Many studies have explored the association between gratitude and depression, but no meta-analysis has been reported. The purpose of this meta-analysis was to fill that gap. The meta-analysis synthesized the association in 70 reported effect sizes from 62 published and unpublished articles, involving a total of 26,427 child, adolescent, and adult participants. The studies were completed by different research teams, using different samples, different measures, and various correlational research designs. The results showed a significant association between gratitude and depression, r = -0.39 (95% confidence intervals -0.44, -0.34), indicating that individuals who experience more gratitude have lower levels of depression. The results did not vary significantly with the measure of gratitude or depression used, whether the study was longitudinal or cross-sectional, the age of participants or the percentage of female participants, suggesting a robust connection between higher levels of gratitude and lower levels of depression. The findings show a substantial association between gratitude and depression. The association provides a reason to explore further the effects of gratitude-focused interventions as a method to alleviate depression and to prevent the development of depression.

Depression, Gratitude, Meta-analysis, Prevention, Treatment

Depression is a mood disorder that often includes sadness or irritability, along with lack of interest in daily activities, together with appetite change, sleep disturbance and feelings of worthlessness and guilt [1]. Functional consequences of depression can be physical, social, and occupational, including impaired ability to concentrate and make decisions; in severe cases, individuals cannot take care of their basic needs and may be mute or catatonic [1]. Individuals experiencing depression show higher rates of unemployment, relationship breakdown, education dropout [2], and suicide [3].

Depression is a common health problem. Over 264 million people suffer from depression worldwide, and it is one of the leading causes of disability and a major contributor to the global burden of disease [4].

McCullough, et al. described gratitude as a tendency to think of or respond with appreciation for the kindness of others and the positive experiences and outcomes obtained from them [5]. A review by Wood et al. presented a new model of gratitude which incorporates the gratitude that comes from appreciating the kindness of others together with the gratitude that comes from habitual focus on the positive aspects of life [6]. This definition has become known as the life orientation approach and is a commonly used definition in current gratitude research [6].

Although gratitude is usually conceptualized as a trait, it can be cultivated and practiced. For example, Emmons and McCullough conducted longitudinal research on the association between gratitude and mental health [7]. Participants were assigned to one of three groups. The first group wrote about things they are grateful for, the second group wrote about daily hassles, and the third group wrote about a neutral topic. The findings suggested that participants who practiced gratitude by writing about things they are grateful for showed better mood, coping, and physical health than the other participants.

Studies have found that people with higher levels of gratitude report more optimism, positive affect, and satisfaction with life [5,8]. People high in gratitude also have higher self-esteem and evaluate themselves more positively [9].

Gratitude is a key construct in the positive psychology movement [10], which has gained momentum over the past two decades, with its focus on positive thoughts and behaviors. Positive psychology focuses on virtues and strengths to treat and protect against pathology [10]. These virtues include positive constructs such as optimism, hope, and gratitude.

Many studies have investigated the association between gratitude and depression. These studies are relevant to the existence of a causal connection between gratitude and depression in that an association is a foundation for a causal association. Hence, the results of association studies may provide useful information about the potential for gratitude increases, however produced, to either prevent the development of depression or to help alleviate existing depression.

The majority of the research on the association between gratitude and depression has used samples of undergraduate students. In recent years, evidence for a connection between gratitude and depression has also come from studies using a variety of sample groups. These sample groups include young people [11-13], adults and older people [2] and people who have experienced trauma, including patients with chronic illness [14,15].

There are currently two main measures of gratitude used in research. The most commonly used is the Gratitude Questionnaire-6 (GQ-6; [5]). The GQ-6 is a six-item self-report measure with two reverse-scored items. Participants are asked to rate their answers on a scale from one to seven (1 = "strongly disagree", 7 = "strongly agree"). Examples of the items include "I have so much in life to be thankful for" and "I am grateful to a wide variety of people". Although the GQ-6 is a unifactorial measure, the items capture both gratitude towards the good deeds of others and a habitual focus on the positive aspects of life [6]. Scores on the GQ-6 correlate substantially with measures of related constructs such as hope, optimism and life satisfaction [5], thus providing evidence of validity. Also, the GQ-6 has good internal reliability with Cronbach's alpha between 0.82 and 0.87 [5].

