This study was conducted to reflect the clinical profile of patients presented to Emergency department (ED) with complications of acute coronary syndrome in developing country like India. This prospective cohort study was conducted in a cohort of 50 patients' with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). They were followed up an over duration of three months for the outcome during hospitalization. Male; smoker; age > 60 years; hypertension were representative risk factors for this cohort. More than 96% of patients presented with chest pain, mostly in early morning hours. Thrombolysis was given to 46 patients (92%); and out of these, 21 (42%) patients succumbed to death. This study emphasised mainly on health education on adoption of health lifestyles and symptoms; early access to health care algorithm control of hypertension and related morbidities. The study has also tried to address need of policy ramification for strengthening for Non-communicable diseases in developing countries.

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the leading cause of mortality in India attributing to a quarter of all mortality [1]. Despite spectacular progress in disease prevention, detection and treatment over the last three decades; more than 80% of CVD deaths are caused by Ischemic heart disease and stroke [1,2]. Considering early mortality rate from acute myocardial infarct (AMI) (30-day), still death from CVD Carries higher burden [1-4]. Interestingly, more than half of these deaths were occurring before the diseased individual reaching the the hospital [3-6].

Although the mortality rate after admission for acute coronary diseases has declined by 30% over past two decades [7-9], approximately 1 in every 25 patients survived the initial hospitalization dies in the first year after AMI [2,10]. In several patients, progressive nature of heart failure leading to ischemic cardiomyopathy reflects the progressive nature of underlying coronary artery disease [7,9]. Thus, identification of of patients at risk of developing heart future heart failure after first myocardial infarct and detection of the extent of future heart failure is the corner stone of secondary prevention strategies. This might help in prospective for treatment in reducing morbidity and mortality from heart failure following AMI [10,11]. Coronary heart disease is the greatest cause of death among women as well; mainly affecting women younger than 45 years [1,12,13]. Developing countries are trying to tackle the cardiac events especially in government medical colleges and instution, which serves to cater needy population of the strata. This study represents brief snapshot of population presenting of complications of acute coronary syndromes. It also attempts to evaluate clinical profile of patients presenting with complications of acute coronary syndrome in developing country like India.

This prospective cohort study was conducted over duration of three months in one of the government medical college in India. Government medical college in India provide free medical care. Medical college was chosen considering patient flow, facilities available required for basic & advanced cardiac care and being tertiary health care access facility catering all strata of population. As this study was part of Master's project completion, short time frame of 3 months follow up of patient was decided. Purposive sampling technique was used to recruit 50 patients, fitting into inclusion and exclusion criteria. Considering that subsidised medical facilities were available at the study site, study population was presumed to be representative of population of India. This population cohort has given glimpse of snapshot of ACS cases presenting with complications. Ethical committees' approval was taken before conducting the study.

Inclusion criteria for patient recruitment: Cohort of hospitalised ACS patients.

Exclusion criteria: Patient and/or their relatives who declined to give consent and other related information.

Enrolled patients were followed up till outcome of their admission; minimum planned duration of follow up was for 3 months. All department residents were briefed about study protocols and inclusion criteria; they helped to recruit patients in this study. Patient's records were assessed by primary team members. In view of no direct patient contact or intervention was involved, only oral consent was taken either from patient and/or patient's next of Kin (NOK). Ethical committee approved this as primary medical team was involved in the process. Patient, their NOK were approached, updated about research objectives and purpose of research. It was explained to them that patient's personal identifiers such as name; phone number and/or address will not be used anywhere. Confidentiality and privacy were assured to them. Primary team members completed the baseline and follow-up survey form. Survey forms were reviewed for ensuring data validation by principal investigator. Complication included cardiac arrhythmia, ventricular tachycardia, heart block, cardiogenic shock and ventricular tachycardia. Outcome included death survived. Treatment options were classified under thrombolysis, LMWH, Inotropes, Mechanical Ventilation.

