Social influence research in exercise has highlighted the motivation-boosting potential of working out with an exercise partner or group, but to the authors' knowledge there has been no research to date characterizing the typical dyadic exercise relationship, which is an interpersonal relationship that includes regular co-exercise. If exercise partners are motivational, then characterizing their relationship is important. A sample of 555 undergraduates were administered a survey, 383 of whom met inclusion criteria and reported having or having had an exercise partner. Participants (77%) reported that their exercise relationships typically emerged out of previously existing relationships. Participants reported (on a 1-7 Inclusion of Other in Self Scale) that they were very close with their exercise partners (M = 5.07 + 1.56) and that (out of 10 discussion topic categories) they talked about a number of topics outside of exercise (M = 6.53 + 2.50) and during typical workouts (M = 4.21 + 2.69). Exercise dyadic relationships were characterized by mutual goal facilitation, and participants whose exercise relationships had dissolved or failed reported significantly lower interpersonal closeness, lower communication breadth, and more performance-based goals than participants who reported an ongoing exercise relationship (ps < 0.05). Participants exercised more often the more an exercise relationship was defined by exercise (p < 0.05), suggesting that exercise relationships that revolved around exercise were more immediately productive than exercise relationships that did not prioritize exercise.

Exercise relationships, Gym relationship, Physical activity, Workout buddy

The worldwide population is becoming increasingly inactive and the resultant decreases in health are marked [1,2]. However, one of the most promising solutions to the issue of exercise adherence and effort is social influence [3-5]. Social influence has been cited as a predictor of exercise participation and has been shown to be associated with reduced attrition from exercise programs [6-8]. Dyadic exercise has also been found to have stress-management benefits when compared to exercising alone, such as lowered tension and tiredness, as well as increased calmness and energy [9]. The role of valued others has been emphasized in many of exercise psychology's most ubiquitous theories (e.g., verbal persuasion and vicarious experience in self-efficacy theory, subjective norms and social support in the theory of planned behavior, relatedness in self-determination theory). The inclusion of and focus on the importance of the "other" in exercise and physical activity engagement has made the leap from science to practice, as many popular fitness and health magazines are rife with recommendations and offers such as "grab a partner for a better workout," "7 ways to find a workout partner," or "5 reasons why having a workout partner can help you achieve your goals" [10-12]. However, the qualities of an ideal (or even typical) workout partner relationship have not been empirically investigated, and practical recommendations are speculative, at best. Although there are constructs of the social psychology of exercise that attempt to capture feelings of support from others (i.e., social support), social identity [13] and the fulfillment of an individual's need for relatedness [14] to date there are no investigations of successful exercise friendships [15].

In this paper we examined the nature of exercise relationships through an online survey. An exercise relationship, as defined in this study, is a dyadic interpersonal relationship that is rooted, in some degree, in the exercise context, with the key defining trait being regular co-exercise. Exercise partners are people who exercise with one another and rely on each other in their chosen exercise context (e.g., in the gym, on the track, on the trails, or on the road). Exercise relationships can be stand-alone relationships (e.g., a relationship formed and maintained within the exercise context or purely for exercise-related goals) or they may be nested within a larger relationship (e.g., a lifelong friend, family member, or romantic partner with whom someone has chosen to exercise). The success of the relationship is defined in this study by the relationship viability (i.e., the degree to which the relationship is socially/emotionally nurturing) and the degree to which the relationship is ergogenic.

There are a number of theories examining relationships outside of the exercise context that may be relevant, but have yet to be examined through a kinesiological lens. Accordingly, a review of relationship theory and research is warranted. To begin, we review interpersonal communication theories and constructs that may be relevant to the formation and maintenance of a successful exercise relationship.