The other popular measure of gratitude is the Gratitude Resentment and Appreciation Test (GRAT; [16]). This measure is based on a multifactor model. The GRAT is a 44 item self-report measure with five reverse-scored items. Participants are asked to rate their answers on a scale from one to nine (1 = "I strongly disagree"; 9 = "I strongly agree"). There are three subscales: Appreciation for life's simple pleasures, sense of abundance, and social appreciation. An example item is "Life has been good to me".

The GRAT and the GRAT short form, with 16 items, have both been shown to have good validity and reliability [16]. A meta-analysis of the reliabilities of gratitude measures showed GRAT has good internal reliability with Cronbach's alpha 0.92 [17].

There are many measures of depression. A commonly used measure for depression is the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; [18]). The CES-D is a 20-item self-report measure used to assess the frequency of depressive symptoms in the past week. Participants rate themselves on a scale ranging from zero (rarely or none of the time) to three (most or all of the time). Example items include "I felt sad" and "My sleep was restless" [18]. Reliability, validity and factor structure are shown to be similar across different populations and different types of depressive symptoms [18]. Cronbach's alpha has been reported as 0.90 [19].

Three other measures of depression have been commonly used in studies of the relationship between gratitude and depression. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) is a 42-item self-report measure of depression, anxiety and stress developed by Lovibond and Lovibond [20]. Participants are asked to rate how much a statement applies to them over the past week on a scale ranging from zero (never) to three (almost always). An example item is "I felt that life was meaningless". Evidence shows the DASS to be a valid and reliable measure of depression in clinical and non-clinical samples [21]. Cronbach's alpha of the depression subscale of DASS has been reported as 0.96 in clinical samples [22] and 0.95 in non-clinical samples [21].

The Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd edition (BDI-II; [23]) is a 21-item self-report scale that measures the severity of depressive symptoms over the past two weeks. Each item is rated on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from zero to three. The BDI-II shows good validity and reliability; Cronbach's alpha is reported to be 0.92 in psychiatric outpatient samples and 0.93 in non-clinical samples [23].

The final measure common to the relevant studies is the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; [24]). It is a 14-item measure of anxiety and depressive symptoms. An example item is "I feel as if I am slowed down". Participants rate themselves in the past week on each item using a scale that goes from zero (not at all) to three (nearly all the time) Reliability and validity of the depression scale has been demonstrated in numerous studies with medical patients; Cronbach's alpha for the depression subscale is reported as 0.82 [24].

Although many studies have examined the relationship between gratitude and depression, no meta-analysis has been reported on the association between these two variables. The aim of this study was to use meta-analysis to combine results from studies on the association between gratitude and depression and find an overall weighted effect size. The main research hypothesis was that a higher level of gratitude would be associated with fewer symptoms of depression. We had no specific hypotheses regarding moderators of the size of the association, so we conducted exploratory moderator analyses, using meta-regression or subgroup analyses, to test as moderators: a) Mean sample age; b) Percentage of female participants; c) The gratitude measure used; d) The depression measure used, and e) Whether the study was cross-sectional or longitudinal.

This meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; [25]). We developed a protocol for this meta-analysis and registered it at Prospero [26]. A record of the registered protocol for this meta-analysis can be found at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=CRD42020193842.

We conducted a systematic literature search to locate reports of relevant studies, including published and unpublished studies. Online databases searched included PsychINFO, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. Search terms included gratitude, depress*, associat*, correlat*, and predict*. Boolean operators AND and OR were used to refine the search. We screened the results from these searches by title and abstract initially and then focused on relevant full articles.

To reduce the risk of the file drawer problem, we sent emails to corresponding authors of all included articles to request any unpublished or in press research relevant to the relationship between gratitude and depression. Also, we reviewed the reference list of each included article to identify any other studies of interest.

