Endometriosis has a major impact on women's sexual health, lessening fertility and causing pain and reduced sexual desire in at least 50% of patients. This article investigates the relationship between infertility and sexual intercourse concerns and illness intrusiveness. Since both pain and illness can be interjected as malevolent internal objects, we also looked at the mediating effect of pain representation as a malevolent object on those relationships. Out of 116 women, 58 met our inclusion criteria (M = 37.37 years, SD = 5.10). We used the Endometriosis Health Profile-30, the Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale, and the Pain Personification Questionnaire. Results demonstrated that pain representation as a malevolent object totally mediated the relationship between both infertility and illness intrusiveness as well as sexual intercourse concerns and illness intrusiveness. Results highlight the importance of a psychodynamic approach to endometriosis, allowing for the effect of vulnerabilities developed in early childhood to be considered while approaching this illness.

Endometriosis, Illness Intrusiveness, Sexuality, Intercourse, Infertility, Pain malevolence

Endometriosis is a chronic gynecological condition affecting around 10% of fertile women. Key symptoms are dysmenorrheal, dyspareunia, dysuria, dysphasia, infertility, and chronic pelvic pain [1,2], without any direct relationship between illness severity and pain intensity [3,4].

The diagnosis takes between 8 and 11 years [5,6] and is often only made together with that of infertility (the inability to get pregnant despite having frequent, unprotected sex for at least a year): 25 to 50% of infertile women have endometriosis, and 30 to 50% of women with endometriosis are infertile [7,8].

Studies on psychological distress in endometriosis are scarce, and those that do exist focus mainly on identifying depression, anxiety, and lessened quality of life [9-12]. Research into sexual function in endometriosis has been increasing [5,13-15], mainly looking at infertility, which is significantly related to depression and anxiety [16-18], and dyspareunia, which is present in around 50% of patients. Dyspareunia deeply impacts sexuality, as the pain is felt both physically and psychologically: Significant negative effects on desire, excitement, sexual activity, and orgasm [19-21] can take place, with obviously predictable challenges for couples [22-26].

Illness intrusiveness has been studied extensively regarding many chronic illnesses, such as cancer, rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis [27,28] and is defined as the feeling by patients that their illness or associated treatments interfere with daily activities. Having no direct relationship with illness severity or pain intensity, illness intrusiveness is positively correlated with depressive and anxious symptomatology and lessened quality of life [29-31]. Despite the lack of data, illness intrusiveness seems likely to be present in endometriosis, given the impact of the disease on issues central to illness intrusiveness, such as work, interpersonal relationships, and sexuality [32-35].

Pain is a principal characteristic of endometriosis, affecting up to 80% of patients [35,36]. However, its role on psychological suffering is still not clear [3,37]. Using object relations theory, Schattner, et al. [38] demonstrated that women with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, a chronic illness with similarities to endometriosis (undetermined etiology, immune system dysfunction, widespread impact on the body), tend to construe their illness as an internal object capable of influencing both their affective states and behaviors; the same seems to happen associated to pain. These representations, when negative or malevolent, correlate with higher levels of depression and illness intrusiveness [39,40]. The new relationships established throughout life tend to be influenced by representations established during early interactions [41-43]. Hence, it might be argued that the attribution of malevolence to the interjected pain might stem from early experiences with objects felt as neglecting or abusive [44-47], and that this might influence the degree to which the disease is experienced as intrusive.