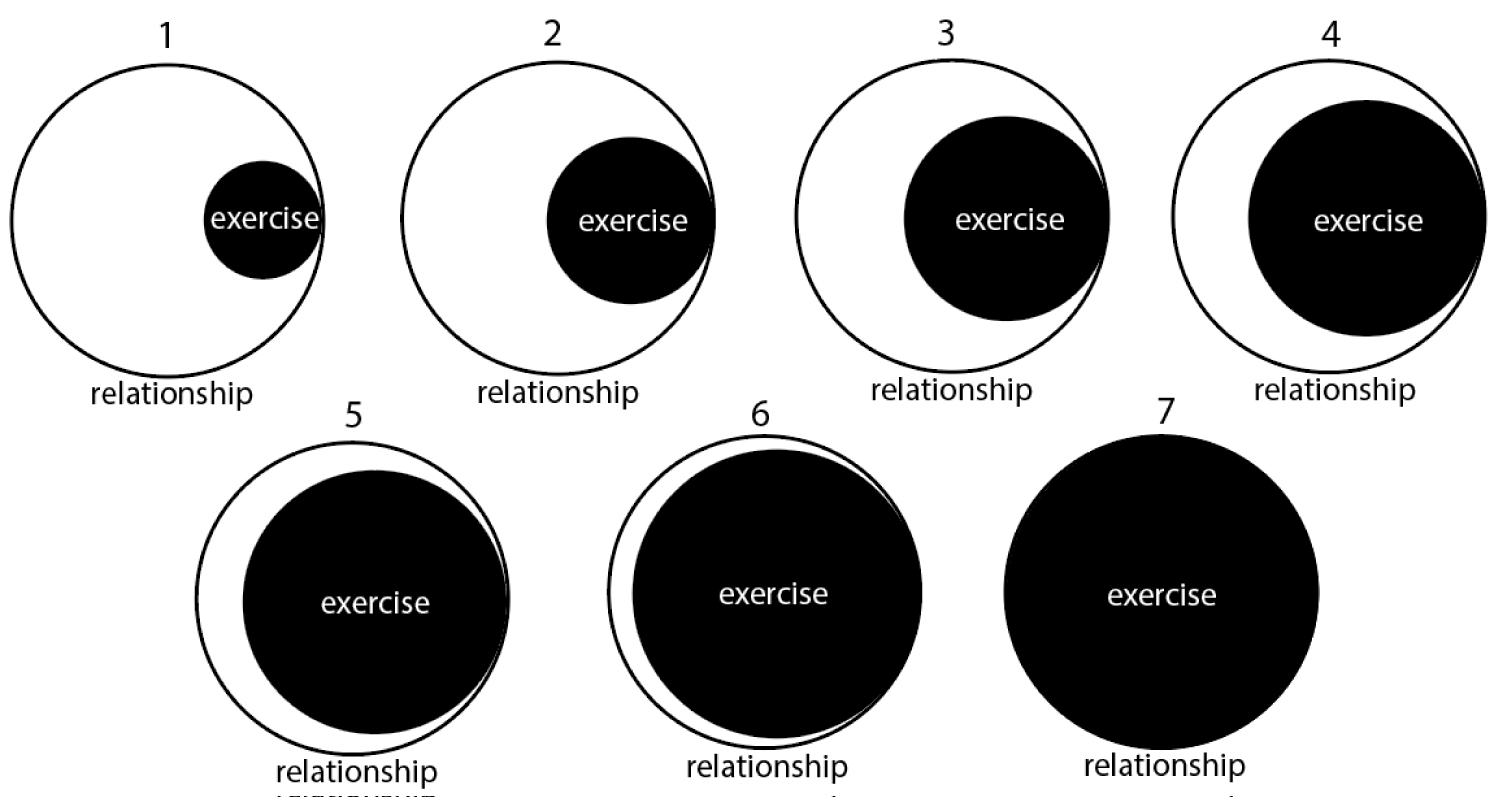

Relationship development involves processing both the quality and utility of the relationship. Little is known about how these relationships develop and flourish in exercising settings, but through the lens of relationship quality and utility, researchers can better understand their role in prompting or hindering physical activity behaviors. We illustrate the conceptualization of exercise relationship development by separating relationship quality and relationship utility as viewed in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Variables related to the development of exercise relationships.