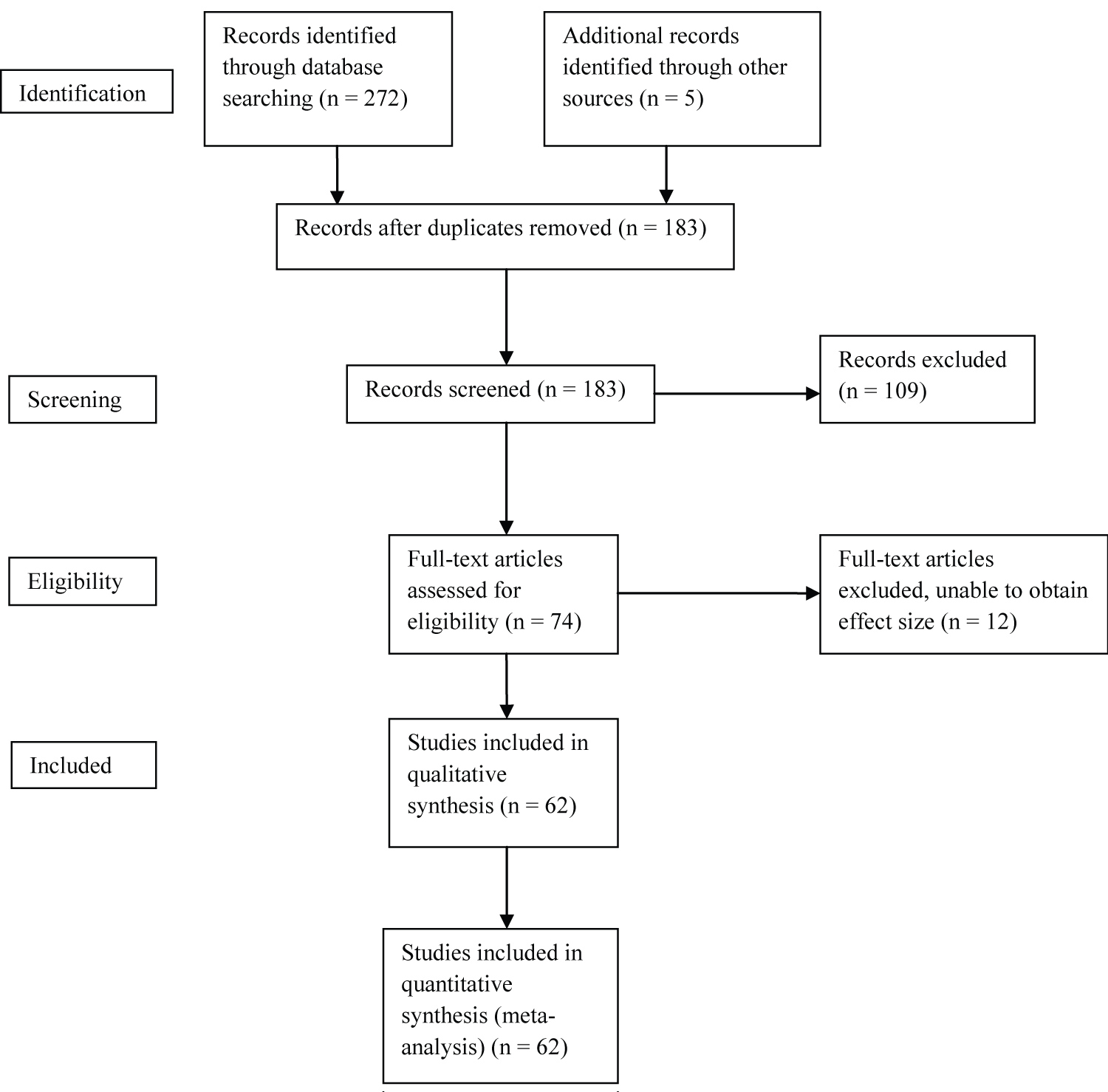

In order to be included in this meta-analysis, the report or data set had to provide the association between gratitude and depression. Studies using either cross-sectional design or longitudinal design were eligible for inclusion the titles and abstracts of identified articles were reviewed, and irrelevant articles were excluded. The full texts of remaining articles were reviewed to determine if they met the eligibility criteria. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA study flow diagram.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram showing identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion of articles.

