data, and thematic analysis was utilized to examine qualitative data. A detailed analysis of the data from 203 target subject surveys took place, including descriptive statistics and percentages utilizing a comparative analysis.

Additionally, the open-ended responses were reviewed and divided into themes. The process of coding the data took place by making notes of initial themes through the process of memoing, followed by the completion of summary statements. The authors coded text within the themes to determine emerging specific ideas regarding issues facing children and families in the pediatric hospital environment.

As stated previously, 203 professionals initially participated in this study. Of the 203 points of data that were analyzed during this investigation, there were 178 child life specialists (87.6%), 16 social workers (7.88%), two counsellors (0.98%), two music therapists (0.98%), two art therapists (0.98%), one administrator (0.49%), and one hospital-based teacher (0.50%) who participated in this study. The participants ranged in age from 18-24 to 65 plus, with over half of the pediatric hospital professionals being 25-34 years-old (56.65%). Regarding years of experience in their current professional role as a child life specialist, social worker, or counsellor, the total years ranged from 0-5 to 46-50 years. Near half of the professionals had worked 0-5 years in their prospective profession (47.78%). Near all of those that responded to this study reported their race or ethnicity as White (94.03%). Specific details of the participant demographics are provided in Table 1.

Table 1: Participant demographics. View Table 1

In addition to demographic data about their gender, age, race/ethnicity, years of experience, and professional roles, the survey also asked about which geographical area participants lived in the United States, and how to describe their employment setting. Of the seven geographical regions across the United States, the most represented group was the Midwest, with 71 (35.32%) from this area. Southwest was the next area with 42 participants (20.90%), followed by 29 Southeast professionals (14.43%), Rocky Mountains with 29 (14.43%), Pacific Coastal with 15 (7.46%), Mid-Atlantic at 12 (5.97%), and finally New England with three (1.49%). Over half of the study participants reported the location of their employment as urban (65.15%), followed by suburban (26.26%) and rural (8.59%). In addition, the majority were employed by the hospital (92.57%), with some working for the school district or an outside network.

When questioned about the specific units professionals in this study work in, the most common response was General (37.13%), followed by Emergency Department (36.14%), Oncology (28.22%), Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (29.21%), Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (11.88%), Transplant (9.90%), and Rehabilitation (7.43%). Other units described by professionals in pediatric hospitals included Neurology, Outpatient Clinics, Surgery, Radiology, Burn Clinics, Labor and Delivery, Eating Disorders and Psychology, and an Outside Counseling Agency.