View Figure 1

Figure 1: Variables related to the development of exercise relationships.

View Figure 1

Relationship quality comprises three components: Interpersonal communication, interpersonal closeness, and viability. Interpersonal communication is conceptualized as frequency of communication, breadth of topics, relevance of the communication to the task, and encouragement. Interpersonal closeness is the degree to which individuals in a relationship share an identity. Relationship viability is the time spent together (both acutely and long-term). The combination of these three components are largely responsible for the current understanding of relationship development and growth over a period of time. Although these variables are not a perfect representation of all aspects of relationship quality, they are variables that are core to understanding relationship quality.

Interpersonal information is shared and learned through self-disclosure, a key component of relationship formation. At the most basic level, this sharing of information can be understood through the amount of talk that exercise partners engage in during sessions, the breadth of those discussions, the relative talk that is occurring, and the encouragement that is happening, or not happening, during bouts of exercise together. Self-disclosure is a component of this verbal communication and one that will likely occur during exercise sessions and facilitate the development of exercise relationships. Social penetration theory outlines that as a relationship begins to develop and flourish, the members of the relationship begin to communicate more information and transfer more intimate information to the other member of the dyad [16]. One outcome of the social penetration perspective is that the more time people spend in a relationship, the more likely individuals are to communicate about a wider breadth of topics and self-disclose more personal information [17]. This depth (i.e., sharing fears, intimate details about oneself) is likely to have a relationship to interpersonal closeness, but is a discrete process. For the purpose of this study, we conceptualize communication by the amount of talk during sessions, relative talk, breadth of conversation, and partner encouragement, as these are likely the most relevant components of communication present in exercise relationships.

Closeness is conceptualized as how interconnected an individual perceives they are with another person [18]. When an individual is in a close relationship, they are likely to act and think as if some or all aspects of the partner are in union with their partner [18]. Therefore, if an individual is interconnected with a partner, it is likely to affect their cognitions in a way that will alter behavior. Researchers in social psychology and social cognition have conceived of closeness as the collective aspect of self [18,19]. Due to this perspective on interpersonal closeness, it is worthwhile to measure the self in the collective in a visual representation of the self-overlapping with the other individual in the relationship. Previous research has highlighted that similarities between an individual and a partner stem from a mutual influence and an overlap of traits, beliefs, and schemas [20].

Of critical importance is whether an exercise relationship is sustained or terminated. Relationship viability comprises total relationship length, exercise relationship length, and how often exercise partners hang out with one another. Each of these variables is a measure of time in the relationship – either acutely (as with hangout time per week) or chronically (as with duration of the relationship). These factors, along with interpersonal communication and interpersonal closeness, are likely to covary because all are forms of investment in the relationship, which can improve an individual's likelihood of staying in a relationship [21].

Value can be derived from either the pleasure inherent in the relationship (i.e., positive affect associated with having another person to exercise with) or an auxiliary source such as goal attainment. People are likely to value and seek others who have the ability to facilitate their goals [22]. For example, in an exercise friendship perhaps holding the other person accountable to show up, having them try a new task, pushing them to work harder, or helping a partner embrace a more adaptive achievement goal strategy could be factors that provide utility in the relationship. Physical fitness is seen as a key factor when assessing a hypothetical exercise partner's appeal, and similar fitness abilities and goals are what many prioritize [23,24]. Though exercise partners who initiate their relationship with a goal in mind may value their relationship at the onset that value may decline once goals are achieved [25]. Indeed, relationships involving persons who most easily see relationships in the context of rewards and costs, who are more prone to leave a relationship that is not immediately beneficial to them, tend to have poorer quality relationships [26].