Data was analysed with help of SPSS. Baseline information about modifiable and non-modifiable risk factor was collected through predefined and pretested questionnaire. Modifiable risk factor included addiction details such as smoking, tobacco usages. Non-modifiable risk factors included gender, age, family history, etc. Clinical profile of all these patients was documented. Complications were classified as ARF, pulmonary oedema, arrhythmia, ICH/stroke, treatment modalities and outcome of admission were documented for all patients.

In cohort of 50 patients, 66% were males. While 94% patients were above age of 50 years, only 6% of patients were below 50 years of age, while 38% of patients' ≥ 60 years and remaining 26% between 50-59 years of age. Mean age of this cohort was 63 (± 10.7) years. Out of this cohort of 50, 24% patients were obese. More than 40% (21) of patients were smokers while 10 cases (20%) were tobacco chewers (20%). Out of those 21 Smoker, 17 (80%) reported smoking more than 20 packets year. Only one patient has reported history of Ischaemic stroke while 35 (70%) patients had hypertension: and 16 (30%) diabetes.

On reviewing prophylaxis regimens, only 20% (10) patients were taking aspirin; 52% (26) on ACE (Angiotensin-converting-enzyme) inhibitors and 40% (20) were on Beta(B)-blocker. Thirteen patients were on prophylactics Aspirin. Considering past history related to cardiovascular risk factors, 70% (35) had Hypertension and 32% (16) had Diabetes Mellitus. Evaluating past history of cohort of these patients, 24% reported past history of IHD (Ischaemic Heart disease) and only one patient with past history of Ischaemic stroke. Only 4 cases out of 50 (8%) reported family history of IHD; 32% (16) of hypertension (HTN) and 12% (6) of Diabetes Mellitus (DM). Before this cardiac event, half of patient had already reported exposure to precipitating factors such as vigorous exercise, emotional stress or a medical or surgical illness.

Majority of patients (96%) presented with typical chest pain of acute myocardial infarction, while 90% were having perspiration, 28% patients had breathlessness, 24% presented with nausea/vomiting, 14% with giddiness, 12% with palpitation with remaining 7% presenting with other nonspecific symptoms (drowsiness, unconsciousness, etc.). Most patients (98%) reported Gabharaman (being scared!) on presentation to hospitals; rest reported Chest pain (92%), perspiration (88%) and nausea (60%). Small proportion of cases presented with vomiting (24%), dizziness (14%) and abdominal pain (10%). Peak incidence of onset of symptoms was in morning hours (6 am in morning to 12 Noon). Very few patients (8/50) visited hospital within 6 hours of onset of symptoms and most patients (28/50) visited within 6-12 hours. Majority of patients (82%) presented with complications within 12 hours from onset of chest pain while 16% presented with complications between 12 to 24 hours and 2% presented after 24 hours of onset of chest pain. Half of patients (26/50) reported only one complication, 19 patients (38%) ≥ 2 complications while 5 patients (10%) reported nil complications. MTD to access health care services was significantly associated with complication presentations. Past history of IHD and Aspirin prophylaxis were major protective factors against complication of ACS.