View Figure 1

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram showing identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion of articles.

View Figure 1

The data recorded for each study included effect size or data necessary to calculate effect size, along with moderator information. Potential moderators were percentage of female participants, mean participant age, gratitude measure used, and depression measure used. Gratitude measures used were coded as GQ, GRAT or other. Depression measures used were coded as CESD, BDI, DASS-Depression, or other.

When there were multiple measures of gratitude reported in one study, to avoid biasing the results by reporting too many effect sizes from one sample, we used an average effect size. Each study was coded as either cross-sectional or longitudinal. For studies that were longitudinal the number of weeks between measuring gratitude and measuring depression was recorded. The effect size reported for longitudinal studies was chosen as the relationship between baseline gratitude and the longest follow-up of depression.

In some studies, there were missing data for moderator analysis. Corresponding authors were contacted in an attempt to gain access to the missing data. Where mean age was not provided for the study, the median was used as a substitute. Where other data were missing, the study was excluded from the related moderator analysis.

One of us entered data, another one then checked the entries, the third one of us independently checked data from 20% of articles. Using the standard of a disagreement of less than 5% is an agreement, we found an inter-rater agreement of 94%. Follow-up discussion led to all authors agreeing on the final data set.

We used r for the effect size and meta-analysis software Comprehensive Meta-Analysis by Borenstein, et al. [27]. To generalize beyond the data set, we used the random effects model, as suggested by Borenstein, et al. [28]. Under the random effects model, it is assumed that the true effect size varies from study to study. Random effects models produce larger confidence intervals compared to fixed effects models and lead to more conservative conclusions [29].

We used meta-regression to conduct exploratory analysis of continuous-data moderators. We used the Q statistic to test significance in moderator analyses. Publication bias was evaluated using observation of a funnel plot and the Duval and Tweedie [30] trim and fill procedure.