The purpose of this study was to explore the nature of exercise partner relationships by characterizing them on several key features. Most importantly, we sought to examine the exercise relationships from two perspectives: (a) Relationship quality, as inferred through communication, relational closeness, relationship viability, and (b) Relationship utility (i.e., the relationship's ergogenic potential), as inferred through reported exercise goals and behaviors as well as the perceived benefits of working with an exercise partner.

We examined the following research questions:

1. What is the relational background (status, meeting context) of exercise relationships?

2. What is the relational quality (communication, closeness, viability) of exercise relationships?

3. How do communication, closeness, and viability relate to one another in exercise relationships?

4. What are the individual exercise goals and behaviors of those who have/had an exercise relationship?

5. What are the exercise goals and behaviors during exercise with a partner?

After obtaining institutional approval from the Human Research Protection Program, an anonymous web survey hosted by Qualtrics was conducted on undergraduate students enrolled in communication courses at a large Midwestern university. Informed written consent was obtained from the study participants. Participants were recruited and enrolled in the study through the website Experimetrix, which allowed them to obtain course credit while keeping their responses anonymous. The goal was to obtain at least 350 viable participants based on the size of other exercise survey studies of college students [27,28]. Participants who did not have an exercise partner or who did not exercise at all were automatically forwarded to the end of the survey to receive their participation credit.

A total number of 557 students enrolled and consented, though 153 did not meet criteria for inclusion (83 = non-exercisers, 70 = never had an exercise partner) and 21 were excluded (17 = non-completion of survey, 4 = bogus responses). The final remaining sample (N = 383; 199 = females, 182 = males, 2 = unreported) was included for subsequent analyses. The mean age of the sample was 20.09 years (SD = 2.58). The sample was primarily Caucasian (n = 295, 77.0%) and non-Hispanic (n = 317, 82.7%).

The 82-item survey consisted of relational background and quality, participant exercise goals and behaviors (both individual and during exercise with the partner), and basic demographic information and took approximately 30 min to complete. Participants responded individually, not with their exercise partner.

Exercise partner was defined for participants as "a person with whom you exercise or train consistently." The status question was, "Do you have an exercise partner/s?" Response items were (a) "I have never had an exercise partner," (b) "I used to have an exercise partner but I don't anymore," (c) "I have an exercise partner but we haven't exercised together in some time/are taking a break," and (d) "I have an exercise partner. "Participants who reporting having or having had an exercise partner (b, c, or d) were instructed to "focus on one exercise (current or past). If you have multiple exercise partners, choose your primary exercise partner (the one with whom you exercise the most frequently)" for subsequent questions. To determine meeting context, we asked "Did you meet your exercise partner in an exercise context or elsewhere?"

Relational quality contained three dimensions; communication, closeness, and viability. These dimensions were measured with nine different scales.

The amount of talk during typical workouts and most-enjoyable workouts were assessed with a single item soliciting the percentage of workout time spent "talking to each other." Participants used a sliding scale that allowed the selection of options between 0% and 100% in 10% increments. To assess whether participants or their partners tended to dominate the conversation, the respondent's relative talk contribution to intra-workout conversation was assessed with a single 5-point Likert-style item ranging from 1 (mostly you) to 5 (mostly exercise partner).

The content of conversation with the exercise partner outside of workouts, in typical workouts, and in most-enjoyable workouts were assessed with a single check-all, 10-option item listing various discussion topics: Exercise, work, family, friends, romantic relationships, hobbies, current events/news, small talk, philosophy, other. Communication breadth was calculated by summing the number topics checked. A follow-up, open-ended item prompted participants to elaborate on what they talked about within the topic areas they selected.

To measure exercise encouragement, we asked two questions about typical workouts and most-enjoyable workouts: "My exercise partner encourages me when I am struggling," and "I encourage my exercise partner when she/he is struggling." Each was measured on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) scale. The mean of these 2 items was calculated to create a single measure of reciprocal exercise encouragement (α = 0.91).