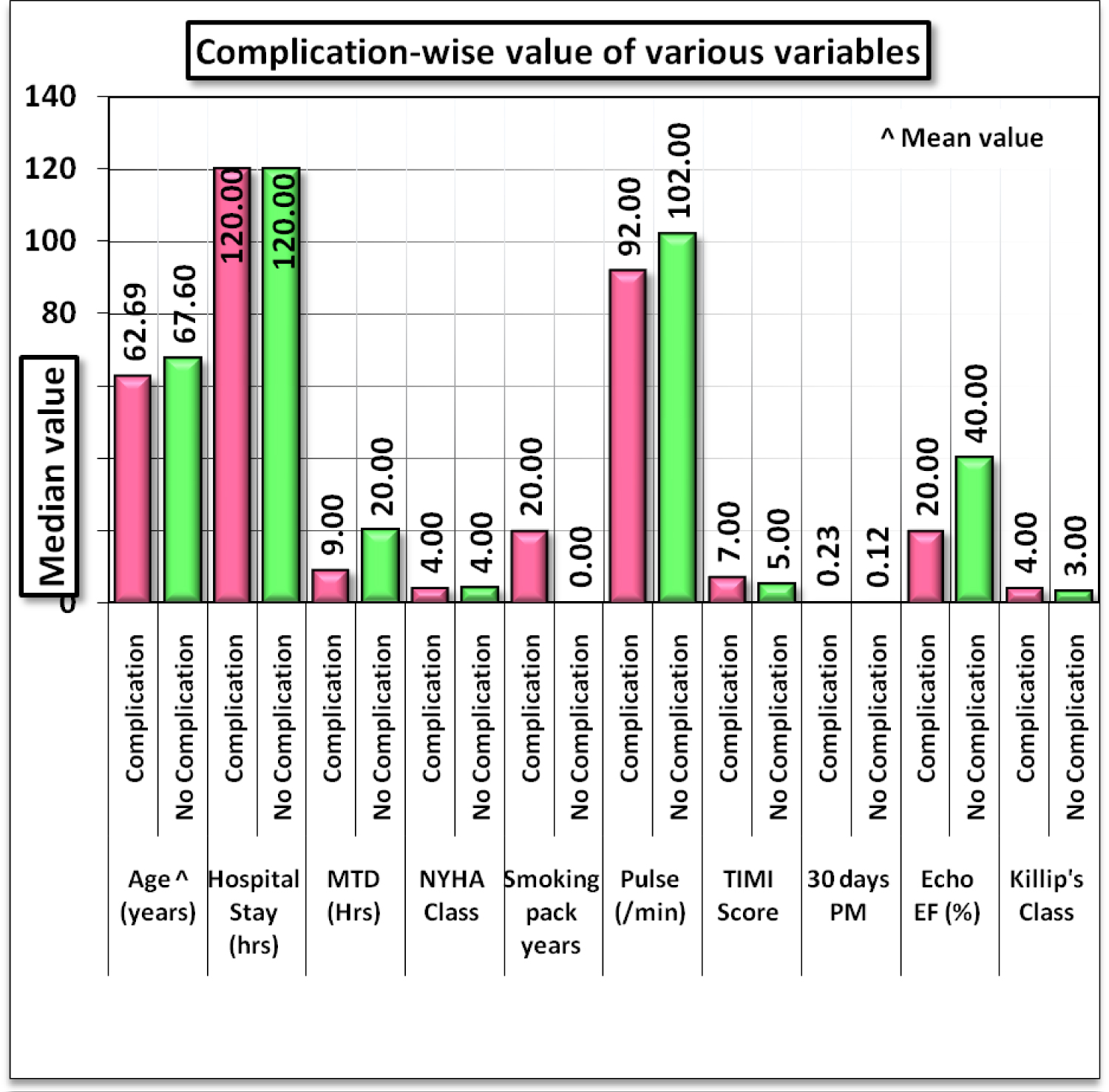

Almost 22 patients out of total 50 (44%) had Tachycardia on presentation while 21 (42%) cases had normal pulse. Respiratory examination revealed Bilateral Crepitation in 80% (40) cases. Cardiac examination reported 21 (42%) patients with elevated JVP while muffled heart sound was heard in 6 cases (12%). Mean time to access health care services, Killip class II, EF ≤ 20% are detrimental factors in complications of ACS patients as noted in Table 1 which presents comparison profile of patients with and without complications of ACS.

Table 1: Comparison of patients with and without complications of ACS. View Table 1

Eleven patients out of fifty patients had inpatient stay less than 24 hours (22%) and most of patients 66% had inpatient stay more than 4 days (32/50). Referring to ECG wall changes, Anterior (40%) and inferior wall (26%) changes were most common followed by Anterolateral (14%) and infero-posterior (8%) wall changes. In present study, majority of patients i.e. 72% had cardiogenic shock, 38% ventricular tachycardia, 14% left ventricular failure, and 10% in heart blocks. Figure 1 has shown complication wise values of various variables.

