Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome is a rare disease with an incidence rate of about one in one million per year worldwide. It is caused by granulomatous, nonspecific inflammation of the cavernous sinus, which results in severe headaches, eye pain, and ophthalmoplegia. This is the case of a previously healthy 10-year-old male with a family history significant for Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma and Squamous cell carcinoma who presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with an intense recurring headache and ophthalmoplegia in his left eye. Imaging studies obtained in the form of a computer tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head, chest and abdomen showed a right paratracheal mass in addition to an enhancing lesion in the left middle cranial fossa, left cavernous sinus & left orbital apex. The patient underwent a tissue biopsy of the chest mass via video assisted thoracoscopic surgery but pathology failed to show a clear diagnosis showing only the presence of fibrosis and non-specific inflammation. Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome was suspected as a diagnosis of exclusion and corticosteroid therapy was initiated and found to be effective with resolution of his symptoms. We present this case for the rarity of Tolosa-Hunt syndrome in combination with a chest mass.

Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome, Pediatric, Cavernous sinus, Chest mass

Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome (THS) is a rare disease that is caused from non-specific, unilateral inflammation near the cavernous sinus and is typically idiopathic in nature, although there are a few events that may increase the likelihood of occurrence, such as traumatic injury, tumors, and aneurysms [1]. According to the International Classification of Headache Disorders, Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome is to be diagnosed once the following criteria are fulfilled: Unilateral headache, granulomatous inflammation of the cavernous sinus, superior orbital fissure or orbit, which is to be demonstrated by Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or biopsy, and paresis of one or more of the ipsilateral third, fourth, and/or fifth cranial nerves. Evidence of causation demonstrated by a headache also must have preceded paresis of the third, fourth, and/or sixth nerves by less than 2 weeks, or developed with it, along with the headache localizing around the ipsilateral brow and eye [1,2]. Since a headache and paresis can be indicative of other, more common diseases, it is especially critical to rule out all other possible diagnoses that may present with similar symptoms which include, but are not limited to anisocoria, diabetic neuropathy, Lyme disease, meningioma, venous thrombosis, skull tumors, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, and Lymphoma [3,4].

An MRI of the orbit is currently the most recommended test to both rule out potential neurological diagnoses and rule in THS [5-7]. In the situation where a biopsy of the cavernous sinus is needed, this is usually accomplished through a frontotemporal craniotomy followed by removal of the sphenoid bone ridge and the temporal bone base, exposing the dura propria, which is then removed to expose the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus [8]. Furthermore, additional imaging studies may be needed to rule out any associated masses in other regions of the body, as there have been reported cases where a peripheral mass caused THS-like symptoms but whose diagnosis was different [9-12]. If a mass is detected, it should be biopsied to assess for malignancy [9-12].

This is the case of a 10-year-old male who was seen at a pediatrics clinic with a primary complaint of left eye pain and swelling. According to the patient's mother, he has had a previous episode of left eye pain five months prior to presentation that spontaneously resolved, but experienced another episode of left eye pain along with eye drooping. In addition, the patient experienced vision changes, headache, and left-sided facial pain. The patient had no previous medical or surgical history and his family history was significant for squamous cell carcinoma in his maternal aunt, breast cancer in his maternal grandmother, Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma in his maternal cousin, and pseudotumor cerebri in his paternal aunt. A comprehensive physical exam revealed a 3rd cranial nerve palsy, ptosis, and decreased medial movement of the left eye as well as a palpable right cervical lymph node, which raised concerns for lymphoma. A complete blood count was significant for decreased hemoglobin levels (9.3 g/dL), hematocrit (28.4%), and mean corpuscular volume (71.4 fL), which was indicative of anemia. His white blood cell count was also 8.42109/L, and both his erythrocyte sedimentation rate (123 mm/hr) and C-reactive protein test (5.9 mg/dL) were elevated.