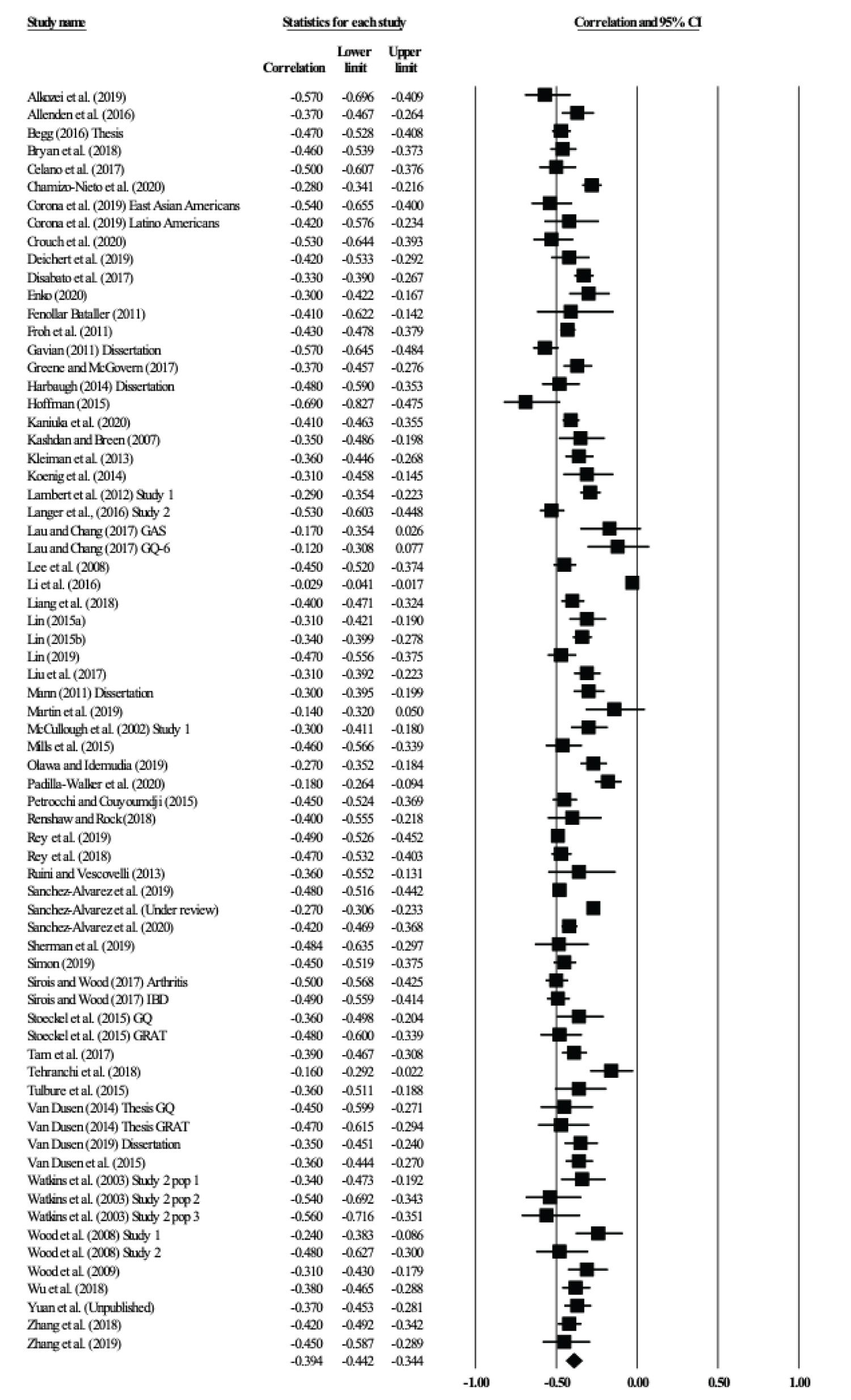

This meta-analysis synthesized 70 effect sizes from 62 published and unpublished studies, with a total of 26,427 participants. Table 1 shows the key characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis. Figure 2 shows a forest plot of correlation coefficients and confidence intervals for studies included in the meta-analysis. A fixed effects analysis of homogeneity indicated that variance between studies was significant Q (69) = 2227.81, p < 0.001 and I2 was 96.9. These results suggest the presence of heterogeneity, so we used the random-effects model for the meta-analysis. The overall weighted correlation coefficient was significant, r = -0.39, 95% confidence interval (-0.44, -0.34), p < 0.001. The data file for the meta-analysis is available at The Association between Gratitude and Depression [34].

Figure 2: Forest plot and effect size for each study.

View Figure 2

Figure 2: Forest plot and effect size for each study.

View Figure 2

Table 1: Key characteristics of the studies included in this meta-analysis. View Table 1

