Tuberculosis is one of the leading causes of mortality from infectious diseases in many countries. To date, there has not been a satisfactory explanation for the gender imbalance in the prevalence and mortality from tuberculosis. The gender differences in tuberculosis mortality in Russia are among the highest in the world.

The aim of this study was to test the hypothesis of a close relationship between alcohol consumption and the gender gap in tuberculosis mortality rate in Russia at the aggregate level.

The Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) time series analysis was used to estimate the relationship between population drinking and gender gap in tuberculosis mortality between 1980 and 2015.

The results of analysis also indicate that 61.3% of the gender gap in tuberculosis mortality in Russia could be attributed to harmful drinking.

The results of present study indicate that harmful drinking is the main behavioral driver explaining the cause of high gender differences in the mortality rate from tuberculosis and its dramatic variations in Russia.

Alcohol, Gender difference, Tuberculosis, Mortality, Russia, 1980-2015

Tuberculosis is one of the leading causes of mortality from infectious diseases in many countries [1]. In most countries, men affected more than women, with a ratio of male to female prevalence of 1.9 [2]. The probability of mortality from tuberculosis among men is more than two times higher than among women [3].

To date, there has not been a satisfactory explanation for the gender imbalance in the prevalence and mortality from tuberculosis. To explain this phenomenon, several hypotheses were put forward. The physiological hypothesis states that the biological differences between the sexes make males more susceptible to tuberculosis than females [4,5]. The behavioral hypothesis suggests that behavioral factors, such as smoking and alcohol consumption, play a significant role in gender bias in the prevalence and mortality from tuberculosis [6,7].

The link between alcohol and tuberculosis has been demonstrated in numerous studies that report a strong association between binge drinking and the incidence of tuberculosis, as well as worsening of the course of the disease [8]. The link between harmful use of alcohol and mortality from tuberculosis may be associated with biomedical and socio-behavioral mechanisms [9].

In addition to the role of alcohol in the onset of tuberculosis, there is also strong evidence of the negative impact of heavy drinking on the clinical course of tuberculosis. Alcohol dependent individuals show higher relapse rates, a higher likelihood of adverse clinical course (multidrug-resistance) and interruptions of treatment, which leads to a lack of overall treatment effectiveness [10]. It is also obvious, that alcohol abuse leads to social downward drift, social exclusion and marginalization, which can cause to exposure to tuberculosis infection in overcrowded places, including prisons [9].

Russia has 11 of the heaviest burdens of tuberculosis in the world and the third largest burden of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis [11]. The higher mortality rate from tuberculosis in Russia is explained by the sharp increase in multi-drug resistance, deterioration in the work of anti-tuberculosis services and an increase in binge drinking [12]. There is convincing evidence that alcohol is responsible for the high mortality rate from tuberculosis in Russia. For example, in St. Petersburg, over half of tuberculosis patients were heavy drinkers [13].

The gender differences in tuberculosis mortality in Russia are among the highest in the world [14]. The aim of this study was to test the hypothesis of a close relationship between alcohol consumption and the gender gap in tuberculosis mortality rate in Russia at the aggregate level.

Data on sex-specific tuberculosis mortality rates (per 1000.000 of the population) from 1980 to 2015 were taken from the Russian State Statistical Committee (Rosstat). The level of alcohol consumption (in litres per capita) in Russia has been estimated using the indirect method [15].

The Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) time series analysis was used to estimate the relationship between population drinking and gender gap in tuberculosis mortality between 1980 and 2015. This method is most commonly used to reduce the risk of false correlation between the time trends [16]. The first order difference of time series was used to remove time trends. A time series analysis was performed using the statistical package "Statistica 12. StatSoft".