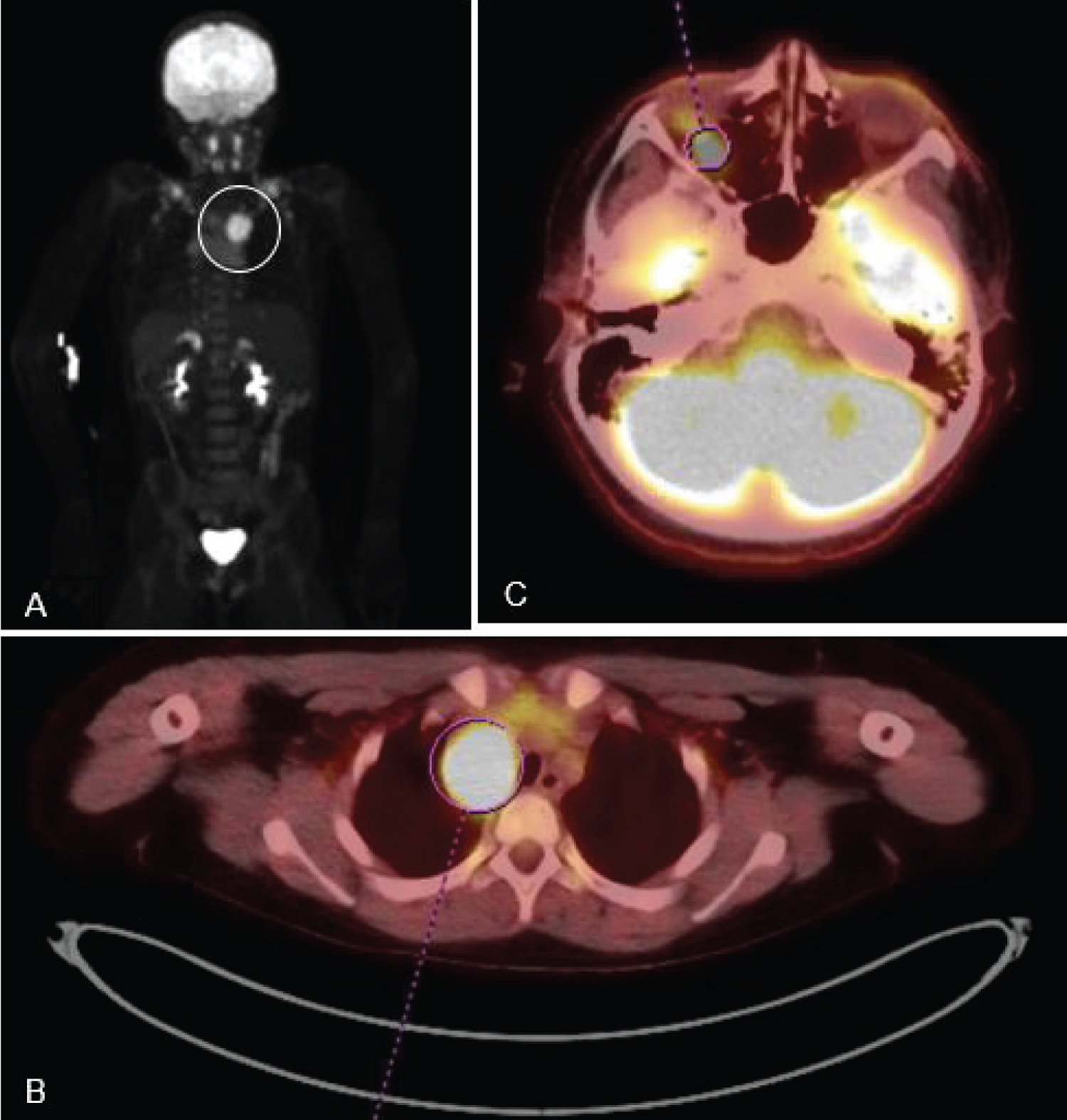

The patient was given a working diagnosis of lymphoma and was worked up further in conjunction with the Neurology, Hematology, and Oncology services via an MRI of his face, which showed an ill-defined enhancing soft tissue mass near the left orbital apex, extending to the left cavernous sinus, sphenoid wing, and foramen ovale. This was followed by a Computed Tomography (CT) of the head, neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis. Head CT showed an enhancing lesion in the left middle cranial fossa, left cavernous sinus, and left orbital apex -- the same mass that was identified on the MRI. Chest CT revealed a right paratracheal, hypo-enhancing, and non-calcified soft tissue mass measuring 4.1 × 3.4 cm that was causing a mild mass effect on the trachea and thymus. The abdominal, and pelvic CT were unremarkable. A Positron Emission Tomography scan (PET) with Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) was also performed (Figure 1A), and it was significant for hypermetabolic activity in the right paratracheal mass (Figure 1B) and as well as the left orbital apex (Figure 1C). A core needle biopsy of the paratracheal mass was performed, but the results showed tiny fragmented lymphoid cores of mixed T- and B-cells, dense fibrosis, and no definite malignancy/neoplasm, and thus were considered inconclusive.

Figure 1: (A) Full-body PET scan, showing abdominal activity in the chest (circled white); B) PET scan of chest, showing increased activity in the right paratracheal region (circled red); (C) Cranial PET scan, showing increased activity in the left orbital apex (circled red).

View Figure 1

Figure 1: (A) Full-body PET scan, showing abdominal activity in the chest (circled white); B) PET scan of chest, showing increased activity in the right paratracheal region (circled red); (C) Cranial PET scan, showing increased activity in the left orbital apex (circled red).