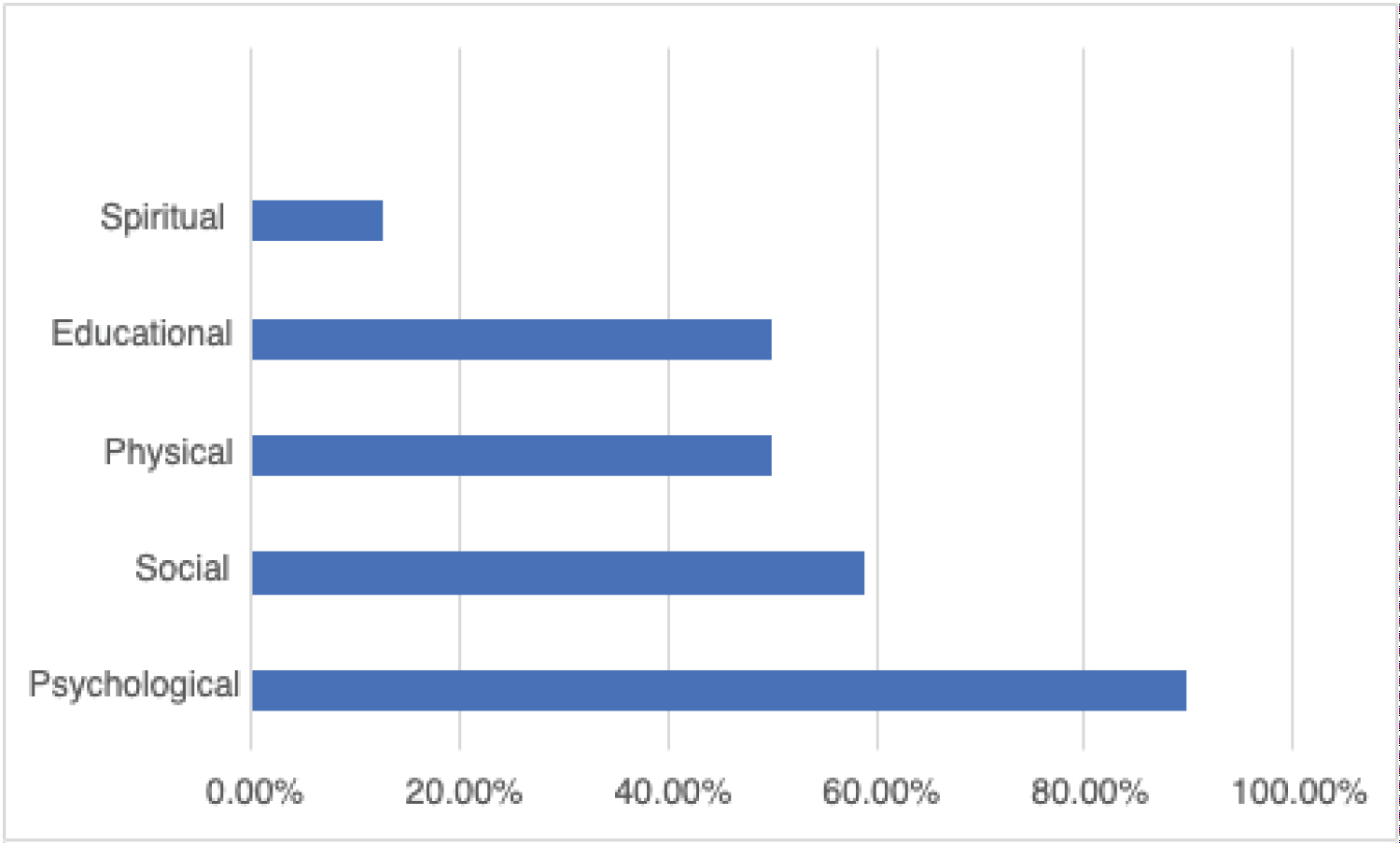

Five major themes emerged from participants' discussions of the needs of children in pediatric hospitals. These needs, including the psychological, social, physical, educational, and spiritual care needs of children, are discussed in detail below. Figure 1 outlines the five needs of children as they were identified by study participants.

Figure 1: Most important needs of children.

View Figure 1

Figure 1: Most important needs of children.

View Figure 1

Psychological needs: The majority of the participants in this study (90.15%) identified psychological needs as the most important need children face in pediatric hospitals. To address the psychological needs of children while they are in the hospital, professionals supported children through teaching coping skills (93.60%), playing and using games to address needs (87.19%), addressing grief and bereavement (78.33%), and providing counsel to the child (40.39%).

One child life specialist shared about helping children through positive coping skills during a variety of procedures that take place during medical care. In addition, this participant also stated, "I help reduce psychological anxiety, distress, and pain through various therapeutic and non-pharmacological interventions." Other comments describe how to address psychological needs as the professional works diligently to "facilitate coping through play-based intention and supportive presence." Yet another important perspective was stated

...we have a unique understanding of a child's developmental stage, understanding, and interpretation of information. We use education to promote age-appropriate information/appropriate choices over medical care to empower children. We use play to help children understand and process hospitalization/trauma, as well as normalize the environment and allow for an outlet of expression. Counsel is seen through the empathetic engagement and validation of feelings that a child life specialist provides...

Another child life specialist explained

Mental health care within the hospital system is incredibly siloed. Our system is overburdened to an extreme degree and very often we are not meeting the psychological needs of our patients due to limited services. We work to improve this every day.

Social needs: Over half of the participants in this study (59.11%) identified social needs as the most important need children face in pediatric hospitals. To address the social needs of children while they are in the hospital, participants supported children through playing games (52.53%), teaching communication skills (11.11%), and setting up virtual visits with friends and families (11.11%).