Figure 1: Complication wise value of various variables.

View Figure 1

Figure 1: Complication wise value of various variables.

View Figure 1

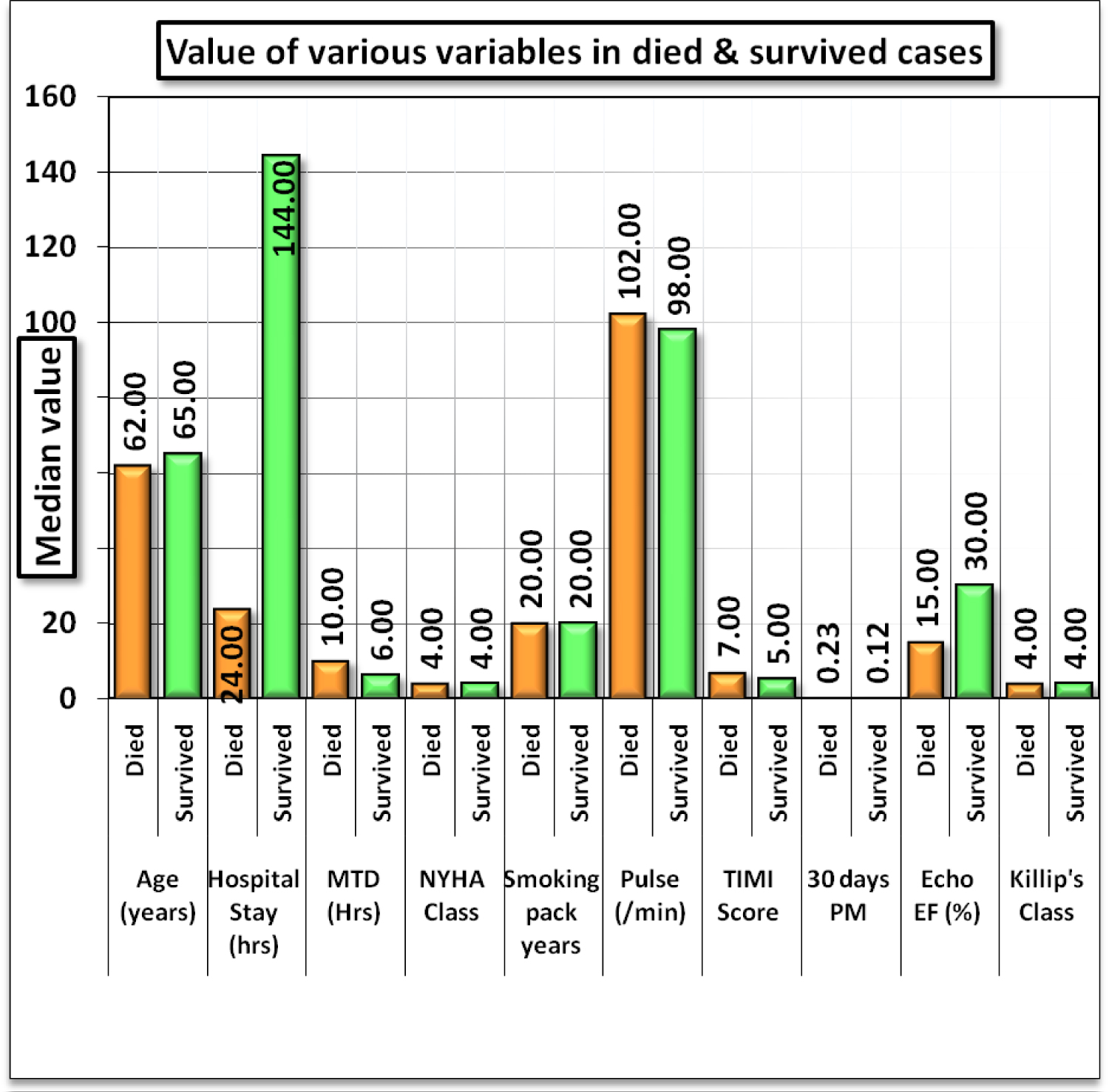

Interestingly, 24% of patients had both cardiogenic shock and ventricular tachycardia. Thrombolysis with streptokinase was treated in 46 (92%) cases. Complications occurred in 58% of patients who are not successfully thrombolysed Treatment success in terms of ECG improvement criteria was observed in 19 cases (41%) while clinical improvement in 18 cases (40%). Almost all cases received LMWH. Inotrope was given in 36 cases (72%). Mainly 66% of cases were kept on mechanical ventilation; out of that 21 on intermittent positive-pressure ventilation (IPPV) and 12 on BIPAP (Bi-level Positive Airway Pressure). More than 50% of patients were admitted in hospital more than 5 days. Out of this court of 50 people with complication, 21 (42%) people died. Figure 2 has shown comparison of value of various variables in died and survived cases.

Figure 2: Comparison of value of various variables in died and survived cases.

View Figure 2

Figure 2: Comparison of value of various variables in died and survived cases.

View Figure 2

More than half deaths were contributed by cardiogenic shock and arrhythmias remaining left ventricular failure and complete heart failure. Half of the complications (25) occurred in patients with ejection fraction ≤ 20, while EF 20-40% reported in 22 people out of 50. Cohort of 21 deaths, 14 (66%) had ejection fraction ≤ 20% while 7 (44%) had EF > 20%. Suggested in Table 2, time to acess health services, hospital stay and TTE predicting Ejection fraction are significant factor in prognostification of survival of patients.

Table 2: Comparison of various variables between cases died & survived cases. View Table 2