View Figure 1

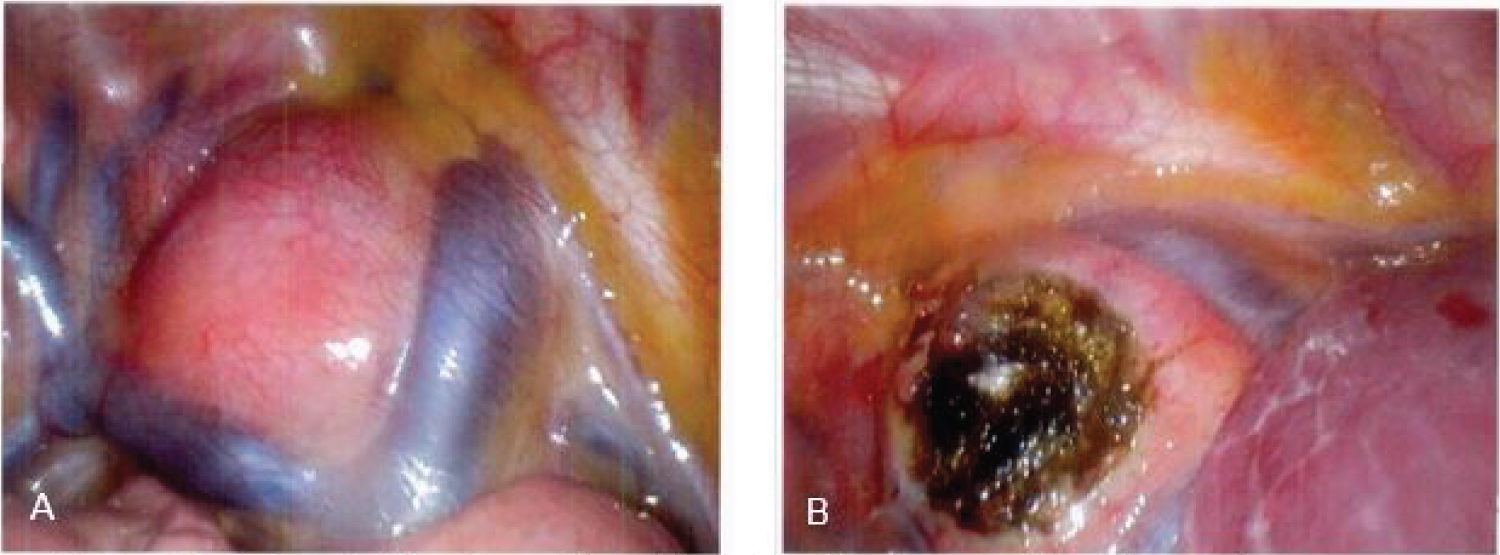

Given the ongoing working diagnosis of lymphoma, a tissue biopsy was requested and thus the Pediatric Surgery service was consulted. A biopsy of the cavernous sinus lesion was also considered, but ultimately rejected due to the high risk of performing a frontotemporal craniotomy on a child. The patient was taken to the operating room (OR) for a video assisted thoracoscopic biopsy of the right paratracheal mass. Intraoperatively, the mass was found to be located in the posterior mediastinum adjacent to the azygos vein and the superior vena cava. A large sample of the mass was excised and sent to pathology for analysis (Figure 2A and Figure 2B).

