Wünderlich syndrome (WS) is a rare condition, in which spontaneous nontraumatic renal hemorrhage occurs into the subcapsular and perirenal spaces and was described for the first time by Bonet in 1700. The etiology of the entity is very diverse, including benign or malign neoplasms, vascular diseases, infectious and inflammatory kidney diseases, and could be combined with some diseases. Clinically the syndrome is characterized by the classic Lenk's triad. We describe a case of WS in a 37-years-old woman with loss of strength in the right superior limb for three months. After admission in the hospital her physical examination showed up pallor, tachycardia and evolved with diffuse abdominal pain. Fallowing all medical conducts the patient do not resist.

Wünderlich syndrome, Retroperitoneal hemorrhage, Computed tomography

Many causes of retroperitoneal hemorrhage have been described. The origin may be caused by any retroperitoneal structure (renal, vascular, pâncreas, adrenal, etc.). Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage (SRH) of non-traumatic originated from renal parenchymal rupture was first described by Bonet in 1700. And in 1856 Carl Wünderlich made the clinical description. The causes vary a lot: benign or malignant tumors, vascular diseases, inflammatory process, cystic ruptura, infectious. These illness can lead to a retroperitoneal hemorrhage or bleeding into urinary tract, which could be a life-threatening. The symptoms may start rapid or stealthy. It is classically associated with symptoms and signals named by Lenk's triad. The appropriate treatment depends the accurate diagnoses made by radiological imaging and clinical information.

A 37-years-old single woman who presented to emergency department with loss of strength in the right superior limb for three months and associated with loss of sensitivity on feet and legs. She was admitted to the hospital for investigation. In her physical examination was pallor, tachycardia, loss of strength in the right arm and loss of the pain sensitivity in legs and feet. Blood pressure: 140 × 100 mmHg. Evolved with diffuse abdominal pain. Lab results: hemoglobin = 6 (admission); hemoglobin = 3 (before being referred to the computed tomography), hematocrit = 28%, leukocytes = 21.610, neutrophil segmented = 59%, eosinophils = 10%, platelets = 898.000, erythrocyte sedimentation rate = 105, creatine phosphokinase = 3.396, C-reactive protein > 100, urea, creatinine and urinalysis without abnormalities. After all medical conducts the patient do not resist. The computed tomography showed following images (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3).

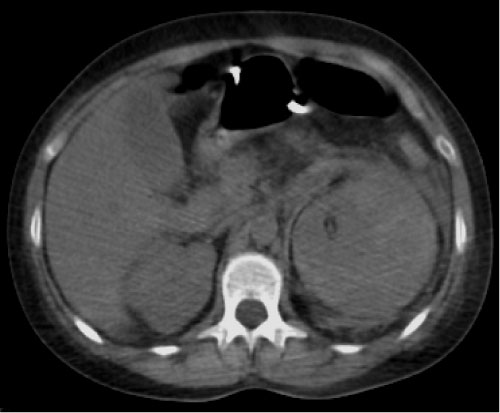

Figure 1: Non-contrast phase. Inflammatory stranding in the left retroperitoneal space. Kidney showing loss contour.

View Figure 1

Figure 1: Non-contrast phase. Inflammatory stranding in the left retroperitoneal space. Kidney showing loss contour.