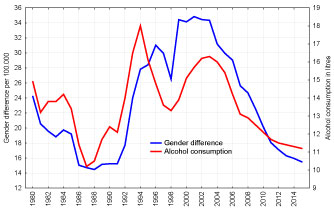

Figure 1 illustrates both the direction and magnitude of changes in population drinking and gender gap in tuberculosis mortality during the study period. As can be seen, the gender difference in tuberculosis mortality has begun to decline since 1980s. In the first half of the 1990s, the overall increase in tuberculosis mortality was accompanied by an increase in gender differences in tuberculosis mortality. In the period from 1994 to 1998, there was a decrease in the gender gap before it rose again from 1998 to 2004, and then began to shrink (Figure 1). Graphical evidence also suggests that the temporal pattern of gender gap in tuberculosis mortality is closely related to changes in per capita alcohol consumption.

Figure 1: Trends in the gender gap in tuberculosis mortality and alcohol consumption per capita in Russian between 1980 and 2015. View Figure 1

Figure 1: Trends in the gender gap in tuberculosis mortality and alcohol consumption per capita in Russian between 1980 and 2015. View Figure 1

The outcomes of time series analysis suggest a statistically significant link between population drinking and the gender gap in tuberculosis mortality rate in Russia: a 1-litre increase in alcohol consumption per capita is associated with an increase in the difference between male and female tuberculosis mortality rates by 7.0%. The results of analysis also indicate that 61.3% of the gender gap in tuberculosis mortality in Russia could be attributed to harmful drinking.

It is clear that different patterns in health-related behavior between men and women constitute a significant proportion of the gender difference in tuberculosis mortality in the Russian Federation. In particular, unhealthy behavior such as harmful drinking is much more prevalent among Russian men than among women, and thus contributes to their vulnerability. The outcomes of the analysis, which suggest a positive effect of per capita alcohol consumption on gender gap in tuberculosis mortality rate, indicate that harmful drinking plays an important role in explaining the gender gap in tuberculosis mortality in Russia. Empirical evidence also indicates that harmful drinking is a major driver in male excess mortality from tuberculosis in Russia.

It is obvious that the reduction in the gender gap in tuberculosis mortality in the 1980s is largely due to the anti-alcohol campaign of Gorbachev. It also might be the case that alcohol is a key factor in explaining the increasing gender gap in tuberculosis mortality in the 1990s. The dramatic grows of alcohol consumption during this period was largely due to increase in the availability and affordability of alcohol after the repealing of the state alcohol monopoly in January 1992 [17]. Compelling evidence also suggests that the strong downward trend in alcohol consumption in Russia could be a major contributor in the recent convergence of tuberculosis mortality among males and females [18].

Here, several potential limitations of this study should be addressed. It might be the case that other factors could also contribute to the gender difference in tuberculosis mortality in Russia. It is plausible that socio-structural factors contributed to an increase in the gender differences in tuberculosis mortality in the 1990s. There is evidence that harmful drinking as a strategy for dealing with psychosocial stress had a detrimental effect on men's health in Russia in this period [19,20]. It is a well-documented fact that Russian men rely heavily on alcohol to cope with stress as a result of the lack of healthier alternative resources for reference [21]. Thus, psychosocial distress, combined with the high availability of alcohol, is believed to be the main contributor to the disadvantage in male tuberculosis mortality in the 1990s.

Other confounding variables, such as smoking, can also affect the gender gap in tuberculosis mortality. Smoking is widely recognized as an important avoidable risk factor for tuberculosis mortality [22]. Research evidence from ecological studies indicates that smoking might explain 33% of the variance in the gender gap in tuberculosis notifications [23]. However, taking into account the fact that smoking has a long-term effect on tuberculosis mortality, this factor alone cannot explain the dynamic of gender gap in tuberculosis mortality in Russian during the past decades.

Finally, we relied on estimated total level of population drinking across the period. However, the accuracy of estimates of actual alcohol consumption level using indirect methods depends significantly on whether the alcohol drinking is the only factor affecting the index chosen as the indicator of alcohol-related outcomes. This is a potential drawback of such methods, because many confounding variables influence the level of alcohol-related outcomes [19].

In conclusion, the results of present study indicate that harmful drinking is the main behavioral driver explaining the cause of high gender differences in the mortality rate from tuberculosis and its dramatic variations in Russia. These findings have important implication for alcohol policy in Russia, suggesting that tuberculosis prevention programs should focus more on solving the problem of alcohol availability.