Figure 2: (A) Paratracheal mass lies adjacent to the azygos vein and superior vena cava; (B) Paratracheal mass after biopsy.

View Figure 2

Figure 2: (A) Paratracheal mass lies adjacent to the azygos vein and superior vena cava; (B) Paratracheal mass after biopsy.

View Figure 2

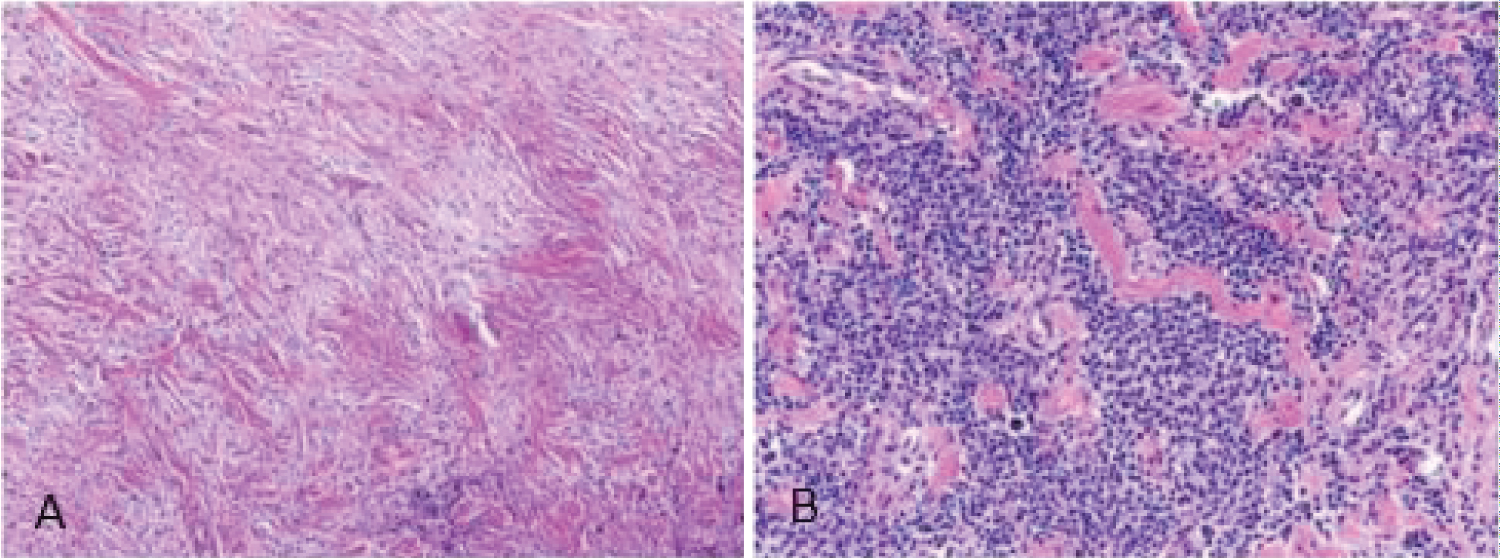

The pathology report identified the presence of fibrosis and non-specific inflammation, but did not show any signs of malignancy and was unable to give a clear diagnosis of the mass (Figure 3A and Figure 3B). A lymphoma profile of the sample was also negative for MUM1, BCL2 and 6, CD3, 4, 5, 8, 15, 19, 20, 30, 43, 45, and 79a, denying the presence of abnormal T and B lymphocytes.