Closeness was assessed with the 7-point Inclusion of Other in Self (IOS) Scale [18]. The IOS scale uses two circles, one that represents self and the other that represents the other person. The circles start with no shared space (i.e. two separate circles, rating of 1) and gradually start to overlap at each interval until they share the majority of the space between the two circles (rating of 7). This scale has shown acceptable reliability (α = 0.93). The amount of exercise in the relationship was assessed with a single item scale created for this study (hereafter referred to as the Exercise in the Relationship Scale – ERScale), which displayed seven nested circles depicting exercise represented as a progressively greater proportion of the entire relationship (see Figure 2). The image was accompanied by the following prompt: "Please choose the picture that best describes the extent to which your relationship with your exercise partner is rooted in exercise." Scores on both the IOS scale and ERScale ranged from 1 to 7.

Figure 2: Exercise in the relationship scale (ERScale).

View Figure 2

Figure 2: Exercise in the relationship scale (ERScale).

View Figure 2

Viability was measured as relationship length, exercise relationship length, and hangout frequency. Relationship length was measured as the total amount of time the exercise partners had known each other. This single item, "How long have you known your exercise partner?," was followed by open-ended response options soliciting number of months and years. Exercise relationship length was assessed with a single item, "How long have you and your exercise partner been working out together?," followed with open-ended response options soliciting number of months and years. Hangout frequency was measured as the number of days participants saw each other outside of exercise, assessed with a single item, "How many days do you and your exercise partner see each other outside of exercise?"

We measured relational utility in terms of individual exercise goals and behaviors and exercise goals and behaviors with partner to assess whether individual goals and goals with a partner are related and if they are useful to achieving one's goals. We assessed individual exercise goals and behaviors in three ways: Exercise frequency, exercise modality, and exercise goals (including mastery goals). Exercise frequency was assessed with a single item, "how many days per week do you exercise total?" Exercise modality was assessed with a single item, "What type of exercise? [Check all that apply]. "Participants who selected "other" from the list were directed to an open-answer follow-up item to elaborate.

Two additional items to measure mastery goals (i.e., goals that are focused on self-improvement and task mastery) were modeled after those used by Elliot and McGregor [29]. Participants indicated their agreement on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) scale with two questions: "When I exercise, my goal is to perform better than I did during my last workout," and "When I exercise, my goal is to not perform worse than I did during my last workout. "The mean of those two items was calculated to produce an overall mastery goal score.

We assessed exercise goals and behaviors with partner in 5 ways: Exercise frequency with partner, exercise engagement, comparative exercise behavior, performance goals, and goal facilitation. Exercise frequency with partner was measured by asking the number of days that participants exercised with their partner, assessed with the item, "How many days per week, on average, do you and your exercise partner exercise together?"

Exercise engagement was measured with 3 items that assessed looking forward to partnered workouts, exercise persistence with the partner, and likelihood of the exercise partner to reduce exercise attrition. These were assessed with three Likert-type agreement items on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) scale: "I look forward to workouts with my exercise partner," "I exercise harder/longer when I'm with my exercise partner," and "I am likely to skip a workout if my exercise partner is unavailable". These items were not combined due to low internal reliability (α = 0.46).

We used 7 items to ask participants to evaluate themselves relative to their partner on a 1 (much less) to 5 (much more) scale. These comparative exercise behavior questions led with, "Compared to my exercise partner, I am…" and the seven items were: "Physically fit," "motivated in exercise," "likely to lead a workout," "satisfied after a workout," "likely to push or encourage the other during a workout," "likely to suggest ending a workout/reducing the intensity," and "likely to suggest prolonging a workout/increasing the intensity." Negatively worded questions were recoded to match the valence of the positively worded statements for data analysis (α = 0.77).

Two items to measure performance goals (i.e., goals that are focused on comparison of the self with another) were modeled after those used by Elliot and McGregor [29]. Participants indicated their agreement on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) scale with two questions: "When I exercise, my goal is to outperform my partner," "When I exercise, my goal is to not do worse than my partner." The mean of those two items was calculated to produce an overall performance goal score (α = 0.68).