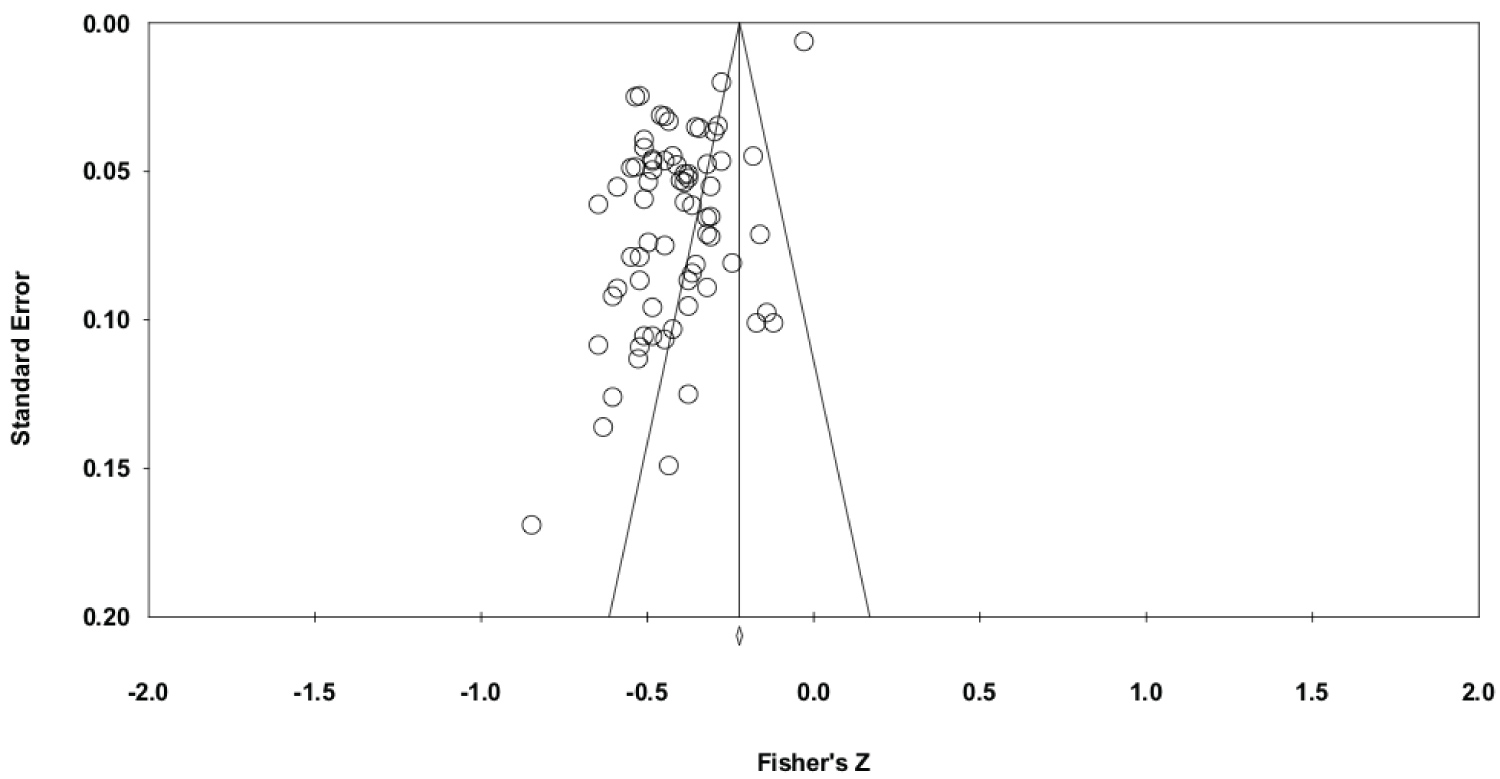

The classic fail-safe N test indicated that 3571 correlation coefficients averaging null results would need to be added to the meta-analysis to reduce the current overall correlation coefficient to a non-significant level. The funnel plot, presented in Figure 3, shows that the distribution of correlational coefficients is not symmetrical, indicating some publication bias may be present. The Duval and Tweedie trim and fill analysis suggested that 13 studies be removed from the funnel plot, leaving an adjusted effect size of r = -0.36, 95% CIs (-0.40, -0.32), down slightly from the unadjusted r of -0.39.

Figure 3: Funnel plot of standard error by Fisher's Z.

View Figure 3

Figure 3: Funnel plot of standard error by Fisher's Z.

View Figure 3

We used meta-regression to examine whether sample mean age or percentage of female participants in samples had a moderating effect on the relationship between gratitude and depression. Mean age did not have a significant moderating effect, r = 0.001 (-0.001, 0.002), p = 0.31, with study means ranging from 10-years-old to 74. Percentage of female participants did not have a significant moderating effect, r = 0.000 (-0.002, 0.002) p = 0.48. Type of gratitude measure, depression measure and whether the study was longitudinal or cross-sectional did not explain a significant proportion of between-study heterogeneity. Table 2 shows the results of these subgroup analyses.