One professional explained the role they play in the life of a child while the child is in the hospital, "As a child life specialist, I aim to keep the child connected to their world outside the hospital. This means providing their school with support, providing information on community groups for diagnosis support, etc." Another pediatric hospital professional shared, "...it is important for a child to feel a connection; both with their medical staff, family members, and life outside the hospital. In my role/unit, I primarily use play/games to build rapport and foster connection." Specifically focusing on the role of a school social worker and supporting social needs, the following statement was reported, "we write individual goals or speak closely with family to identify needs of children and families."

Physical needs: Half of the participants in this study (50.25%) identified physical needs as the most important need children face in pediatric hospitals. To address the physical needs of children while they are in the hospital, participants supported children through movement including walking, crawling, and mobility support (53.50%), basic hygiene tasks (23.50%), feeding (15.00%), as well as engaging in play and through medication compliance such as teaching pill swallowing and techniques for liquid medication. Half of the study responses stated that supporting physical needs did not apply to them in their professional roles in the pediatric setting.

"I respond to educate patients and families about physical illness and procedures and upcoming procedures" is the way one professional described how they address the support of physical needs of pediatric patients. Another shared, "If a child needs to get up and walk around post-surgery, I would offer something fun to do to try and help accomplish that goal." One participant described how the physical needs of children in their program at the hospital were supported by the child life specialist

I assist with distraction and give challenges to post-op medical surgical and burn patients. This can include walking challenges, physical activities, scavenger hunts, and encouraging walks/wheelchair or wagon rides off the unit to encourage walking and movement in the healing garden. I also encourage movement and participation to promote movement and stretching during burn hydrotherapy (dressing changes). I do this to promote play and activity while also promoting physical movement as a means of normalization.

Educational needs: Of the professionals that completed this survey, 33.00% stated the most important need of children in hospitals centered on educational needs. When addressing the educational needs of children during their hospital stay, one professional described their role as "connecting families with community resources." Additionally, another response captures the focus of addressing needs of families as they address educational concerns and needs, "when they need the support and resources and... follow through." One child life specialist stated the value of addressing educational needs as well as the professionals in the hospital environment providing education themselves during challenging times, "I also provide education and support during end-of-life situations." Another child life specialist provided an example of utilizing education to teach a child how to swallow pills

An example may be medication compliance - if the child is refusing to take medication, the child life specialist may work one on one with that child and parent to address the fear and work on physically practicing pill swallowing utilizing M&Ms. For physical needs that require immediate care (lacerations, broken bones), we collaborate with other healthcare professions to provide education, distraction, and coping support in the same moment that the medical team is repairing the need.

Spiritual care needs: In this study, 12.81% of pediatric hospital professionals believed that spiritual care needs were the most important needs of children in pediatric hospitals. When asked about how these needs are met, the majority of individuals (60.91%) stated that this area did not apply to their professional role in the pediatric hospital setting. Those that did address spiritual care needs did so through fostering personal growth (19.80%), leading grounding exercises (12.69%) and through prayer (3.55%).

Several participants mentioned collaboration with others to support the spiritual care needs of children in the hospital. Many stated referring patients to the designated chaplain or spiritual care department. One professional commented

Due to [the hospital] being a state-run institution, we are encouraged to refrain from spiritual conversations in order to remain sensitive to different cultural spiritual beliefs. However, if a child/family brings up religion first, I am able to base my supportive intervention around their spiritual beliefs. In end-of-life situations/trauma/in-patient stays, if the family speaks of religion, we will offer to contact pastoral services for their support.

Other child life specialists mentioned that even if they cannot support or bring the families faith into the conversation, the child can be supported spiritually through meditation or other reflective techniques to aid in the medical care process.