Data analysis involved the use of JASP Version 0.11.1 (JASP, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). A summary of bivariate correlations, means, and standard deviations of key study variables is available in Table 1. Research questions posed in the introduction are examined below.

Table 1: Summary of bivariate correlations, means, and standard deviations of key study variables. View Table 1

For RQ1, in terms of relationship status, most participants reported having a current exercise partner (42.6%), followed by a former exercise partner (34.5%) or an exercise partner who was "on a break" (23.0%). Comparisons between exercisers with different relationship statuses are addressed under RQ7. Regarding meeting context, the overwhelming majority of exercise partner relationships began outside of an exercise context (77.0%). When participants were asked to elaborate on how they met their exercise partner, they commonly referred to the role of their partner as being a family member, significant other, or roommate. In sum, most participants had an exercise partner, and this was someone with whom they had a close relationship outside of exercise.

For RQ2, we assessed relational quality in terms of three dimensions: communication, closeness, and viability. In terms of communication, regarding amount of talk, participants reported spending half of their workout time talking with their partner whether in typical workouts (M = 49%, SD = 22.56) or most-enjoyable workouts (M = 50%, SD = 24.23). Regarding relative talk, participants reported a value significantly higher than the midpoint for communication in typical workouts (i.e., their partner tended to talk more than they did) (M = 3.92, SD = 0.63), t (365) = 27.84, p < 0.001. In most-enjoyable workouts, talk was more equal but still primarily from the participants' partners (M = 3.06 SD = 0.54), t (365) = 2.21, p = 0.027.

A complete list of communication topic frequencies is reported in Table 2 and Table 3. The most frequently reported conversation topics varied only slightly between outside workout and within-workout contexts. Communication breadth was collected for outside workouts, in typical workouts, and in most-enjoyable workouts by summing all communication topics. Participants reported talking about a greater number of topics outside workouts (M = 6.53, SD = 2.50) than in typical workouts (M = 4.21, SD = 2.69), t (382) = 14.82, p < 0.001, or most-enjoyable workouts (M = 4.01, SD = 2.82), t (382) = 15.33, p < 0.001. In addition to conversation, participants reported agreement higher than scale midpoint for reciprocal exercise encouragement (M = 4.04, SD = 0.81), t (382) = 25.10, p < 0.001, in typical workouts.

Table 2: Communication topic frequencies and communication breadth. View Table 2

Table 3: Means and standard deviations of variables by meeting context and relationship status. View Table 3

Participants rated their closeness to their exercise partner higher than the midpoint on the IOS scale (M = 5.07, SD = 1.56), t (381) = 13.44, p < 0.001, and lower than the midpoint on the ERScale (M = 3.02, SD = 1.81), t (381) = -10.58, p < 0.001, suggesting that participants were very close and exercise was only one component of a greater relationship. In terms of viability, the median value for exercise relationship length was 12 months – one third of the median total relationship length (36 months). Participants reported seeing their partner outside of exercise frequently (M = 4.87 days/week, SD = 2.11).

For RQ3, partner closeness was moderately related to communication breadth outside workouts, r (382) = 0.49, p < 0.001, and weakly related to communication breadth in typical workouts, r (382) = 0.21, p < 0.001. A Steiger t-test indicated that the correlation was stronger for outside workouts than typical workouts (z = 4.39, p < 0.001). A similar pattern was seen with ERScale and communication breadth outside workouts, r (382) = -0.31, p < 0.001, typical workouts, r (382) = -0.23, p < 0.001, and most-enjoyable workouts, r (382) = -0.16, p = 0.002, suggesting that closer exercise partners tend to narrow their communication in exercise.

For RQ4, regarding exercise frequency and exercise modality, participants reported exercising often (M = 4.75 days/week, SD = 1.59) and engaged in numerous activities from running to racquetball with running (65%), weightlifting (58%), and walking (56%) as the primary exercise modalities. The exercise goals that were most frequently reported were exercising to improve fitness (M = 4.21, SD = 0.90), feel good (M = 3.95, SD = 1.01), and manage stress (M = 3.93, SD = 1.00).