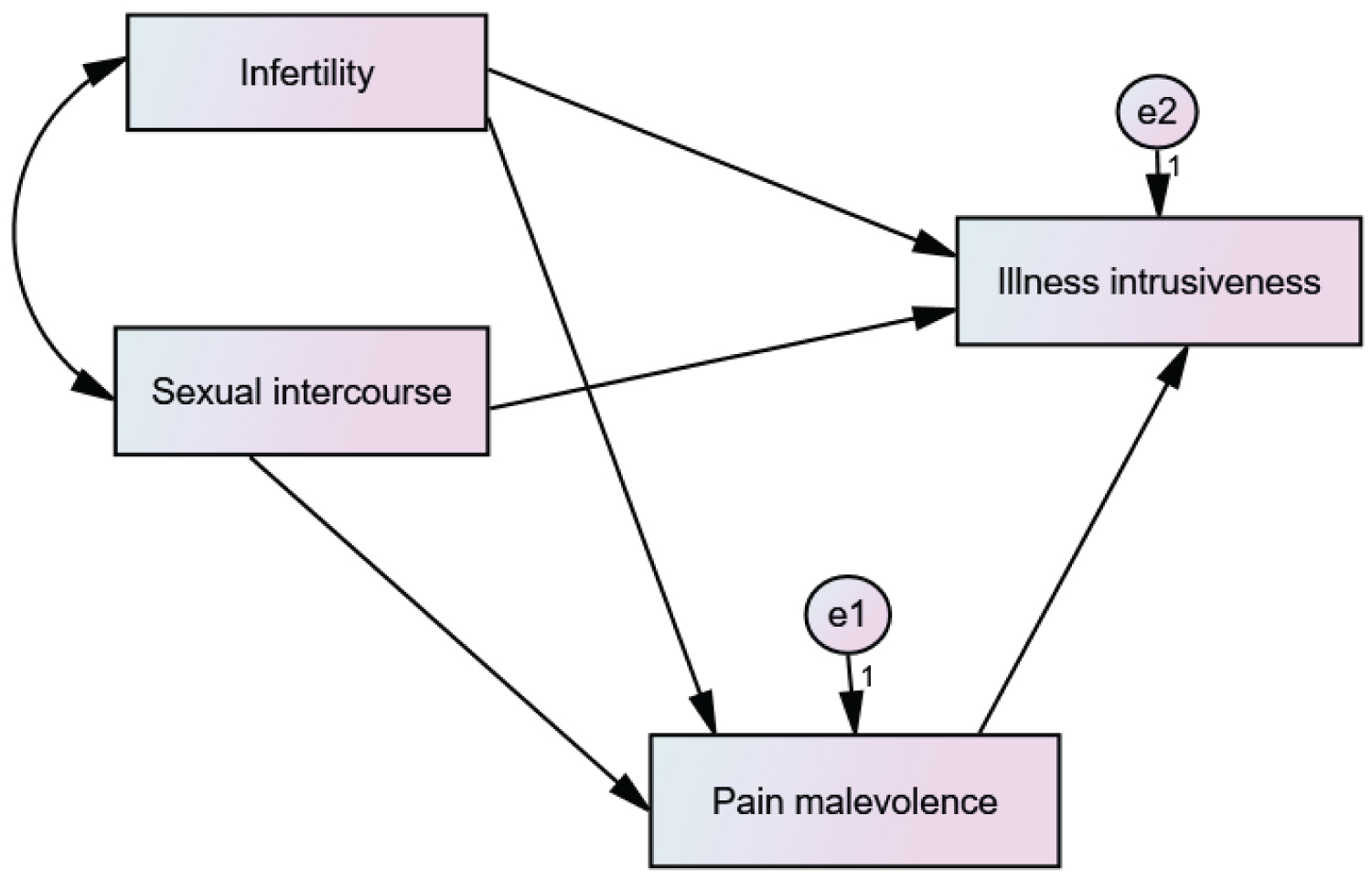

Given the tendency for endometriosis to be seen as intrusive and deleterious, we hypothesized that both infertility and sexual intercourse concerns (including dyspareunia and reduced arousal) might be related to illness intrusiveness. We also predicted that pain malevolence would mediate the relationship between these two dimensions and illness intrusiveness. Given the continuity between pain and illness representation [39], we also hypothesized that reduced fertility, even if unaccompanied by physical pain, would be experienced in a similar fashion. We expected these relationships to be significant even when controlling for important co-variables.

A sample of 116 Portuguese women participated in a larger study of endometriosis and psychological distress, with only 58 women meeting the criteria for this investigation. Given our focus on infertility and sexual intercourse disturbances, only women reporting such issues participated. The exclusion criteria were: Age above 51 (average age women enter menopause) [48], a psychiatric hospital admission within the previous year, not speaking native Portuguese, and having less than a 6th grade education. Following an online call for volunteers, data was collected anonymously both online, using a Google form, and in-person, both at small gatherings organized specifically for this intent with the Portuguese Support Association for Women with Endometriosis and at the Specialized Center for Endometriosis at the Hospital Lusíadas, Lisbon after receiving the hospital's health ethics authorization.

Participants ranged from 22 to 51 years of age (M = 37.37, SD = 5.10) and 72.5% had at least a bachelor's degree. Most were in a romantic relationship (96.6%) and had no children (55.2%). The average number of years with pain was 17.41 years (SD = 10.22) and time since diagnosis averaged 5.41 years (SD = 4.70). Other gynecological illnesses were present in 6.9% of our sample, and 24.1% had previously received a psychiatric diagnosis.

Participants filled out a survey requesting socio-demographic and clinical information: Age, education level, relationship status, parity, number of years with pain, number of years since diagnosis, other gynecological illness, and previous psychiatric diagnoses.

The Endometriosis Health Profile-30 [49,50] is a 53-item instrument measuring the condition's impact on women's lives. The core instrument comprises five scales: Pain, control and powerlessness, emotional well-being, social support, and self-image. Six supplementary modules include work, relationship with children, sexual intercourse, relationship with doctors, treatment, and infertility. All scales showed high internal reliability (Cronbach's α between 0.83 to 0.93 on core questionnaire and 0.79 to 0.96 on modules) for the Portuguese version. This study focused on the Sexual Intercourse and Infertility modules, assessing the presence of pain and inhibited sexual arousal and reduced fertility, respectively, and also the degree to which these issues were felt to be worrisome. Cronbach's alphas for the current sample were 0.93 and 0.92, respectively.