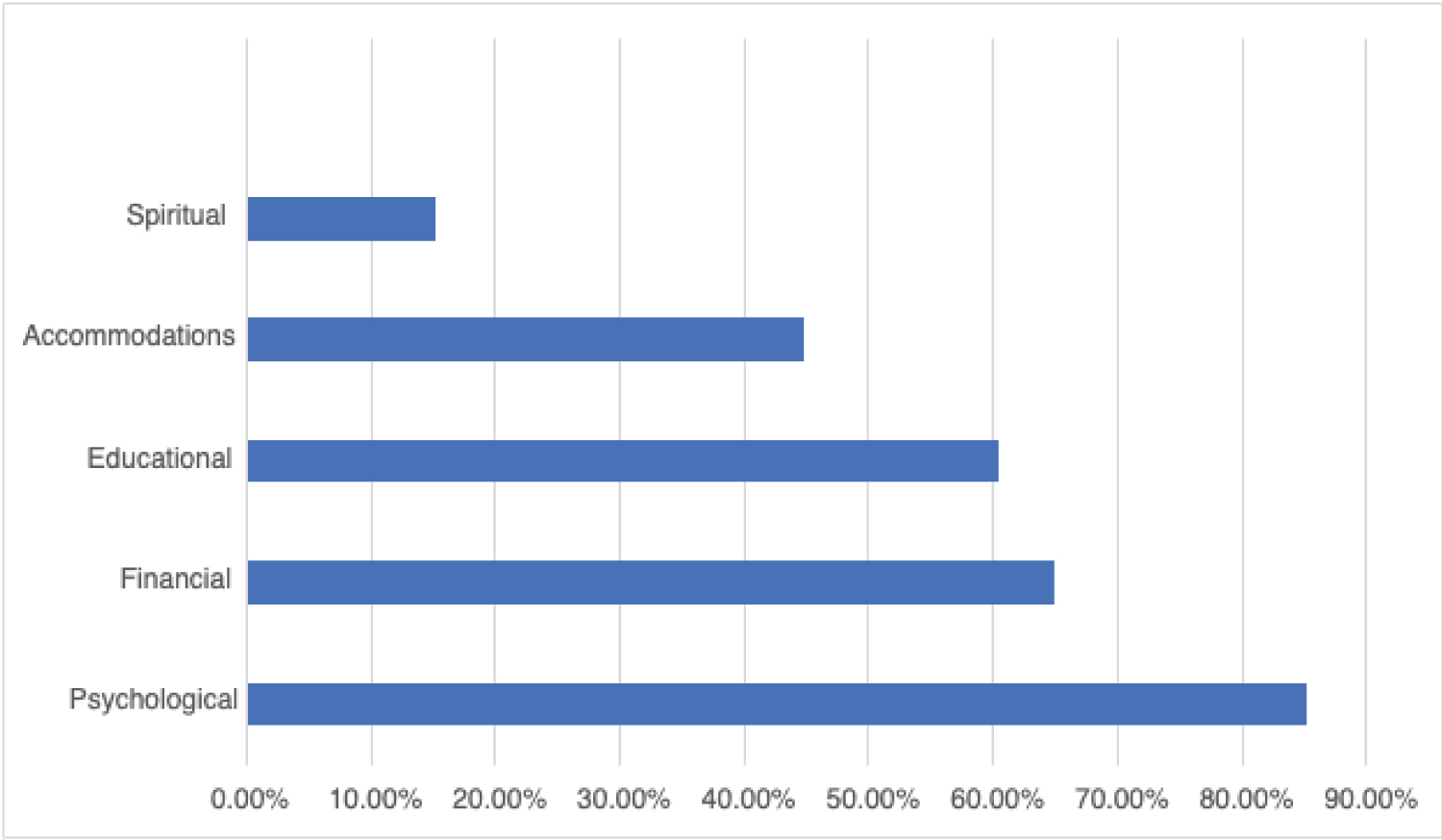

After participants shared their perspectives about the needs of children in the hospital setting, the focus was then shifted to the needs of the entire family unit. Psychological needs were ranked as the most important need of families (85.22%), followed by financial needs (65.02%), educational needs (60.59%), accommodations (44.82%), and spiritual care (15.27%). Other responses included social needs, sibling support, and community needs. Figure 2 outlines the needs of families as they were identified by study participants.

Figure 2: Most important needs of families.

View Figure 2

Figure 2: Most important needs of families.