Mastery goals, which focus on self-improvement were reported significantly higher than the scale midpoint, (M = 4.01, SD = 0.72), t (382) = 26.95, p < 0.001. Mastery goals were associated with exercising for the purpose of enhancing fitness, r (382) = 0.44, p < 0.001, relieving stress, r (382) = 0.39, p < 0.001, to feel good, r (382) = 0.39, p < 0.001, and to have fun, r (382) = 0.31, p < 0.001.

For RQ5, regarding exercise frequency with partner, participants reported exercising with their partner during most of their workouts (M = 2.8 days/week, SD = 1.43). Mean responses to the three exercise engagement items were above the scale midpoints. For the question, "I look forward to exercising with my workout partner," participants reported agreement significantly higher than the scale midpoint (M = 3.90, SD = 0.87), t (382) = 20.26, p < 0.001. They also reported values significantly higher than the scale midpoint in response to statements that they were likely to skip a workout if their partner was absent (M = 3.19, SD = 1.26), t (381) = 2.88, p = 0.005, and their partner helped them to exercise longer and harder (M = 4.01, SD = 1.00), t (382) = 17.78, p < 0.001. Regarding comparative exercise behavior, there was no evidence that participants differed in fitness and motivation when compared to their exercise partners (ps > 0.06).

Despite the abundance of purported benefits of having an exercise partner on physical activity, there is a dearth of research directly examining exercise relationships. The purpose of this study was to explore the nature of exercise partner relationships by characterizing them on several key features in the literature on interpersonal relationships in general. Most importantly, we sought to examine the exercise relationships from 2 perspectives: (a) Relationship quality, as inferred through communication pattern, interpersonal closeness, and vitality and (b) Relationship utility (i.e., the relationship's ergogenic potential), as inferred through reported exercise goals and behaviors as well as the perceived benefits of working with an exercise partner.

Exercise relationships in this sample were characterized by their long length, high interpersonal closeness, robust communication both in and outside of exercise, and their existence within a greater relationship. Unsurprisingly, given the nature of self-disclosure in relationship formation and maintenance, participants with thriving exercise relationships tended to report being closer to and discussing more topics with their exercise partner than participants whose exercise relationships had ended. This finding is consistent with previous literature that has highlighted the role that self-disclosure plays in the development and maintenance of close interpersonal relationships [30]. Participants whose exercise relationships had dissolved reported being significantly less close with their exercise partners and had spent less time together outside of exercise when compared to participants reporting that their exercise relationships persisted.

Talk between exercise partners covers a wide range of topics but becomes more focused during exercise, especially for closer partners. This may be the case because closer partners are more efficient at communicating and, when task-oriented, does not need to say as much to communicate the same message: they are likely better at predicting one another's behaviors and understanding each other's messages than partners who are not as close. Interactions between closer exercise partners are more fluid, allowing them to focus when necessary. These findings, in context of previous research, highlight a unique relationship between relationship quality and components of self-disclosure [30], viability [21], and utility of the relationship [22].

Exercise partners, at least for this sample of college students, typically emerge from pre-existing relationships rather than beginning in an exercise context. Exercise relationships tend to be enduring, close relationships that comprise only a portion of a broader interpersonal relationship. More often than not, exercise is the consequence of an existing connection rather than the basis for a connection initially (i.e., exercise partners are less "workout buddies," and more "buddies who work out"). Exercise partners who met in an exercise context spent less time together outside of exercise but exercised together more frequently and viewed exercise as more important in their relationship when compared to exercise partners who met outside of exercise. Exercise-specific advantages associated with meeting one's exercise partner outside of exercise were offset by relational disadvantages: Meeting in an exercise context was associated with more superficial relationships and lower communication breadth, which could hinder long-term viability. Although there are apparent limitations to relationships that begin in an exercise setting, there is new exciting work focused on helping foster relationships in exercise settings that target adaptive mental health outcomes. Specifically, Law [31] aimed to have first time mothers be physically active with another mother to provide social support and guidance during a difficult life transition. Although there might be drawbacks to assigning an exercise partner, there appear to be some benefits that should be considered in future work. Our findings might be specific to a college-campus population where students live in relatively close quarters and meet each other in classes and resident halls to develop friendships first. They also are a transient population, and while their friendships might endure past their graduation, their ability to exercise together may not be possible. Exercisers who have settled in to work and family life may show a different pattern of how exercise partners emerge.