Figure 3: Histology of the biopsied sample from the chest mass. (A) Sample consists of fibrous tissue, including dense, keloidal-like collagen and delicate, pale collagen. (B) Sample contained variably dense lymphocyte infiltrates consisting of mixed B- and T-cell lineage, without cytologic atypia.

View Figure 3

Figure 3: Histology of the biopsied sample from the chest mass. (A) Sample consists of fibrous tissue, including dense, keloidal-like collagen and delicate, pale collagen. (B) Sample contained variably dense lymphocyte infiltrates consisting of mixed B- and T-cell lineage, without cytologic atypia.

View Figure 3

THS is a rare disease with an incidence rate of about one case per million persons per year worldwide [2,3]. Because the illness is primarily a diagnosis of exclusion, a patient that exhibits THS-like symptoms must be thoroughly worked up to exclude as many potential diagnoses as possible.

Tsutsumi, et al. [12] reported a similar case of a male patient who exhibited symptoms of THS and had a chest mass. In this case the patient underwent similar imaging studies to our patient but in addition had a biopsy of the cavernous sinus lesionvia an orbito-fronto-temporal craniotomy. The pathology report showed highly mitotic cells along with positivec-kit, AE1/3, cytokeratin, and CD56 staining. The PET scan also showed an anterior mediastinal mass rather than a paratracheal mass, and the patient was ultimately diagnosed with metastatic carcinoma with thymic origins [12].

There have also been published case studies by Baig, et al. [10] and Pina, et al. [11] in which patients exhibited THS-like symptoms but also had associated peripheral masses in the abdomen. These masses were imaged, biopsied, and thoroughly tested, and the tissue samples stained positive for CD10, 20, BCL5, and Ki67, the markers being diagnostic for malignant Burkitt's lymphoma [10,11].

Abalo-Lojo, et al. [9] also reported a case of a male patient who initially presented with symptoms of THS and was found to have a unilateral mass in his cavernous sinus upon imaging. However, unlike our patient, corticosteroids did not help resolve symptoms and a full body CT imaging study and colonoscopy identified a mass in the cecum. A biopsy of the mass revealed a B-cell lymphoma which stained positive for CD45 and CD20; the patient was ultimately diagnosed with metastatic B-cell Lymphoma [9].

The recommended treatment plan for children with Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome is a three- to four-month tapered prescription of corticosteroids starting at approximately one mg per kg of body weight per day [13]. Follow-up appointments every three or six months are also recommended to reassess treatment effectiveness and disease progression; most patients with THS show improvements at about three months post-discharge, but complete recovery may not occur until at least two years later [13-15].

Because of these findings, the patient was given an exclusionary diagnosis of THS and was initiated on a course of corticosteroid therapy (30 mg Prednisone daily). The patient reported an improvement of symptoms after completion of the in-hospital therapy and was discharged home with an additional 30-day prescription of Prednisone. At the follow up appointment at three months postoperatively, the patient was asymptomatic, but the repeat imaging studies showed no changes to the paratracheal and cavernous sinus lesions. Currently the patient is being closely monitored with plans of repeat imaging studies at six months post-operatively with consideration for chest mass excision if still present. This is a unique presentation due to the rarity of Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome with the added presence of a mediastinal mass. This case further highlights THS as a diagnosis of exclusion, as other, more common differential diagnoses such as lymphoma may present with similar findings and thus must be ruled out first.

The authors of this report would like to extend a special thank you to Dr. Craig Zuppan from the Pathology Department for his assistance with the histopathological analysis of the samples.

None.

The following authors have no financial disclosures: WI, MS, LG, AR.

All authors listed contributed equally to this manuscript.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.