View Figure 2

The COVID-19 pandemic had significant impacts on hospitalized children and provided new insight into the significance of children interacting with one another in relationship to the healing process. One of the biggest challenges expressed was difficulty making connections between other children/families due to the isolation. One child life specialist said

It has been challenging for patients as well as caregivers to not have as many joint opportunities to meet and gather (play groups, parent rooms) - where kids can feel like they gain support from other kids in the hospital "just like them." It is motivating for a kid to get out of bed to go attend a play group in a playroom down the hall. Movement is important to their physical health and personal well-being. With fewer opportunities to leave their room, there is less motivation to get out of bed.

Along with the isolation came psychological difficulties. One professional noted the following regarding the mental health of young patients

Increase in suicidal teens is something I deal with on a repeated basis. Many are engaged in therapy but that doesn't seem to be enough support. We would love additional programs/supports they could access to help with normalizing feelings, re-enforcing coping skills, and providing education to families.

Children were not the only ones affected by COVID-19 protocol and precautions in the hospitals. One child life specialist said, "COVID has created difficulty for parents as well in regard to isolation and connection. In previous work in outpatient oncology, many parents would connect in the waiting rooms and share their experiences. They could validate one another and offer ideas/mentorship/support."

Child life specialists, social workers, and counsellors discussed the challenges children face in hospitals and how patient and family needs are addressed through their specific roles. The needs for both families and children were examined separately, and the healthcare professionals commented on how they supported the variety of ways they addressed these needs. Most professionals working in these roles were child life specialists in the first 5 years of their career. These early professionals were most commonly employed directly by the hospital network. Themes emerged as the most significant children and family care which are psychological, social, educational, and financial.

After examining all the needs discussed, psychological needs emerged as the most prominent for both patients and their families. Teaching and coping skills were the most common ways professionals addressed psychological needs. Mental health disparities among children were addressed by a few professionals. Social needs were the second most significant for children. A vast majority of social needs were met through the use of games followed by teaching patients about communication skills and setting up virtual visits with family and friends outside of the hospital. As stated, since the beginning of the pandemic, social isolation has increased for everyone, but especially for those in pediatric hospitals. The social needs facing children now are greater than ever. Child life specialists in this study aimed to keep outside communication open between patients and their families.

Among the second highest needs for the families were financial and educational. From prior research, continuing to work on meeting the informational and educational needs of patients and their families should be considered. Lambert, Glacken and McCarron [8] addressed children and families not understanding the medical information they are given. Age-appropriate information used for children to cope with the psychological tolls they may face was addressed by Adistie, Lumbantobing and Maryam [7]. Families are not only in psychological distress when they arrive at the hospital with their child, they may also need to have the information to take home and be able to educate themselves on issues facing their child, so they can help the child understand as well.

Children are being hospitalized consistently throughout the United States, and we will persist as we continue to fight COVID-19 pandemic. As children continue to be hospitalized and as stay length may increase, the needs of children and families may become challenging to meet. Professionals in the roles of child life specialists, social workers, and counsellors need to be able to identify the needs and do what they can in their role to advocate for the family. Gold, et al. [6] points out those children are faced with multiple complexities when they arrive at the hospital, and this study shows that. This is important to recognize and note so all pediatric professionals can be aware of the support children might need outside of their routine medical care.

Appropriately 35.86% of the data collected was representative of professionals from Midwest pediatric hospitals. Future studies should consider examining the differences between the needs of children and how they are met in different regions across the United States. Most of the participants were females working in child life roles. To gain more insight, expanding the data to include a broader gender and diverse role pool should be considered.

The authors wish to sincerely thank the professionals from pediatric hospitals across the United States that chose to participate in this study.

The data collected in this study, as well as the lessons learned provide insights for professionals in pediatric hospital environments. With psychological and social needs of children being designated at the most commonly identified with this population, it is important to focus on the existing skills and knowledge of various professionals to address these needs. A focus on the curriculum and field experiences pre-professionals experience prior to employment in pediatric hospitals may offer insights about existing learning opportunities and optimal training options to best prepare these professionals to fully support the psychological and social needs of children.