Communication breadth was positively related to how strongly participants felt about self-improvement and helping their partners, supporting the notion that competition may be a hindrance to self-disclosure and closeness [32]. The most viable exercise partner relationships were cooperative, not competitive, and were seen not as a means to an end but rather an end in themselves.

Though participants occasionally sought an exercise partner to help facilitate their goals, most exercise relationships were less Machiavellian in nature. Exercise partners prioritized self-improvement and wanted to help their partners improve and did not view their partners as competition or a performance benchmark. Despite not obviously seeking out their exercise partners for strategic exercise benefits, participants reported that they found utility in their exercise partner for exercise quality and adherence. Participants whose exercise relationships had dissolved reported being significantly less likely to report having mastery (i.e., self-improvement) goals and reported that their partner had not helped them have more productive exercise sessions when compared to participants with an ongoing exercise partner relationship. This finding is consistent with previous research in sport and exercise psychology that denotes the maladaptive role of lower levels of mastery goals [33].

Exercisers seeking an exercise partner may find that their best option is to turn to a close friend, coworker, romantic partner, or family member to begin an exercise regimen. Exercise partners who are close, comfortable, and open with one another, and can mutually benefit from the relationship are more likely to see fruitful health outcomes than those just looking for someone to motivate them. For individuals merely seeking a "push," a personal trainer or fitness coach may be a better option: Investment may occur through similar transactional processes, albeit monetary instead of emotional/informational.

Exercise partners should focus on getting to know each other, building the relationship outside of exercise as well as in, and viewing exercise time as task to complete rather than a pure social outlet. Approaching workouts with awareness of not only personal goals but also a focus on and prioritization of one's partner's goals may improve relationship quality over time. Our initial findings in this area examine relationship development within the specific domain of physical activity behaviors for optimal outcomes. One timely consideration is the role of exercise friendships when social distancing is needed. Based on these initial findings, exercise friends could still "meet up" in a virtual environment and develop or maintain these friendships when it is not possible to meet in in person. However future research should test how virtual exercise relationships differ from in-person relationships.

As with any research, this study has potential limitations. Firstly, this was a survey design, eliminating the possibility of causal inference and precluding practical recommendations for where to look for an exercise relationship or what qualities the ideal exercise relationship may have. Secondly, relying only on participant feedback may also threaten assumptions of accuracy (e.g., can participants accurately predict an average number of workout days per week?) and truthfulness (e.g., will participants be honest about how much they look forward to workouts with their partner?). Additionally, we used a convenience sample of undergraduate students whose relationships may not reflect those of the broader population. Notably, the sample we surveyed (college students) reported a high level of exercise and most indicated that they had an exercise partner, which seems to conflict with knowledge of exercise habits of the United States. Finally, we only assessed two domains of exercise (i.e., frequency and type). A more comprehensive and validated assessment of physical activity behaviors would have provided richer data on exercise behaviors.

This study was financially supported by a research fellowship from the Michigan State University College of Education.

CH participated in the data analysis, interpretation of the results, and manuscript writing. EM participated in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of results, and manuscript writing. GW participated in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of results and manuscript writing. DF participated in study design, data analysis, interpretation of results and manuscript writing. All authors approve the final version of the manuscript.

No competing interests exist.