View Figure 1

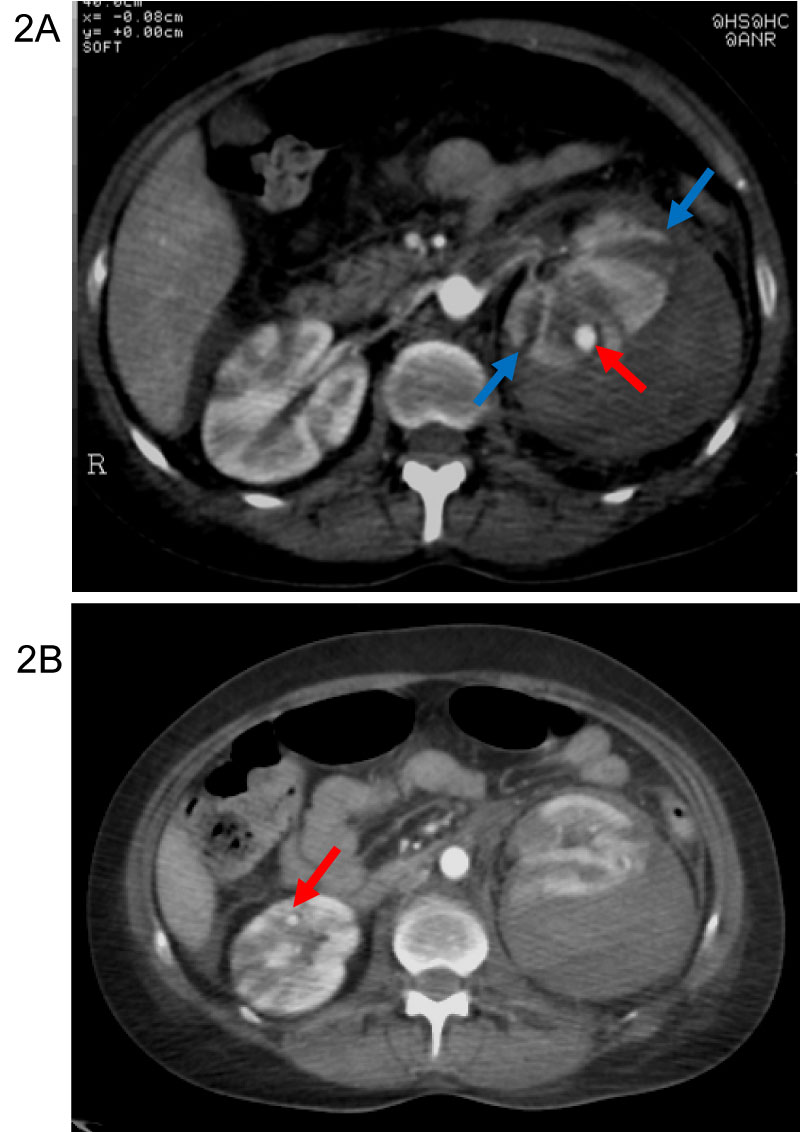

Figure 2: A) Arterial phase. Large hematoma displacing the renal cortex from the capsule (blue arrow). Small aneurysms (red arrow) of small sized arteries in the both kidneys. B) Arterial phase. Striated nephrogram. Small aneurysms (red arrow) of small sized arteries in the both kidneys.

View Figure 2

Figure 2: A) Arterial phase. Large hematoma displacing the renal cortex from the capsule (blue arrow). Small aneurysms (red arrow) of small sized arteries in the both kidneys. B) Arterial phase. Striated nephrogram. Small aneurysms (red arrow) of small sized arteries in the both kidneys.

View Figure 2

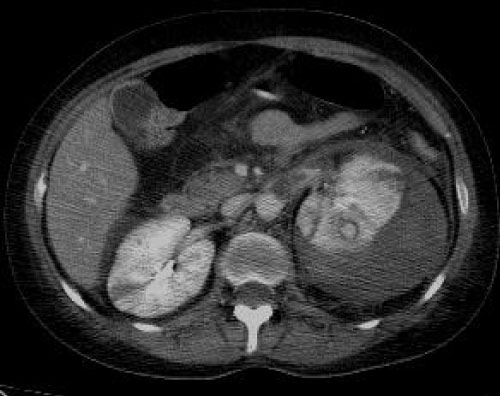

Figure 3: Portal phase. Subcapsular hemorrhage displacing left kidney. Extensive inflammatory stranding is demonstrated in the left peri- and para-renal spaces.

View Figure 3

Figure 3: Portal phase. Subcapsular hemorrhage displacing left kidney. Extensive inflammatory stranding is demonstrated in the left peri- and para-renal spaces.

View Figure 3

Carl Reinhold August Wunderlich, a German physician, in 1856, made the clinical description of SRH of non-traumatic originated from renal parenchymal rupture called by ‘spontaneous renal capsule apoplexy' [1,2].

Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage may have several origins as well as low back pain. The causes could be tumoral, non-tumoral, vascular, inflammatory or systemic (some of these are exposes on Table 1 and Table 2) and [1-11].

Table 1: Causes of spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage. View Table 1

Table 2: Causes of spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage. View Table 2

The most common causes of the WS are renal neoplasms. Angimiolipomas a mesenchymal neoplasm composed by adipose tissue, smooth muscle and dysmorphic blood vessels is the most common cause of the WS. Renal cell carcinoma is in second place and is in first between the malignant tumors that causes WS [3-5,9-13].

Vasculitis has different types and have their classification according to the size and type of vessels involved and the existence or the lack of associated fibrinoid necrosis and/or granulomas [14].