Table 2: Moderator results. View Table 2

A meta-analysis of 70 effect sizes based on the responses of 26,427 participants found that higher gratitude was significantly associated with lower depression. The weighted average association between gratitude and depression was r = -0.39. An adjustment suggested by the Duval and Tweedie assessment for publication bias caused by Small N studies reduced the meta-analytic r slightly to -0.36. The results, which indicate a medium negative relationship between the two variables according to guidelines from Cohen [35], support the hypothesis that higher levels of gratitude would be associated with lower levels of depression.

As the Q statistic test and I squared percentage showed significant heterogeneity in effect sizes, we examined several possible moderators in the meta-analysis. There was no evidence that the degree of association varies with sample mean age or the percentage of female participants. Subgroup analysis provided no evidence to show that the specific measures used for gratitude and depression had a moderating effect on the association between the two variables. There was a marginally significant trend in the direction of cross-sectional studies showing a higher effect size than longitudinal studies. All moderator subcategories showed a significant negative association between gratitude and depression.

The current findings are consistent with the positive psychology model [10]. Individual studies have shown that positive-psychology constructs such as optimism and hope have shown similar correlations with depression [36,37].

The results from this meta-analysis are consistent with research focusing on gratitude interventions as a treatment for depression. A number of studies have examined the effects of gratitude interventions on depression; reviews and meta-analyses have found that the effects were significant but small, especially when the comparison group received an active placebo [6,38,39]. Hence, some or all of the intervention effects may be due to placebo or nonspecific aspects of the interventions, and the connection between higher gratitude and lower depression may be due to various factors. It may be that gratitude reduces depression [9], as suggested by the results of some intervention studies (e.g., Cregg & Cheavans [38]), or depression may reduce gratitude. It is also possible that a third variable, such as specific genes [40], could lead to both high gratitude and low depression. Finally, there might be reciprocal and continuous relationships between gratitude and depression such that increases in the experience of gratitude lead to alleviation of symptoms of depression, and alleviation of depression in turn allows individuals to more fully experience and be grateful for positive elements of life.

A strength of the present meta-analysis is that it quantified the extent of the association between gratitude and depression across many studies, with a large total number of participants and diverse samples and research groups. While an asymmetrical distribution of correlation coefficients in the funnel plot displayed in Figure 3 suggests the possibility of publication bias, the Duval and Tweedie trim and fill analysis suggests that an adjustment for publication bias would only have a minor impact on the overall effect size.

Another strength of the meta-analysis is that most included studies used psychometrically sound measures of gratitude and depression. The reliability and validity of the measures helps ensure that the meta-analytic results are meaningful. A final strength of the meta-analysis was that the large number of included studies provided reasonable power to search for moderators that might be associated with the effect size.

One of the limitations of this meta-analysis is that all included studies used measures of self-report for both variables. The exclusive use of self-report measures creates the possibility of inflated correlations due to same-method and same-source response bias [41].

Future research could examine whether gratitude interventions help prevent the development of depression. Also, future research could use longitudinal analyses to test for reciprocal relationships between gratitude and depression.

High heterogeneity of effect sizes in the present meta-analysis suggests that there might be moderators of effect size. However, none of the moderators examined in this meta-analysis showed significant evidence of an effect. One interesting potential moderator would be whether individuals feel grateful (the cognitive and emotional elements of gratitude) or express gratitude to others (the behavioral aspect). Any differences in association with depression might provide valuable clues about how best to structure gratitude interventions.

In conclusion, the significant association between gratitude and depression found in the present meta-analysis, together with previous research focusing on the effect gratitude interventions have on lessening depression, suggests that more research is appropriate to determine the causal relationship between gratitude and depression.

The authors have no conflicts of interest and have no financial disclosures to make related to this work.