The Illness Intrusiveness Ratings Scale [28] consists of 13 items assessing the extent to which disease-and treatment-related factors interfere with meaningful life concerns, such as family relations, sexuality, or work. It generates a total score and three sub scores: Relationships and personal development, intimacy, and instrumental. The original version has high levels of reliability (Cronbach's α ranging from 0.78 to 0.97). We obtained the author's permission and followed Van de Vijver & Hambleton's directives for translating [51] the tool into Portuguese. We used the total scale score, and Cronbach's α was 0.92 in the present sample.

The Pain Personification Questionnaire [39] is an 11-item self-report measure investigating whether participants experienced pain as a malevolent entity residing within themselves. The original instrument generates a total score with good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.77). We requested the authors' permission and followed Van de Vijver & Hambleton's directives [51] for translating the tool into Portuguese. Our Cronbach's α was 0.86.

A preliminary analysis (Table 1) looked at the relationship among our target variables and between them and the socio-demographic and clinical ones (age, education level, relationship status, parity, number of years with pain, number of years since diagnosis, other gynecological illness, and previous psychiatric diagnoses). No significant correlations were found, thus no co-variables were introduced into the models. AMOS 21 software then tested for any meditational effect of pain malevolence on the relationship between illness intrusiveness and infertility and sexual intercourse concerns. We tested a direct model of infertility and sexual intercourse concerns on illness intrusiveness and then a meditational one (Figure 1). Infertility and sexual intercourse concerns were entered as independent variables, while pain malevolence served as the mediator, and illness intrusivenesswas the dependent variable. Bootstrapping (with 1,000 samples to build 95% confidence intervals) assessed significance levels and calculated indirect effects.

Figure 1: Direct and indirect associations between illness intrusiveness and infertility and sexual intercourse concerns, with pain malevolence as a mediational variable.

View Figure 1

Figure 1: Direct and indirect associations between illness intrusiveness and infertility and sexual intercourse concerns, with pain malevolence as a mediational variable.

View Figure 1

Table 1: Correlations between study variables. View Table 1

Regarding the direct model, infertility (β = 0.26, SE = 0.125, p < 0.05; 95% CI [0.009, 0.491]) and sexual intercourse concerns (β = 0.36, SE = 0.124, 95%, p < 0.05; 95% CI [0.105, 0.586]) were both found to relate to illness intrusiveness. The model explained 23% of this variance. Regarding the meditational model, infertility (β = 0.32, SE = 0.149, p < 0.05; 95% CI [0.019, 0.608]) and sexual intercourse concerns (β = 0.39, SE = 0.144, 95%, p < 0.05; 95% CI [0.067, 0.5640) were both related to pain malevolence, while this meditational variable tended to relate to illness intrusiveness (β = 0.30, SE = 0.162, 95%, p < 0.10; 95% CI [-0.003, 0.628]). No significant direct effects of infertility or sexual intercourse concerns were found on illness intrusiveness. However, significant indirect effects through pain malevolence were revealed for both infertility (β = 0.10, SE = 0.087, 95%, p < 0.05; 95% CI [0.000, 0.335]) and sexual intercourse concerns (β = 0.12, SE = 0.077, 95%, p < 0.05; 95% CI [0.008, 0331]). This reveals that pain malevolence totally mediated the relationship between infertility and sexual intercourse concerns and illness intrusiveness, explaining 30% of its variance.

As hypothesized, our results showed that both infertility and sexual intercourse concerns are significantly related to illness intrusiveness. We also demonstrated that pain representation as a malevolent object has a total mediating effect on these relationships.

Both infertility and sexual intercourse concerns seem to be important to most women throughout their fertile years [17], which emphasizes how potentially troublesome these concerns are for endometriosis sufferers. When looking at the mediating effect of pain malevolence, we confirmed that the lack of physical pain in infertility is not necessarily important. Given the theoretical continuity between pain and illness malevolence due to chronic illness [38], infertility may be perceived as similarly malevolent.

These results draw attention to the importance of early relationships on patients' emotional development. Representations developed in childhood tend to persist throughout life and are assumed to serve as a model for new ones [42-44], including those developed in adulthood resulting from chronic illness. The attribution of malevolence to both pain and illness seems to reflect an inherent difficulty of some women to mobilize internal resources to manage the illness's impact. In fact, these women perceive the disease to be deeply intrusive and malignant. The attribution of malevolence to chronic illness pain might, therefore, result from early experiences with objects felt to be unavailable, rejecting, or neglecting [45-47].

We suggest that a psychodynamic approach could be used when addressing the psychological impact of endometriosis. This might deepen understanding of women's difficulties in light of their relational experiences, facilitating work on any vulnerabilities that potentially hinder their adaptation to this unsettling chronic illness.

The small sample size is a limitation of note in this study. Larger samples would enable future researchers to corroborate these findings. Dyspareunia pain intensity should be controlled for, as well, when exploring its impact on women's well-being.

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

The findings reported in this manuscript have not been previously published and are not being simultaneously submitted elsewhere.

Original research procedures were consistent with the principles of research ethics, published by the American Psychological Association.

Funding received for this work from FCT (Foundation for Science and Technology): UID/CED/04312/2016; UIDB/04312/2020.