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a rare form of primary systemic vasculitis with heterogeneous presentations. PAN is an autoimmune disease characterized by necrotizing arteritis of small- and medium-sized muscular arteries associated with aneurysmal nodules, condition first described by Adolph Kussmaul and Rudolph Maier in 1866, and could affect multiple organs [15-19].

Most cases of PAN, primary cases, are idiopathic. But several subgroups have already been defined by their aetiologic association, secondary PAN. It is often notice in hepatitis B and hepatitis C infections, malignancies such as hairy cell leukemia, familial mediterranean fever (FMF), connective tissue disease related and deficiency of adenosine deaminase 2 (DADA2) [20-26].

PAN is not associate with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) [20,21,27]. No specific serologic diagnostic tests have been developed.

Renal involvement is common. Some authors plead approximately 60% of patients with PAN have renal involvement. Rarely complicated by acute kidney injury (AKI) in patients with renal involvement, but has high morbidity. PAN is rare in patients with acute abdomen, on the other hand, acute abdomen is frequent in cases of PAN [4,15-19].

The American College of Rheumatology proposed classification criteria for PAN in 1990 [28].

The diagnosis is made by histology in most cases. Imaging studies in vasculitis's are important to determine disease extension and activity. MRI, CT, and CT angiography are the noninvasive techniques to delineate vasculitis lesions.

The clinical picture vary hugely depending on the degree of the bleeding and duration. Acute lumbo-abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, hematuria, hemodynamic instability, anemia and hypovolemic shock may be present [1]. SRH is clinically characterized by the Lenk's triad: Acute flank pain, hemodynamic compromise and flank palpable mass.

WS is not common but is life-threatening entity. SRH is a diagnostically challenging condition and need to be management rapidly and radiological imaging plays an important role in establishing SRH and causes.

Confirmation of the diagnosis by identifying renal hemorrhage in the subcapsular and/or perirenal space, detecting the possible cause and identify any underlying pathological process that may result in a predisposition to hemorrhage for the bleeding is the aim of the imaging in a suspect case of WS [4,29].

Ultrasonography may be the first tool to detect perinephric hematoma, but it has been consider to be only modest useful in identifying renal hemorrhage and in differentiating the renal mass and clotted blood, therefore identification of etiology may not be possible. To document the evolution of hematoma a follow-up with ultrasound is advantageous, because it´s cheap and accessible. Color and spectral Doppler may help in the detection of some vascular and non-vascular pathologies responsible for WS. On US, acute hematoma appears as an isoechoic to hyperechoic collection; subacute and chronic hematomas appear as hypoechoic to anechoic [3,4,12].

Computed tomography (CT) with multiplanar display of datasets allows high-resolution imaging of the renal parenchyma, vasculature, and the collecting system, is the investigative modality of choice in diagnosing WS, its etiology, related complications and severity [1,9,11,30,31]. To demonstration perirenal hemorrhage CT is the method of choice (sensitivity of 100%) but has sensitivity about 57% in identifying renal neoplasm when performed at the time of hemorrhage and may miss rare cases of segmental arterial medio lysis. [1,5,9,12,30] Sequential dynamic contrast image sets should be obtained as corticomedullary, nephrographic and excretory phase images [4]. When CT give few information's it has been suggested that angiography should be done as it can reveal vascular lesions not shown by CT. Renal angiography helps in diagnosing vasculitis, the most common vascular cause of perinephric hemorrhage [5,11,31,32]. If angiography and CT fail because of distortion of renal architecture caused by multiple renal cysts and hypovascularity of some tumors [32], CT could be repeat. Large-volume hematomas could mask hidden neoplasms or the cause of perirenal bleeding remains unclear, therefore follow-up CT is advocate [15,33]. Renal arteriography with selective embolization locates the bleeding site and allows bleeding control avoiding surgery.

If CT failed in initial examination or contrast-enhanced CT is contraindicated, a magnetic resonance (MR) may be performed to reveal the cause of bleeding [3,4,30].

Treatment options depend of the aetiology, the amount of bleeding and how fast the diagnostic are done. Some cases could be follow closely. Minimally invasive procedures as artery embolization is another option. Although, sometimes, nephrectomy could be required.

WS could be a life threatening, and determining its etiology of is often a challenge. Nevertheless, when Lenk´s triad is present the patient should be managed aggressively. Accurate diagnosis order a combination of clinical and radiological imaging information's. All imaging radiological methods have their role. CT, angiography and MR perform an important function in the diagnosis and determine the cause of the syndrome.

Funding: None.

Conflict of Interest: None.

All the authors made substantial contribution to the preparation of this manuscript and approved the final version for submission.