This study is single centre prospective Cohort study conducted in tertiary care hospital of India. Medical college chosen as research site considering patient flow, possible available facility required for basic, advanced cardiac care and being tertiary health care access facility catering all strata of population. Considering subsidy for available medical facility, study population turned to be representative of population of India. It actually gave snapshot of ACS cases presenting with complications. There is linear increase in incidence of complications of MI with increasing age; sharp rise after the age of 60 years. This study also adds evidence of being protected as female for cardiac complications [1,2]. In present study clinical profile of 50 patients with ST elevation MI presenting with complications has been studied. High incidence of patients having myocardial infarction, i.e. 58% was noted in age group of > 60 years. These observations were similar to many other studies carried out in different decades conducted in Indian population [1]. With age increased complications and deaths. In present study mean age is 63.2 years which reflects limited physical activity. Acute Myocardial Infarction is the most common cardiovascular emergency seen in medical emergency ward and it has become the leading cause of death accounting for 50% of death due to cardiovascular disease in India [12]. TTE predicting EF actually played major role in prognostification of MI related complications; interstingly patients with EF ≥ 40% offered protection against complication and mortality [2,11,14-16] EF > 40% Offers protection in complication of ACS cohort and EF ≤ 20% carries higher risk for deaths.

This cohort presented to hospital in 9 hours compared to Van den Berg, et al. [17,18] study which quotes duration of 3.5 hours. In our study 82% of patients presented before 12 hours of onset of symptoms which reflects increase in awareness of patients.

Table 3, shows that chest pain remains the hallmark symptoms in all the studies of AMI. This is followed by breathlessness (28%) and nausea/vomiting (24%) as seen in Gupta, et al. study [19,20]. Incidence of nausea and vomiting is reported by Ghanshyam, et al. [14] and Solanki [21] which matches with current study.

Table 3: Comparison of incidence of symptomatology in different studies. View Table 3

Current study (Table 4) shows hypertension remains the most important risk factor in female patient, although incidence varies from 68% to 27% in different studies except the study of David, et al. [15] and William BR, et al. [16] where it's less common than smoking and hypercholesterolemia [2,20,23]. Obesity is also an important risk factor accounting for 24% in this study; reflecting less burden compared to other studies [2,4,24,25]. This also reflects dietary habits and sedentary lifestyle of patients. Diabetes mellitus accounts for 32% in current study, close to Dantas RA study [22] while most of studies have shown less proportion [22]. In present study as well as in all other studies incidence of complications of anterior wall MI was highest followed by inferior wall MI [2,6,8,9,12]. Highest Incidence of complications in anterior wall MI reported almost half of court which was quite similar to other studies [2,4,26].

Table 4: Comparison of prevalence of risk factors in different studies. View Table 4

Cardiac failure, cardiac arrhythmia and cardiogenic shock are commonly observed complications in different studies [1,2,4,8,24,25]. Cardiac arrhythmias reported 30.4% in study conducted by Lal, et al., while 38% in present study. Cardiogenic shock was the most common complication in present study (72%) while it was lowish 30% in previous studies. Incidence of cardiac failure is also decreased in our study (14%) comparable to 13% of Lal, et al. study. Heart block accounts for 10% in present study; quite close to different studies 11% [3,7,16,18,26,27]. Incidence of mortality in present study was higher (42%), comparable to other studies conducted by Gupta, et al. (15%) [19] and 15.6% by Lal, et al. study [28]. Amongst all the complications both cardiogenic shock and arrhythmias has equal chances of causing mortality, and risk doubles when both occurred simultaneously in a same patient.

This is unique study conducted in one of developing countries addressing burden of complication of acute coronary syndrome and their outcome. This sample population is representative of population as this government tertiary hospital.

This study has addressed only one specific state of India so dietary pattern being unique was not taken into calculation. This study was conducted over short duration considering thesis deadline. Another limitation is the small number of patients, this study was conducted as part of master's dissertation over limited period.

Hypertension carries the major risk factor in deciding the complications and strict control of blood pressure should be achieved through proper treatment as per according to ACC/AHA 2017 guidelines. This study recommends to control hypertension and related other comorbdidites from Chronic diseases. It is necessary to give proper education to the public about the symptoms of myocardial infarction through proper channels, alongwith need to acess hospitals earlier. This study recommends need of strenghthening public health care system with basic investiagations so that the complications can be reduced.

Gender- male, increasing age, hypertension and other comorbidities, failure of thrombolysis treatment, ejection fraction < 40% being prevalent risk factors in ACS and prognosticification of ACS related complication, need to revise policy accordingly. Study advocates echocardiographic evaluation for prognosticificaion along with proper treatment of other comorbidities. This study also recommends proper education to the public about the symptoms of ACS through proper channels alongwith alarmin symptoms to early acess to hospital alongwith need of strenghthening public health care system, protocol with basic investiagations for reduction of complications.

Stratgey for ACS prevention shall include health education adressing lifestyle modifications, physical activity forums and platforms, Smoking ceastion clinic, regular chronic diseases control and mangement programme; improvised acess to health care, related subsidy at governments clinic; and regular annual health screening activities. Stratgey shall also adress proper treatment and follow up of all chronic diseases mangments such as diabets, hypertension and obesity mangment clinics. Government should take appropriate actions for infastructure strengthening through facility innovation, making avilability of 2 Decho and related investigation, alongwith subsidy for consultaion, investigation and treatment.

Male, elderly population, Hypertension and other comorbidities, prolonged MTD, failure of thrombolysis treatment, ejection fraction < 40% are the most important risk factors for prediction of ACS and helps in prognstification of related complications. This study recommends holistic health education of the public about the presenting symptoms through proper channels, mangment of comorbdities, early acess to health care and strenghthening public health care with basic investiagations, the complications can be reduced.

None declared.

The authors have declared no competing interest.

No funding was received at any stage of conducting this review or preparing this manuscript.